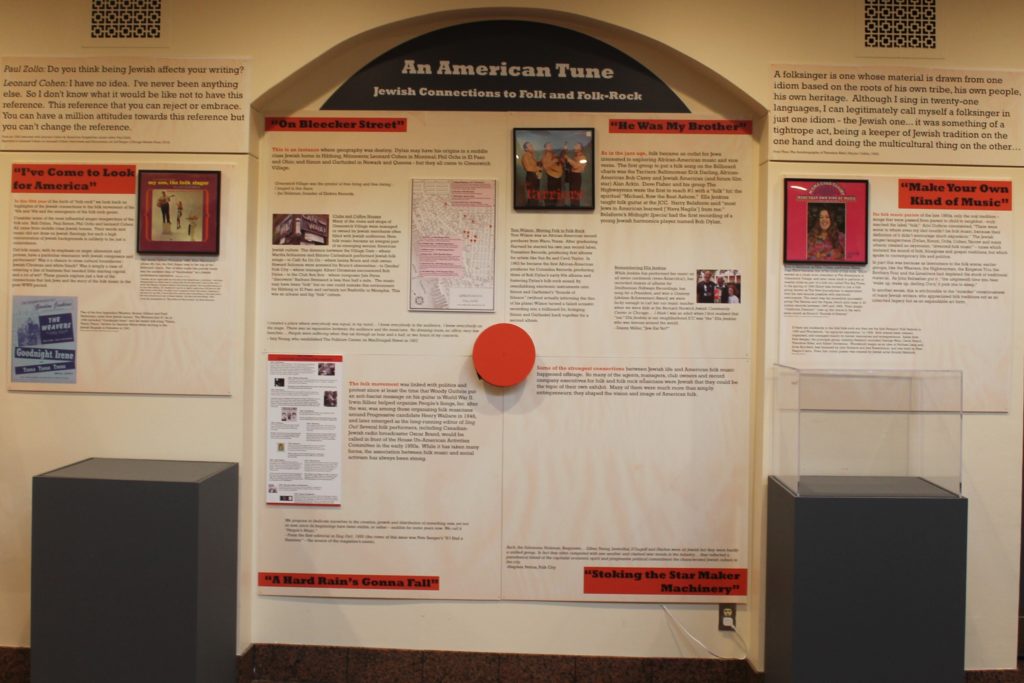

An American Tune: Jewish Connections to Folk and Folk Rock

A JMM Lobby Exhibit on view October 2015 – January 2016

Paul Zollo: Do you think being Jewish affects your writing?

Leonard Cohen: I have no idea. I’ve never been anything else. So I don’t know what it would be like not to have this reference. This reference that you can reject or embrace. You can have a million attitudes towards this reference but you can’t change the reference.

From an 1992 interview with Leonard Cohen by American Songwriter senior editor Paul Zollo. Reprinted in Leonard Cohen on Leonard Cohen: Interviews and Encounters ed. Jeff Burger (Chicago Review Press, 2014)

In this 50th year of the birth of “folk rock” we look back on highlights of the Jewish connections to the folk movement of the 50s and 60s and the emergence of the folk rock genre.

Two weeks before Chanukah 1962, Allan Sherman’s album “My Son, the Folk Singer” rose to the top of the Billboard charts. Part of what made this parody funny was the unlikely idea of “troubador” as a Jewish professional aspiration.

But consider the most influential singer/songwriters of the folk era: Robert Zimmerman (Bob Dylan), Paul Simon, Phil Ochs and Leonard Cohen. All came from middle class Jewish homes. Their words and music did not draw on Jewish theology, but such a high concentration of Jewish backgrounds is unlikely to be just coincidence.

Did folk music, with its emphasis on angst, alienation and protest, have a particular resonance with Jewish composers and performers? Was it a chance to cross cultural boundaries – Jewish/Christian and white/black? Was it simply a case of entering a line of business that needed little starting capital and a lot of wit? Here are five connections that link Jews and the story of the folk genre in the 50s, 60s and 70s.

A Hard Rain’s Going to Fall

The folk movement was linked with politics and protest since at least the time that Woody Guthrie put an anti-fascist message on his guitar in World War II. From the blacklists of the 50s through the Civil Rights, Ban the Bomb, Anti-War, Gay Liberation and Women’s Liberation Movements – Jewish progressive politics and folk music were deeply intertwined. Among the anthems with Jewish authors, “Eve of Destruction”, “I Ain’t a Marching Anymore”, “Blowin’ in the Wind”, “The Great Mandala”, “Scarborough Fair”, and “Alice’s Restaurant”*. *Though he later converted to Catholicism, Arlo Guthrie celebrated his bar mitzvah and his maternal grandmother was a Yiddish songwriter.

On Bleeker Street

This is an instance where geography was destiny. Dylan may have his origins in a middle class Jewish home in Hibbing, MN., Leonard Cohen in Montreal; Phil Ochs in El Paso; and Simon & Garfunkel in Queens – but they all came to Greenwich Village. And Greenwich Village in the 50s and 60s was deeply tied to an emerging culture that was Bohemian with a Jewish accent. The clubs and shops were managed or owned by Jewish merchants, like Izzy Young, and they were filled with Jewish audiences. Between musical acts Jewish comics like Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl performed. The music may have been “folk” but no one could mistake this environment for Hibbing or El Paso and certainly not Nashville or Memphis. This was an urbane and hip “folk” culture.

A Free Man in Paris

Some of the strongest connections between Jewish life and American folk music happened offstage. So many of the agents, managers, club owners and record company executives for folk and folk rock musicians were Jewish that they could be the topic of their own exhibit. Many of them were much more than simply entrepreneurs, they shaped the vision and image of American folk. Here a just a few examples of people who were “stoking the star-making machinery behind the popular song.” > Moe Asch, son of Yiddish novelist Sholem Asch, started his career with an unsuccessful business recording Yiddish music. In 1948 started over by creating the Folkways label, recording Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Peter Seeger and folk traditions from around the globe. > Jac Holzman was an undergrad at St. John’s in Annapolis when he used his bar mitzvah money to establish Elektra Records. Early on he gained the recording contract for Theodore Bikel and blacklisted stars like Oscar Brand and Josh White. He helped establish the career of Judy Collins and later still, the Doors. > David Geffen started in the mail room of the William Morris Agency and later became personal manager to Laura Nyro and Crosby, Stills and Nash. In 1970, Geffen started Asylum Records signing artists like the Eagles, Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell (her 1974 song “A Free Man in Paris” is about Geffen). > The Kingston Trio and Peter, Paul and Mary were groups based on the conceptual visions of music agents Frank Werber and Albert Grossman, respectively.

He Was My Brother

As in the jazz age – folk became an outlet for Jews interested in exploring African-American music and vice versa. The Weavers found success with both the Isreali tune “Tzena, Tzena, Tzena” and later Lead Belly’s “Goodnight Irene.” Dave Fisher and his group The HIghwaymen hit #1 with the spiritual, “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore.” Ella Jenkins taught folk guitar at the JCC. Harry Belafonte is quoted as saying that more Jews learned Hava Nagila from him than from any other source. On his album, Midnight Special, Belafonte also offers a first recording opportunity to a young Jewish harmonica player named Bob Dylan. African-American record producer Tom Wilson decides to put electronic instruments onto Simon and Garfunkel’s Sounds of Silence (without actually informing the duo of his plans). This turned a failed acoustic recording into a billboard hit, making Wilson a midwife to what was called “folk-rock”. Cultural crossings were commonplace throughout this early period of folk.

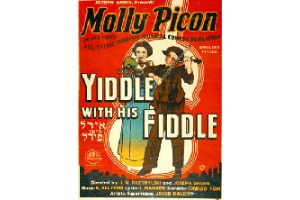

Yiddle with his Fiddle

Of course Jewish life had its own old world folk traditions long before the American folk revival. Klezmer, for example, which originally referred to musical instruments, is a term now applied to the genre of folk music associated with weddings and other celebrations. While it is strongly influenced by Romanian folk traditions it has been widespread in the Ashkenazi Jewish world since the middle ages. The Sephardi have their own ballad traditions. In the late 1950s, singers like Theodore Bikel popularized the use of the guitar, rather than the violin to express Yiddish music. During the folk boom in the 1960s, JCCs in Baltimore and across the nation were bringing Jewish folk music and guitars together on a regular basis.

The height of the movement to bring folk music into the Jewish religious sphere is represented by the work of Debbie Friedman. Best known for her folk version of the prayer for healing “Mi Shebeirach”, Friedman was inspired by secular folk artists like Joan Baez and Peter, Paul and Mary. Her body of work can be heard in a variety of synagogues and cultural centers across the US and Hebrew Union College has named their School of Sacred Music in her honor.

Photo of Exhibit in JMM Lobby

Help support exhibits, programs, and projects like this at the Jewish Museum of Maryland by making a gift online today!

Comments are closed.