“Remember That You Were a Slave”

Article by Avi Y. Decter, former Executive Director at the Jewish Museum of Maryland. Article originally published in Generations 2009-2010: 50th Anniversary Double Issue: The Search for Social Justice.

“Remember that you were a slave” [Deut. 24:22]

Rabbis and Slavery on the Eve of the Civil War

Abraham Lincoln was elected president on November 6, 1860. Within weeks, South Carolina declared that “the union now subsisting between South Carolina and the other States, under the name of the ‘United States of America,’ is hereby dissolved.”[i] The central, critical issue was the future of slavery in America.

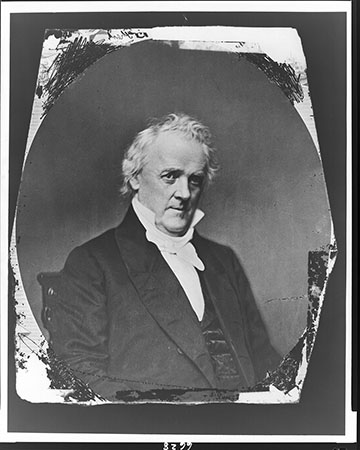

As the crisis of disunion unfolded, President James Buchanan proclaimed a national “day . . . for Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer” to be held on January 4, 1861. On the appointed day, Americans gathered in churches, synagogues, and meeting houses to hear clergy and community leaders reflect on the “present distracted and dangerous condition” of the country.[ii] A number of rabbis spoke that day, espousing views that reflected the diversity of opinion among American Jews and, more broadly, among Americans. Like most Americans at the time, these rabbis tended to take a centrist position on slavery. But there were exceptions at either end of the spectrum, including the rabbis of Maryland’s two oldest congregations.[iii]

Rabbi Bernard Illowy (1812-1871) of Baltimore Hebrew Congregation addressed a solemn assembly at the Lloyd Street Synagogue. A native of Kolin, Bohemia, Rabbi Illowy had attended the rabbinical school in Padua, Italy, and received a Ph.D. at the University of Budapest. In 1848, Rabbi Illowy addressed revolutionary forces passing through Kolin, causing the authorities to bar him from holding rabbinic office. He soon emigrated to the United States, where he was a staunch defender of Orthodoxy and polemicist against Reform Judaism.[iv]

For his Fast Day sermon, Rabbi Illowy chose as his text 2 Kings 4:26: “Peace I want, and peace I am seeking.” He began,

“Our earnest prayer [should be] for the peace and prosperity of our Jerusalem. I say our Jerusalem, for . . . this country will be our Jerusalem. O may it forever continue to be the holy land, the land of liberty, the house of peace, and the asylum of oppressed and persecuted humanity.”[v]

Reflecting on the challenges of maintaining a great republic “like ours, composed of many different nationalities, coming from different countries, differing from each other more or less in customs, manners, habits, languages, creeds, and political views,” Rabbi Illowy pointed to “the contrariety of interests, the principal source from which all dissatisfaction flows . . .”

He then went on to issue a harsh blast against the abolitionist movement:

Who can blame our brethren of the South for seceding from a society whose government can not, or will not, protect the property rights and privileges of a great portion of the Union against the encroachments of a majority misguided by some influential, ambitious aspirants and selfish politicians who, under color of religion and the disguise of philanthropy, have throw the country in to general state of confusion . . .?

Citing instances from the Hebrew Bible in which slavery was tolerated by such revered figures as Abraham, Moses, and Ezra, Rabbi Illowy argued that “these are irrefutable proofs that we have no right to exercise violence against the institutions of other states and countries, even if religious feelings and philanthropic sentiments bid us disapprove of them.” Rabbi Illowy’s talk proved so popular among Jewish secessionists that he was invited to become the spiritual leader of Congregation Shaarei Chased in New Orleans, where he served until 1865.[vi]

Another Orthodox rabbi, Morris Jacob Raphall (1798-1868) of Congregation B’nai Jeshrun in New York City, delivered “what became a highly publicized and disputed statement on the ‘Bible View of Slavery.’” Born in Sweden, Rabbi Raphall spent twenty-four years in England, where he became known for “fighting for the political rights of Jews and against defamations of Judaism.” Raphall was a noted scholar and public speaker. In 1860, he became the first rabbi to give the invocation before the U.S. House of Representatives.[vii]

Rabbi Raphall began his lengthy address by asserting his rabbinical authority, casting himself as the authoritative voice of religion. As he put it, “the question whether slave-holding is a sin before God, is one that belongs to the theologian. I have been requested by prominent citizens of other denominations, that I should on this day examine the Bible view of slavery, as the religious mind of the country requires to be enlightened on the subject.”[viii]

Rabbi Raphall professed himself “no friend to slavery in the abstract, and still less friendly to the practical working of slavery.”[ix] Nevertheless, he insisted that the Bible sanctioned the ownership of slaves. He began by tracing the institution of slavery to the most ancient times preceding Noah. He postulated that Noah’s curse of his son Ham (Gen. 6:25) condemned the African race to servitude, “and to this day it remains a fact which cannot be gainsaid that in his own native home, and generally throughout the world, the unfortunate negro is indeed the meanest of slaves.”[x]

Raphall’s second point was that nowhere in the Hebrew Bible is slavery explicitly condemned as a sin; to the contrary, he argued that the Ten Commandments actually condoned it: “The property in slaves is placed under the same protection as any other species of lawful property, when it is said, ‘Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house, or his field, or his male slave, or his female slave, or his ox, or his ass, or aught that belongeth to thy neighbor.’”[xi] He then unleashed a powerful attack on the abolitionist position, and—pointedly—at Henry Ward Beecher, an abolitionist minister:

In the face of the sanction and protection afforded to slave property in the Ten Commandments—how dare you denounce slaveholding as a sin? . . . What right have you to insult and exasperate thousands of God-fearing, law-abiding citizens, whose moral worth and patriotism, whose purity of conscience and of life, are fully equal to your own?[xii]

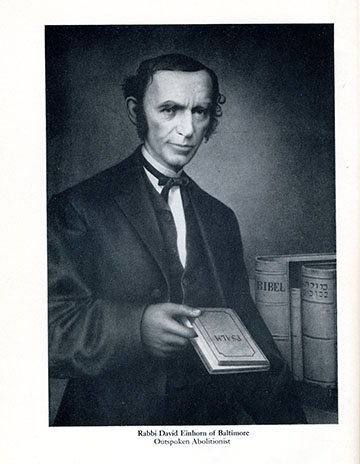

Rabbi Raphall’s talk aroused a storm of protest in the North. Both Jewish and Christian critics attacked him in the newspapers and from their pulpits. Among his most vociferous critics was Rabbi David Einhorn (1809-1879) of Har Sinai Congregation in Baltimore.[xiii]

Rabbi Einhorn, one of the leading Reform rabbis of his generation, was born in Bavaria and studied for the rabbinate at Furth. In 1838, he was chosen as the rabbi at Wellhausen, but was denied the position because of his liberal views. His radical religious position later jeopardized two other appointments, and in 1855 he immigrated to Baltimore to assume the pulpit at Har Sinai. Upon his arrival in America, Einhorn launched an attack on Jewish communal leader Isaac Mayer Wise, who wanted to unite American Jews under an umbrella of moderation that accepted the various streams of American Judaism. Einhorn, in contrast, held out for an uncompromising Reform.[xiv]

Einhorn was equally absolutist in his view of slavery. Within a week of Rabbi Raphall’s Fast Day sermon, he published a blistering rebuttal, charging Raphall with slovenly scholarship, poor logic, false inferences, and unacceptable conclusions.[xv] Although Einhorn recognized that “the moral sense is doubtless subject to all sorts of modifications in accordance with locality, customs, youthful impressions and the times” and conceded that Abraham was a slave-owner, he opened his response in outrage:

The question simply is: Is Slavery a moral evil or not? And it took Dr. Raphall, a Jewish preacher, to concoct the deplorable farce in the name of divine authority, to proclaim the justification, the moral blamelessness of servitude, and to lay down the law to Christian preachers of opposite convictions. The Jew, a descendant of the race that offers daily praises to God for deliverance out of the house of bondage in Egypt, and even today suffers under the yoke of slavery in most places of the old world, crying out to God, undertook to designate slavery as a perfectly sinless institution, sanctioned by God![xvi]

Einhorn went on to argue in detail (and with extensive notes) that Scripture does not favor, approve, justify, or sanction slavery—it “merely tolerates this institution as an evil not to be disregarded.” Indeed, Einhorn wrote, Israel’s fondest hopes center on the idea that “all human beings on the wide globe are entitled to admittance to the service of God.” Citing the book of Job—“Did not He that made me in the womb make [my manservant]? And did not One fashion us in the womb?” (Job 31:15), Einhorn declared: “God created man in His image. This blessing of God ranks higher than the curse of Noah. A book which sets up this principle and at the same time says that all human beings are descended from the same human parents, can never approve of slavery.”[xvii]

Knowing from his own painful experience the consequences of disruption, Einhorn declared that he cherished “no more fervent wish than that God may soon grant us the deeply yearned-for peace.” Still, he argued, “the sanctity of our Law must never be drawn into political controversy, nor disgraced in the interest of this or that political opinion, as it is in this instance, and with such high publicity besides, and in the holy place!” He concluded his passionate response to Rabbi Raphall by saying that Jews must never compromise “the spotless morality of the Mosaic principles . . . for the fleeting wavering favor of the moment.” To do so, Einhorn wrote, would be to expose American Jewry to the charge that “When they are oppressed, they boast of the humanity of their religion; but where they are free, their Rabbis declare slavery to have been sanctioned by God.”[xviii]

Einhorn’s rejoinder to Rabbi Raphall was by no means the only comment that appeared in print. Both Jews and Christians published articles and letters for and against Raphall’s position. Southern newspapers such as the Richmond Daily Dispatch and the Memphis Daily Appeal praised Raphall’s stance; the Charleston Mercury described his sermon as “defend[ing] us in one of the most powerful arguments put forth north or south.” Michael Heilprin, a Jewish scholar sympathetic to the abolitionist cause, called Raphall’s sermon “nonsense” and castigated his “sacrilegious words.” Christian abolitionists arranged for the publication of Dr. Moses Mielziner’s dissertation on “Slavery Among the Ancient Hebrews,” which demonstrated that Jewish views toward slavery in ancient times were distinctly negative.[xix]

Meanwhile, Rabbi Einhorn’s compelling response resulted in threats of mob violence and Einhorn’s flight from Baltimore, never to return to his pulpit at Har Sinai.[xx] He later held pulpits in Philadelphia and New York, where he remained a staunch defender of thoroughgoing Reform.

Unlike the major Christian denominations, whose national organizations had broken apart over the issue of slavery in the decade prior to the Civil War, American Jewry had no national organization or spokesman. Instead, American rabbis’ stance toward slavery and Scripture was based on their personal theological and political leanings.[xxi] Rabbi Raphall’s view of Scripture was grounded in a literal reading of the text and conditioned by his staunch pro-Union politics. Einhorn’s abolitionism and his denunciation of Raphall was of a piece with his Reform theology–he believed that over time, values and meanings change. As he wrote in a letter to a friend, “In all its stages, Judaism shows its capacity for continuous development both as to its form and its spirit, insofar as the latter became ever clearer and purer in the human consciousness.”[xxii]

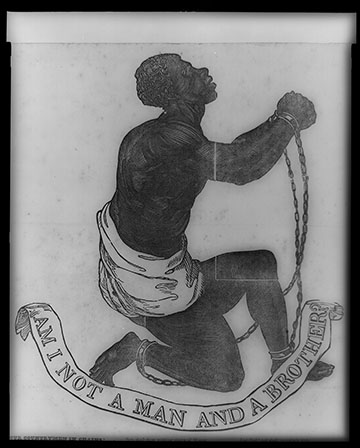

The rabbis’ comments resonated far beyond the relatively small Jewish community. Perhaps the final word may be given to a poem written by a Christian as a rejoinder to Rabbi Raphall, which might well stand as the emblem of our contemporary understanding of the Exodus from Egypt: “He that unto thy fathers freedom gave/Hath he not taught thee pity for the slave?”[xxiii]

Notes

[i] Richard Morris, ed., Encyclopedia of American History (New York: Harper & Row, 1961), 228.

[ii] Presidential Prayer Proclamations, 1841-1865, online at churchvstate.blogspot.com/2010/04/presidential-prayer-proclamations-1841.html.

[iii] Bertram W. Korn, American Jewry and the Civil War (New York: Atheneum, 1970), 15-31.

[iv] I. Harold Sharfman, “Illowy, Bernard,” in Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd ed. (Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2006).

[v] Bernard Illowy, “The Wars of the Lord: Fast Day Sermon at Baltimore, Jan. 4, 1861.” The entire sermon can be seen online at jewish-history.com/Illoway/sermon.html.

[vi] Sharfman, “Illowy,” 726.

[vii] Jack Reimer, “Raphall, Morris Jacob,” in Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd ed. (Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2006).

[viii] Morris J. Raphall, Bible View of Slavery: A discourse Delivered at the Jewish Synagogue, “Bnai Jeshurum,” New York, on the Day of the National Fast (New York: Rudd & Carleton, 1861), 16. The entire address can be seen online at jewish-history.com/civilwar/raphall.html.

[ix] Raphall, Bible, 30.

[x] Raphall, Bible, 23.

[xi] Raphall, Bible, 28f.

[xii] Raphall, Bible, 29f.

[xiii] Korn, American Jewry, 16-20; Reimer, “Raphall,” 97.

[xiv] Sefton B. Temkin, “Einhorn, David,” in Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd ed. (Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2006).

[xv] David Einhorn, “Response,” in Sinai VI, 2-22 (Baltimore, 1861), translated by Mrs. Kaufmann Kohler (Einhorn’s daughter). The full article can be seen online at jewish-history.com/civilwar/einhorn.html.

[xvi] Einhorn, “Response.”

[xvii] Einhorn, “Response.”

[xviii] Einhorn, “Response.”

[xix] Korn, American Jewry, 18f.

[xx] See “The Publisher Departs: The Rabbi as ‘Black Republican,’” Generations 2005-2006.

[xxi] Korn, American Jewry, 15f.

[xxii] Quoted in Temkin, “Einhorn.”

[xxiii] Korn, American Jewry, 248, note 7.