Processions, Debates and Curbstone Encounters Part VII

Article by Avi Y. Decter. Originally published in Generations 2011 – 2012: Jewish Foodways.

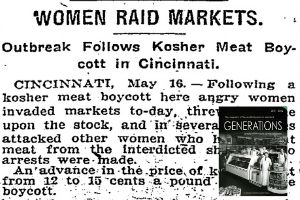

The boycott of 1910 was one dramatic episode in a twenty-year struggle over kosher meat that engaged meat wholesalers, retail butchers, shochets (ritual slaughterers), the Orthodox rabbinate, and thousands of ordinary Jews, especially in East Baltimore. In the first decades of the twentieth century, conflict over kosher meat was a familiar topic. Today, that contestation is little remembered and poorly documented. However, sufficient evidence survives to give us access to the trajectory and meaning of the protracted struggle over kosher meat. Here is that story.

Part VII: A Continuing Struggle

Missed the beginning? Start here.

Despite extensive newspaper coverage of the issues involved, we have no record as to the outcome of the 1910 Kosher Meat War in Baltimore, What we do know is that contention among consumers, retailers, wholesalers, and the rabbinate continued to fester in subsequent years, both in Baltimore and in other Jewish communities.[1]

In May 1918, the retail butchers announced a four-cent a pound rise in prices, effective immediately. Their rationale: rises in the cost of wholesale meat, plus sharp increases in other operating expenses such as ice, wrapping paper, and knife-sharpening. To pressure their customers and to emphasize their determination raise prices, the retail butchers declared a week-long boycott on kosher meat.[2]

The response of Jewish housewives was swift and predictable. They expressed outrage at the “exorbitant price for meat. It is beyond reason, they argued, and we do not propose to make the butchers rich in a little time.” Ten days later, on June 9, the Baltimore Sun reported “Kosher Riots Again.” A thousand women and men demonstrating at the Consolidated Beef and Provision Company, a leading meat wholesaler owned by Wolf Salganik, rushed the plant, leading to the arrests of six women and two men.[3]

The butchers and their customers reached an agreement on a price list that was “said to have the sanction of the wartime U.S. Food Administrator.” But the housewives were indignant that the new prices were for meat with the bone still in, while their understanding was that the price would be for meat with bone cut out. A mass meeting was helo in June 13 and a new meat strike was called. Several labor organizations, including the Amalgamated Garment Workers, the International Ladies Garment Workers, and the Cap Makers, came out in support of the strikers.[4]

The Jewish Comment noted that behind the wholesalers’ decision to raise their prices was a demand from the shochets for increases in their salaries. The wholesale butchers then claimed that this demand forced a rise in price to retailers and, in turn, to consumers. Meanwhile, in a struggle with a struggle, representatives of the Independent Hebrew Butchers Association, representing 150 retail butchers, descended on the store of Asa Goldman, who they alleged was selling meat at prices below those established by the Association, and emptied his refrigerator.[5]

Because America was now a participant in the World War, a new player entered the scene – the Federal Government. The United States Food Administration (USFA) was made responsible for “production, manufacture, procurement, storage, distribution, sale marketing, pledging, financing, and consumption” of foods essential to the war effort. The USFA regulated the supply, distribution, and conservation of foods (for example, promoting “Meatless Mondays”), promising a “fair price” to farmers, while furthering the war effort and preventing food shortages at home.

A hearing was held by the local Federal Food Administrator at which wholesalers, retail butchers, and consumers were able to testify, and an agreement was quickly announced. The agreement established a price list, increased the cost of kosher meat to consumers, and limited the kosher butchers to a profit ceiling of 25 percent. But the resumption of multi-dimensioned hostilities speaks to the importance of the issues and the long complicated struggles that underlay twenty years of contention over a basic – and symbolic – necessity of life.[6]

Continue to Part VIII: Memory and Meaning

Notes:

[1] See, for example, “Kosher Meat Case in Court,” Baltimore Sun, 4 June 1911, p. 9 and “To Boykott Kosher Shops,” Baltimore Sun, 26 February 1917, p. 2.

[2] “Kosher Meat Higher,” Baltimore Sun, 29 May 1918, p. 14.

[3] “Kosher Riots Again,” Baltimore Sum, 9 June 1918, p. 16. “Fined for Kosher Meat Riot,” Baltimore Sun, 10 June 1918, p. 5.

[4] “Kosher Again in Limelight,” Baltimore Sun, 14 June 1918, p. 16.

[5] “Baltimore Jews Abstain From Meat,” Jewish Comment, 14 June 1918, p. 263. “Kosher Butcher Acquitted,” Baltimore Sun, 20 June 1918, p. 16.

[6] “Agreement on Kosher Meat,” Baltimore Sun, 13 June 1918 p. 16. “Baltimore Jews Abstain From Meat.”

2 replies on “Processions, Debates and Curbstone Encounters Part VII”

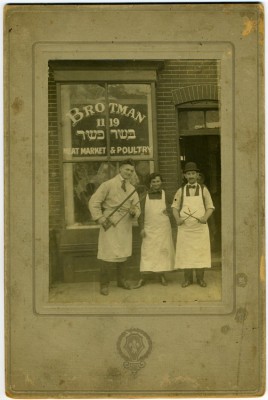

The unidentified man on the left side of the photo in front of Brotman’s butcher shop is my cousin Harry Danoff. This photo was recently posted on our private family FB page. Harry’s Uncle, my grandfather Hyman Danoff also had a kosher butcher store in East Baltimore, probably not too far from Brotman’s.

Thanks so much Leslie! We’ve been wondering who is in this photo for forever – it’s one of our favorites.