A “Children’s Playground” and “Centre for Adults” Part III

Article by Jennifer Vess. Originally published in Generations 2009-2010: 50th Anniversary Double Issue: The Search for Social Justice.

Part III: Not Only a Children’s Playground

Missed part 1 & 2? Start from the Beginning.

The “Jewishness” of the JEA, while not a common element of the settlement house movement, did not conflict with the more typical settlement house activities that took place there. The JEA, like other settlement houses, split its attention between children and adults, though children probably made up the largest number of visitors and enjoyed the most programs. Still the board of the JEA was adamant that “This House is not only a children’s playground, but a centre for adults.”[1] Programs, lectures, and classes aimed at adults addressed many of the issues dear to the hearts of reformers of the day – health and sanitation, culture, and citizenship.

Bettering the health of the poor included improving diet, improving hygiene, and improving sex education. Many settlement houses offered access to health care and settlement workers strove to instruct residents on the latest scientific methods for maintaining good health. The JEA gave rooms to organizations such as the Babies’ Milk Fund Association, the Instructive Visiting Nurse Association, the Health Department Nurses, a Babies’ Clinic, and the Council Milk and Ice Fund. Families took their children to the clinic at the JEA for check-ups and shots, and benefited from organizations that distributed milk and other nutritional foods. These organizations instructed families on such topics as how to eat better and prevent illness.[2] And what they didn’t teach, the JEA would.

For the settlement house workers of the early twentieth century, issues of health were informed by science. What people learned from their parents was not as important as what science could teach. Settlement house workers introduced new ideas on cooking and nutrition, such as the JEA’s Dietetics classes offered to the Mothers’ Club. Scientific education also included introducing topics that had been considered inappropriate for public discussion, such as Social Hygiene – essentially, sex education. While much of the Social Hygiene movement focused on eradicating prostitution, classes and lectures also discussed the biology of the body and sexually transmitted diseases. In 1909 the JEA held a class on Social Hygiene, in 1916 they offered a class on “sex hygiene,” and five years later they gave space to the Maryland Social Hygiene Society.[3]

Along with improving health, JEA workers also hoped to improve the mind. Like other settlement houses, the JEA offered opportunities for neighborhood residents to enrich themselves intellectually and culturally. Practical trade classes (stenography, sewing, salesmanship, bookkeeping) taught young people and new immigrants skills for gaining employment. But settlement house workers, often college-educated men and women, also promoted self-improvement for its own sake. They shared their liberal arts education through lectures and introduced art, music, and history to the immigrant neighborhood.[4]

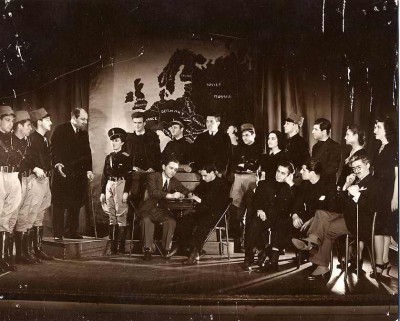

The JEA offered a constant stream of lectures and concerts and in its later years the Baltimore Museum of Art even opened a branch at the JEA for art exhibitions.[5] It also engaged its neighbors in creating music, theater, and art. The JEA Orchestra, made up of children and adults, began in 1917 with twenty-seven members and grew to be an eighty-eight piece ensemble known beyond the walls of the JEA. According to the daughter of its longtime orchestra leader, “It was considered the best nonprofessional . . . symphony orchestra on the East Coast.”[6] The JEA also sponsored the Alliance Players, an amateur performance group that became very popular over the years. In addition, the JEA’s visitors were encouraged to learn on their own. Its reading room contained books for adults and children, and the JEA also supported the presence of the Enoch Pratt Free Library in the neighborhood.

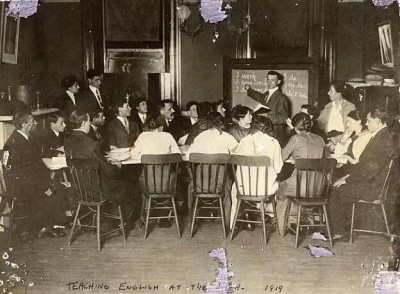

One of the most important goals of any early twentieth century settlement house was the Americanization of recent immigrants. “Americanization” was a catch word of the day that embraced the teaching of the English language, American history, civics, and more. Settlement workers saw Americanization as the best way to address the problem of a diverse society – by creating coherence through assimilation. Achieving citizenship was the logical step for immigrants, and settlement house workers wasted no time in starting new arrivals on the process of becoming “naturalized.” The first head workers of the JEA, Max and Rosa Carton, set about forming citizenship classes within a year of the organization’s establishment.[7]

Many reformers believed that the government – in the form of the public schools – should take responsibility for running citizenship classes, but the city did not assume that responsibility for many years. The JEA offered Americanization programs, English classes, and at one point an Alliance Summer School for Foreigners, which gained the attention of John W. Lewis, the State Supervisor of Americanization.[8] These activities lasted as long as the constituency reflected a recent immigrant community. Over time, however, the push for Americanization decreased as older immigrants adapted to their new country and new restrictive federal laws curbed the influx of immigrants.

Continue to Part IV: The Infant is Safe

Notes:

[1] January 1921 report, JEA meeting minutes, MS 170, Folder 213.

[2] January 1921 report and March 1920 reports, JEA meeting minutes, MS 170, Folder 213.

[3] “Jewish Educational Alliance,” Jewish Comment, December 17, 1909; Aaronson, “Jewish Charities: A Settlement Diary;” January 1921 report, JEA meeting minutes, MS 170, Folder 213. On the Social Hygiene movement, see Social Hygiene 7 (Menasha, Wis.: American Social Hygiene Association, 1921): 139-165.

[4] Davis, Spearheads for Reform, 40.

[5] BMA Art News (October 1943): 1.

[6] Blanche Klasmer Cohen, “Benjamin Klasmer’s Contribution to Baltimore’s Musical History,” Maryland Historical Magazine 72, No. 2 (Summer 1977): 274.

[7] JEA meeting minutes, October 31, 1910, MS 170, Folder 212.

[8] JEA meeting minutes, February 7, 1911; JEA director’s report, October 6, 1921, MS 170, Folders 212 and 213.