A Heady Brew: Magna Carta, Whiskey and Jewish History

A blog post by Museum Director Marvin Pinkert. To read more posts from Marvin click HERE.

I know that everyone has today marked on their calendars as a birthday – probably not your birthday – but the birthday of Magna Carta. It turns 800 years old today. Now the reason it’s on my calendar is that for 11 years I was the steward of the only extant copy of Magna Carta in North America – the copy on display at the National Archives.

Next Sunday I will be offering a free tour of the National Archives at 2pm as part of our Schnapps with Pops program. We are headed to the “Spirited Republic” exhibit – the latest changing exhibit at the National Archives and the inspiration for our JMM program. But given this important birthday, we’ll also be taking a side trip to see Magna Carta.

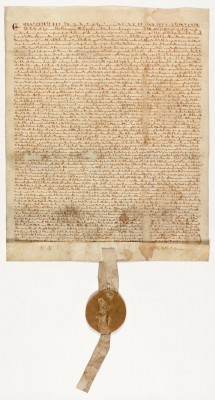

Magna Carta on display at the National Archives is in fact just 718 years old. It was not signed or sealed by King John but rather by his grandson King Edward I. So what makes it special? Well, Magna Carta (Archives trivia – never supposed to write “the” Magna Carta, because it is a Latin name and bears no article) was not a singular act. John put his seal on Magna Carta under threat at Runnymede and from the time the ink dried, John and his successors looked for ways to annul, rescind and evade it. In this long series of royal pledges and revocations – the 1297 Magna Carta stands out because Edward agreed to an additional clause that enrolled Magna Carta in the statutes of England, settling the question of whether this was the permanent law of the land.

And the Jewish connection? Ask yourself “why did the kings keep issuing Magna Carta if they had little interest in conceding absolute royal power?” The fundamental answer is that they needed money and agreeing to a power-sharing formula with the barons was a way to stimulate their assent to new taxes. The original strategy of the Norman kings to finance their rule of their new Anglo-Saxon domain was to bring over Jewish merchants. In addition to developing the English economy, Jews were trusted agents of the monarchy – since their very presence in the country was at the sufferance of the king, the Norman rulers could count on their loyalty.

This helps explain Clause 10 in the 1215 Magna Carta. It is a clause which relieves the baronial families of having to pay interest to Jews after the death of a baron. Limiting the financial dealings of England’s Jews was seen as part of curbing the powers of the king.

When we put Magna Carta back on display in 2011, several reporters asked me if the absence of Clause 10 in the 1297 Magna Carta was indicative of a change in attitude towards Jews. The answer was unfortunately, “no”, the clause is missing from this Magna Carta, because Edward saw fit to expel all Jews from the country in 1290 and therefore could not agree to regulate a trade that – at least on paper – had ceased to exist.

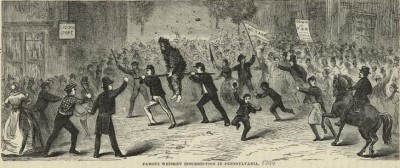

And what about the whiskey connection? Well, “Spirited Republic” is dedicated to the story of the federal government and alcohol, and most of that story is about how the federal government would support itself. The very first American insurrection, more than 60 years before the Civil War, is the Whiskey Rebellion – a pitched battle over the tax on alcohol. In the post-Civil War era, as much as 40% of the federal government’s income rested on liquor excise taxes. This is why the advocates of prohibition helped push through the 16th amendment establishing an income tax before advancing the 18th amendment banning the sale of alcohol. The exhibit contains several documents from Jewish distillers before, during and after prohibition.

So I could frame the connections between Magna Carta, whiskey and Jewish history as being all about the struggle for human liberty… or we could agree that it is all about one of life’s two certainties – taxes.

If you are interested in taking Sunday’s tour, it is free but you must RSVP to Trillion (tattwood@jewishmuseummd.org) by Wednesday so that we can give the National Archives a final count on attendance.