An American in Palestine 5

Mendes I. Cohen Tours the Holy Land Part V: From the River Jordan to the Sinai Desert

Written by Dr. Deb Weiner. Originally published in Generations 2007-2008: Maryland and Israel.

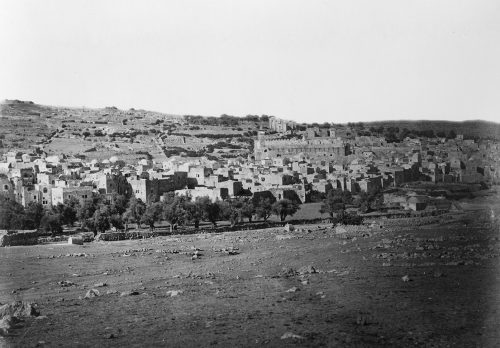

Cohen also encountered Jewish communities outside of Jerusalem during his two trips through the region. “In Palestine there are several cities of Jews,” he explained. “Indeed nearly all the towns contain [at least] a few.” They proved to be even poorer than their counterparts in Jerusalem. He observed Succot with the Jewish community in Nablus (the biblical Shechem), “but as they have found me out to be a rich man I have been constrained to shorten my visit.” Traveling to Hebron, he passed through a town where “All the Yehoodim of the place [heard that] a Frank Yehoodah was coming that way and as their whole and sole object was to get a little cash from me I disappointed them.”[i]

Hebron had a population of 5,000, mostly Arabs, with around 300 Jews (“including 15 she-nar-zim or Tych who are Muscovites.”) Cohen went there to see Judaism’s second holiest site (after the Temple Mount), the Cave of Machpelah, burial place of the biblical patriarchs and matriarchs. That Jews were forbidden to enter the mosque that stood on the site did not deter him, though “the first day I arrived the Yehoodim followed me so closely I could not get a chance to ask permission to see the interior.” The next day he bribed an attendant and went in.[ii]

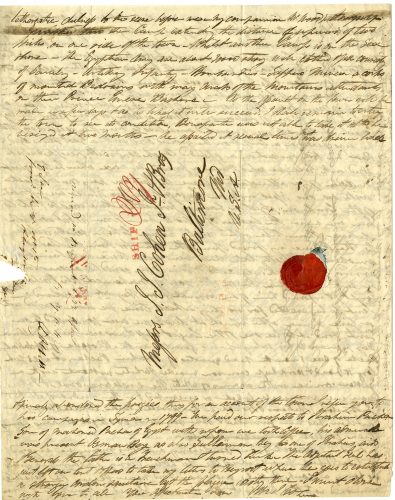

Cohen’s disregard for obstacles of any kind proved to be a hallmark of his trip. Palestine was not a particularly safe place for tourists, especially in areas affected by the war between Ibrahim Pasha and local minions of the Sultan. Cohen described some of the dangers to his mother, but reassured her that “I had my pistols with me.” When he was told that an excursion with some companions by horseback from Jerusalem to the River Jordan would be extremely hazardous, he secured a heavily-armed guard from the Governor of Jerusalem. “We are eight in number all well armed and have an escort of 15 soldiers with an Arab chief to accompany us whom the Governor sent for, persons going on this pilgrimage generally have much to fear from the Arabs . . . looking daily for prey of robbery or plunder.”[iii]

In this case, however, he fell victim to a different kind of danger: like the pilgrims he had previously observed, he was being fleeced. Five days later he wrote in disgust, “A few women gathering herbs were all that we saw out of the reach of what may be called civilization. . . . I considered the whole thing as a farce and got up by the Governor for the purpose of saving his own pocket which by our not employing these Bedouins he would have to provide for himself.” The group’s protectors were “poor miserable almost naked and starved paysans . . . some of them appeared not more than 15 to 17 years of age. . . . [They] had nothing to eat but what we could give them. From the rice we made a pilaff. Our stock of bread was small and as we did not know how many days we should be out had to put it under a rigid guard otherwise in a few moments nothing would have been left.” He concluded, “All travellers speak of the excursion as a perilous one, I would have no objection to go alone on it.”[iv]

But the places he visited were worth the aggravation. After stopping at Jericho and the Well of Elijah, the group reached the Jordan and crossed over its shallow waters. “I cut myself a good cane from one of the many trees that grow on this ‘other side of Jordan.’ From the bed of the river I took stones to serve as a memorial that my children may know that Israel came over this Jordan on ground. I also measured the width of the river where I crossed and found it to be 116 feet English measurement. The deepest part not being more than 4 feet 6 inches. While there is a bank on one side there is none on the other and is evident when ‘Jordan overflows [its] banks at the time of harvest’ that it spreads its benefits over the land.”[v]

From there it was on to the Dead Sea. The guards “endeavored to alarm us for the purpose of hastening us on by telling us the Bedouins would appear in a few moments from their secret places and attack us. But we were not to be intimidated so easy. When we had completed our observations, we mounted our horses proceeding south. . . . Before leaving this very interesting spot I looked in vain to designate the ‘mountains of Nebo to the top of Pisgah that is over against Jericho’ for which I refer you to the 34th or last chapter of Deuteronomy.” Crossing the plain between the Jordan and the Dead Sea, “The feet of our horses sank two or three inches beneath an encrusted surface of soil not unlike snow when frozen on the surface.” He speculated that this phenomenon could be due to the effect of the overflowing Jordan, or proximity to the “salt sea.” Their experience of the Dead Sea—unlike the journey that got them there—would be familiar to modern-day tourists. “Taking off our boots we went some distance into it for the purpose of filling a bottle.”[vi]

On their return to Jerusalem the group stopped off at Bethlehem and Rachel’s Tomb. “We entered within the outer wall of the tomb to see the tomb itself which is nothing remarkable,” reported Cohen. But it did give him a chance to express his solidarity with the Jewish people. “The names of thousands of the Yehoodim are inscribed on its walls to which I added mine in Hebrew.” At Bethlehem he joined his Christian companions in touring a different kind of holy site. “We delivered a letter to the Superior and after partaking of a dinner we were accompanied through the various places sanctified to their religion by the nativity of its founder. St. Matthew Chap 2-24.”[vii]

Cohen’s passage through the Sinai Desert exemplified his determination to pursue his adventures regardless of the difficulties involved. He arranged the projected nine-day trip while in Cairo after his Nile excursion. After securing the necessary diplomatic permissions, he hired a Bedouin sheik as guide, agreeing to pay 600 piastres: 300 down and 300 at the end of the trip, “with a promise of a good back-sheesh (or present) if the journey is made a good one.” The sheik “promises everything with his supply of men. . . . He is to conduct me to Suez, to the top of Mt. Sinai and thence the direct road to Gaza, to point out to me the celebrated places and antiquities on the route. Thus with a perfect understanding my Bedouin sheikh (head of village) came up with his four camels to the gates of the Frank convent” in Cairo where he was staying, “and in the afternoon of the 24th of August I left Cairo.” The four camels were for Cohen, his servant, his luggage, and his water.[viii]

The first challenge was learning how to ride the camel, “which was awkward enough at the beginning but 2 and a half days journey has reconciled me to the mode as well as the utility,” he wrote en route. More worryingly, “Our drinking water does not keep as well as we had expected. . . . However we have undertaken the journey and must submit to its many inconveniences.” When his caravan reached the Well of Moses, he observed the water “gurgling from the ground” with more than the usual tourist’s interest. Unfortunately he “tasted of it and found it to be brackish. The camels did not drink very freely of it.” That night, he recorded in his diary, “the wind blew strong and our tent came down. All hands employed in getting it up.” The next day he jotted, “The sun intensely hot.”[ix]

The “perfect understanding” between Cohen and the sheik did not last long. As he wrote in his diary, “I had much difficulty with him having to dismount from my camel and punch him, knocking off his turban.” In a letter to his mother, he explained, “My sheikh objected to my going to Yor the ancient Elim. Had a quarrel with him. Reminded him of his fair promises, gave him a rap on his head. He found me determined and finally consented good humoredly to go, provided I would not take my luggage, terms agreed upon ‘for his pleasure’ I told him.” With this compromise, Cohen and the sheikh went alone on their detour, to meet up with the rest of their party (and luggage) at Mt. Sinai. Later the two would disagree over other issues, and Cohen ended up hauling the sheik before authorities in Gaza and getting his fee reduced.[x]

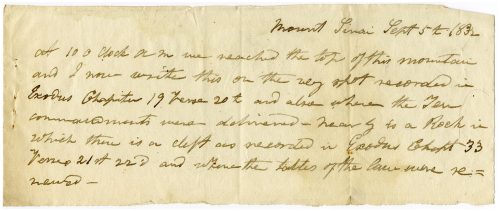

Yet his diary throughout his Sinai trip reveals a palpable sense of biblical history that made the hardships worthwhile. One day he recorded, “The Arabs say that Moses and his army crossed the Red Sea not far from this spot.” A few days later he stayed at a monastery “on the spot they say where Moses was herding his flock when the Lord appeared to him in the midst of a flaming bush.” When he reached Mt. Sinai he ticked off the sites that he came upon in quick succession: “Spot where tables of the law were thrown from the hands of Moses. Spot where the Molten Calf was made. Spot where the Tabernacle was set up. Spot of the Burning Bush. The Well from which Moses fed Jethro’s flock.” The ascent up the mountain took three hours, the descent two. Crossing a wide expanse the following day, he wrote, “I have no doubt the children of Israel passed over this plain. It is one which will contain several millions of people.”[xi]

Continue to Part 6: The Legacy of Mendes Cohen

[i] Letters to Judith Cohen, March 19 and October 2, 1832.

[ii] Letter to Judith Cohen, October 2.

[iii] Letters to Judith Cohen, October 2, March 19.

[iv] Letter to Judith Cohen, March 24.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Letter to Judith Cohen, September 27. As intrepid a traveler as Cohen was, he was outdone by one of his traveling companions, as he admiringly told his mother in his letter of August 27, 1832: “Mr. Lenant, a French traveller in the true meaning of the word [has] been in these parts travelling fifteen years and has become one of the head men of a tribe of Bedouins.”

[ix] Letter to Judith Cohen, August 27; travel notes.

[x] Letter to Judith Cohen, September 27; travel notes.

[xi] Travel notes.