Ask Our Docents: A Blog Series Part V

When leading a tour, each volunteer docent incorporates their own personal memories, experiences, and expertise into the stories they share with visitors. A great example of this is Docent Helene’s response in last month’s Ask Our Docents blog when she shared her personal experience visiting a mikvah for the first time.

For this month’s Ask Our Docents blog, we are thrilled to share another personal memory from a volunteer. This story comes from retired JMM Volunteer Josef Rosenblatt about his first experience of the Lloyd Street Synagogue.

A special thanks to Josef. You can also check out previous Ask Our Docent blog posts or explore other stories from volunteers.

Paige Woodhouse, Project Manager

In the early 1960’s, while in college, I worked for the Baltimore News American as a police reporter. My editors knew of my interest in architectural history and so assigned me to interview Wilbur Hunter, the director of the Peale Museum, about his rescue of the Lloyd Street Synagogue from being lost to history and being turned into a parking lot.

On a hot summer day, I met Mr. Hunter at the Lloyd Street Synagogue. We went into the building with the aid of flashlights because there was no working electricity on the premises. Mr. Hunter said that the surviving members of the Shomrei Mishmeres Congregation were adamant in refusing to sell the building back to the Baltimore Hebrew Congregation because Baltimore Hebrew, in the 1870’s, had sold the structure to the St. John the Baptist Roman Catholic Church. When Mr. Hunter realized the potential destruction of this historic site, he alerted various Jewish leaders, including my father, Rabbi Samuel Rosenblatt, to the danger to the building. The issue was resolved by turning the building into a museum, and in not using it for regular religious services.

By flashlight, Mr. Hunter pointed out that the eastern 30 feet of the structure was separating from the original western portion. The tattered ceiling paintings were visible during my tour of the sanctuary, as were the matzo oven and the mikvah in the basement.

As a result of my interview of Mr. Hunter about the Lloyd Street Synagogue, I wrote an article which appeared in the News American. Fifty years later, I served as a docent at the Jewish Museum, mindful of the near demise of the structure some fifty years before, but for the efforts of Wilbur Hunter.

JMM’s Director of Collections and Exhibits Joanna Church was happy to share Josef Rosenblatt’s original article from the Baltimore American which was published on Sunday, October 20th, 1963. Please see a transcript of the image below.

Transcript:

4B – Baltimore American Sunday, Oct.20, 1963

Synagogue Here to Become Museum of Jewry

By Josef Rosenblatt

What is the value of a 118-year-old building whose basement floors are warped by years of contact with the damp earth, whose windows are broken by vandals, and whose white paint has grown dingy with age?

To a group of Baltimore civic leaders such a building was wort the $75,000 raised to buy and restore the Lloyd St. Synagogue in East Baltimore.

The Jewish Historical Society of Maryland recently bought the structure from the few remaining members of the last congregation to use to synagogue for prayer, the Shomrai Mishmeret.

Future plans call for the restoration and conversion o the fifth oldest synagogue in this country and the third oldest extant Jewish house of worship, into a museum of Jewish art treasures and historical records.

The synagogue changed hands three times before it came to the possession of the local historical group. From its dedication in 1845 until 1889 the building was used by the Nidchei Israel, which is now the Baltimore Hebrew Congregation.

In 1889 the synagogue became a Catholic church as the German Jewish population moved away and was replaced by Bohemian Catholics. In 1895 the building changed hands again as Russian Jewish immigrants moved into the neighborhood.

The Revival style building was “discovered” as an historical treasure by Dr. Wilbur H. Hunter Jr. of the Peale Museum, who since 1953 has been researching Baltimore’s architectural history in conjunction with the Library of Congress, the National Park Service, and the American Institute of Architects.

In 1960 Dr. Hunter spoke to the Baltimore Hebrew Congregation and interested the parishioners in their former home.

A problem exists, according to Dr. Hunter, in choosing the era to which the synagogue should be restored or stabilized.

In 1860, fifteen years after the construction of the house of worship, a thirty foot addition was made to the east end of the building.

Today long cracks reveal where the addition was mated to the original structure, and it might be easier and cheaper, to concluded, to remove the new section, which is pulling away from the rest of the building, than to repair it.

While there are not great differences of style from 1845 to 1860, the later additions which changed the position of the Bima or pulpit presents a problem.

Among the interesting features of the Lloyd Street Synagogue is the stained glass window over the ark which embodied for the first time, the Star of David.

Also the pews has small doors to keep the drafty cold air off the parishioners feet in the unheated sanctuary; above the main sanctuary was a gallery for women which originally had a lattice-work screen around the balustrade.

As the community’s first Jewish house of worship the synagogue contained two ritual baths or mikvot, a religious school on the ground floor, and an oven for baking the Passover matzos.

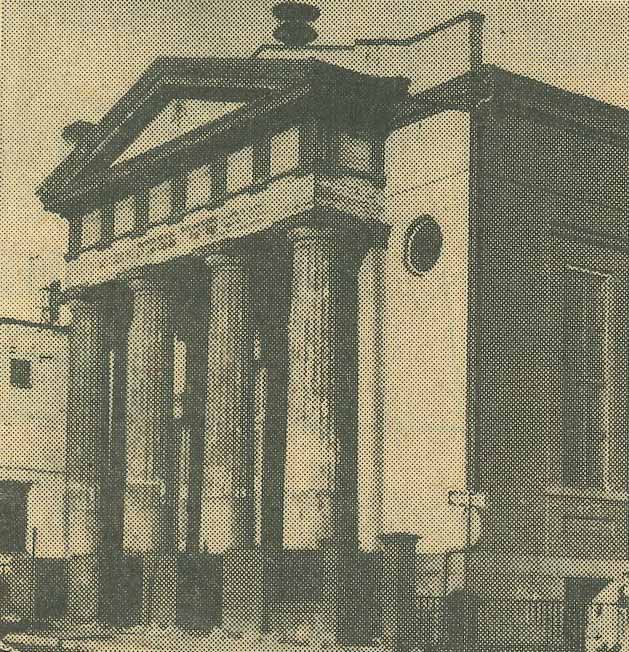

Despite the shabby condition of the leaking roof and dust-covered prayer benches, the interior still preserves the clean beauty of neo-classic style.

The nineteenth century architect of the recently discovered synagogue was also rediscovered. He was Robert Carey Long Jr., son of the designer of the Peale Museum.

According o Dr. Hunter, Long ligious edifices in the 1840’s: St. Alphonsus’ Catholic Church, St. Aphonsis Catholic Church, St. Peter’s Catholic Church, Mount Calvary Episcopal Church, and the Franklin Street Presbyterian Church.

From the outside of the neglected synagogue is still an impressive structure, set off from the street by a mixed wrought iron and cast iron fence.

Like most of Long’s other religious buildings the column-fronted synagogue looks down on the passerby from a raised pedestal.