Athenian Judaism…in Baltimore?

A blog post by Kierra Foley, LSS Archaeology Intern

A blog post by Kierra Foley, LSS Archaeology Intern

Hulking Doric columns and a stately pale façade cast shadows upon the sleepy downtown street, an imposing and authoritative presence in this otherwise aesthetically lackluster area. The building looks suited for housing a body of people pulsing with the commanding spirit of Athenian democracy, not necessarily the spirit of modern Western religious thought. Briefly, I scratch my head – if worship were to occur within this structure’s walls, it seems as though it would be of a pagan variety (specifically Greco-Roman!), but certainly not anything rooted in the Hebrew Bible, like the Jewish and Catholic congregations that have found homes here in years past. Even more likely, it looks to be an administrative or governmental building, a place that has little to do with worship altogether.

Over the past few weeks and for the coming weeks, this architecturally deceptive structure – the Lloyd Street Synagogue (or LSS) – has come to be my home. I’m both a Near Eastern Studies major at Johns Hopkins University and the JMM’s LSS Archaeology intern. For those of you who closely follow the oh-so-riveting lives of JMM interns, this is not your first time hearing from me, as I was the Collections intern this past winter. My task is to process everything within the synagogue, including objects recovered from recent archaeological excavations. Naturally, I spend a great deal of time within the synagogue, rifling through the endless of web of objects that call the synagogue home.

However, the outside of the structure has piqued my interest more than anything that lies within the building. Why would one make a synagogue so…stately? The physicality of Greco-Roman art has lost its spiritual integrity over the past few millennia, instead representing intellectual progress and highly structured administrative systems. This phenomenon occurs especially in American architecture, which from its outset aimed to embody the democratic ideals previously founded in Grecian antiquity. The Neoclassicism rampant in our nation’s capital is exemplary of this trend; this is simply an extension of the Revolutionary War era movement to borrow from Grecian antiquity in both scholasticism and politics – a movement pioneered in order to ensure a flourishing democratic state. Americans have adopted Classical architecture in order to establish visual harmony and organization, creating a statement of august power, a far cry from the spirituality Westerners so often achieve with the Gothic architectural principles of “height and light”. The B’nai Israel synagogue’s plan seems to full heartedly embrace the common modern practice of illustrating divine mystery via breathtaking architecture. Contrastingly, the Lloyd Street Synagogue makes no such effort.

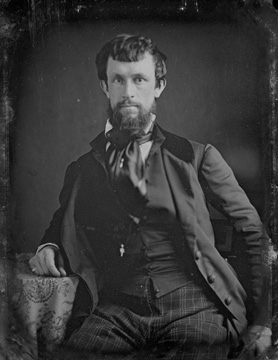

So, if not a communication of the sublime, what was the intended affect of the synagogue’s external aesthetic? It was constructed in 1845, the height of Neoclassicism, in the Greek Revival style. A clear disdain for Roman features can be observed in this building, rendering it Greek Revival in the purest form of the term. It was designed by Robert Cary Long Jr., Baltimore’s first native and trained architect. In many ways, Long was an architectural Renaissance man, wearing hats that ranged from the Greek Revival we examine here, to high Gothicism, to Egyptian Revival. A learned man, it’s more than likely that Long and the founders of the Baltimore Hebrew Congregation (the LSS’s first congregation who oversaw its construction) had a pointed intent.

Though far from an expert on such matters, from my time in the synagogue and my access to its inner workings and rich history, I have several theories developed as to why the synagogue was constructed in this way. The first reason being that the congregation wanted to remain inconspicuous, thus disguising themselves in a veil of Neoclassicism – an unlikely façade for worship. At this time, Jewish culture and religion was not met by gentiles with the utmost pleasure, and Anti-Semitism ran rampant through the streets of downtownBaltimore. With a wholly “American” covering for Jewish activity, the congregation could remain largely undetected by other intolerant Baltimoreans. In similar vein, the majority of the Baltimore Hebrew Congregation was comprised of German immigrants.

The attempt to “Americanize” the German mindset of the congregation was seen in its transition from strictly Orthodox to Reform in the early 1870s, as a campaign to modernize traditional behaviors was observable in new phenomena like the abolition of gender stratified seating in the April of 1973. The first step to modernization was taken in 1845 with the construction of the LSS, as it was a distant cry from all things German and a direct embrace of all things American. Still wholly Jewish, the building was also of the same nature as the American capital, beautifully merging both Judaism and the American spirit. Neoclassicism also may have been required to create an air of organization. The Baltimore Hebrew Congregation was one of the first established inAmerica, and a need to make the building an authoritative presence is valid, as this could potentially stimulate an air of reliability and productivity.

However, this is all postulation from the mind of an intern. Perhaps if we could go back in time and ask Long himself, he’d answer, “Oh, it just looked lovely!”