Bedlam with Corned Beef on the Side

The Jewish Delicatessen in Baltimore

Written by Barry Kessler. Originally published in Generations 1993, reprinted in Generations 2011 – 2012: Jewish Foodways.

Part I: Delicatessen Means Delicacies

The story of the American Jewish delicatessen cuts a revealing slice through the world of Jewish food and its regional and personal variations. The history of what Jews eat is a study of the many cultural forces in Jewish life: assimilation and tradition, secularization and religious observance, identity and commercialization.

In America, a unique form has emerged: the delicatessen, an ethnic grocery or restaurant – or a combination of both. In the atmosphere and foods of the delicatessen American Jews enjoy and present their culture as a flourishing folk life, transformed from traditional European roots into a richly textured secular ethnicity. The history of Baltimore’s delicatessens, the families and employees who made them, and the foods they served, trace a path through the Jewish presence in Baltimore from the turn of the century to the present.

“Delicatessen” means delicacies in German, and Webster’s defines the word as “prepared cooked meats, smoked fish, cheeses, salads, relishes, etc.,” or “a shop where such foods are sold.” Jewish delicatessens began as fancy grocery shops, specializing in importing and preparing foods familiar to recent immigrants, and slowly developed into the range of establishments we know today.

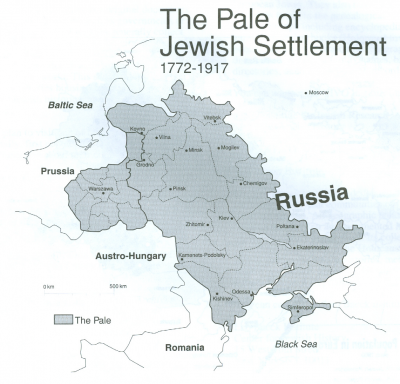

The varieties of food which today are considered to be Jewish delicatessen came to America with the Eastern European immigrants who flocked to America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From across the Pale of Settlement, ranging from the Baltic coast in the north to Odessa in the south, these immigrants mixed in the Jewish neighborhoods of American Cities, bringing their native foodstuffs.

Poor Europeans, both Jewish and Gentile, depended upon meat, fish, and vegetables preserved by smoking, pickling, or salting. To create kosher equivalents of some of the pork-based products eaten by their neighbors, Jews used cuts of beef, especially the easily koshered [made fit] brisket. Corned beef pickled in brine was favored in the northern and central regions, peppery pastrami in the south. Sausages ranged from hard and soft salamis and bolognas to the frankfurter, which originated in Germany. Smoked fish such as whitefish and lox (salmon) were specialties of the Baltic coastal regions and were exported all over Eastern Europe, but they were expensive delicacies eaten only by the wealthy or on infrequent special occasions. Poor Jews ate herring, a much more abundant fish: schmaltz herring, the cheapest and easiest to obtain, and matjes herring, from Holland.[1]

Many delicatessen foods, now eaten year-round, were originally associated with specific life-cycle events, holy days, or special occasions. For example, bagels, which appeared in Poland as early as the 1500s, were favored for bris [ceremonial circumcision] celebrations.

Traditional Jewish foods metamorphosed in America under the pressure of new social realities. New foodstuffs became available; most immigrants relaxed their observance of kosher laws and, as they prospered, could afford more frequent indulgence in luxury foods.[2] All of these forces were at work in the creation of the bagel spread with cream cheese and lox, a prototypical American Jewish edible which would have been unthinkable in Europe. Under the strict interpretation of some Eastern Eurpean rabbis, although fish was technically pareve [neither meat nor dairy], it was not to be eaten in combination with a dairy product such as cream cheese. Cream cheese itself was a new food immigrants encountered in America for the first time, and largely replaced the looser, saltier, farmer’s cheese they had eaten in Europe. Lox, while still expensive, was much cheaper in America with its greater supply of salmon, coming within reach of the average family.

Continue to Part II: The Old Neighborhood

Notes:

[1] Robert Sternberg, Yiddish Cuisine: A Gourmet’s Approach (Northvale, N.J: Jason Aaronson, October 1993].

[2] Andrew R. Heinze, Adapting to Abundance: Jewish Immigrants, Mass Consumption, and the Search for American Identity [New York: Columbia University Press, 1990].