Bernstein’s Style

Part 4 of “Saul Bernstein: Baltimore Artist,” written by Jobi Okin Zink, former JMM collections manager. Originally published in Generations – Winter 2001.

Part 4 of “Saul Bernstein: Baltimore Artist,” written by Jobi Okin Zink, former JMM collections manager. Originally published in Generations – Winter 2001.

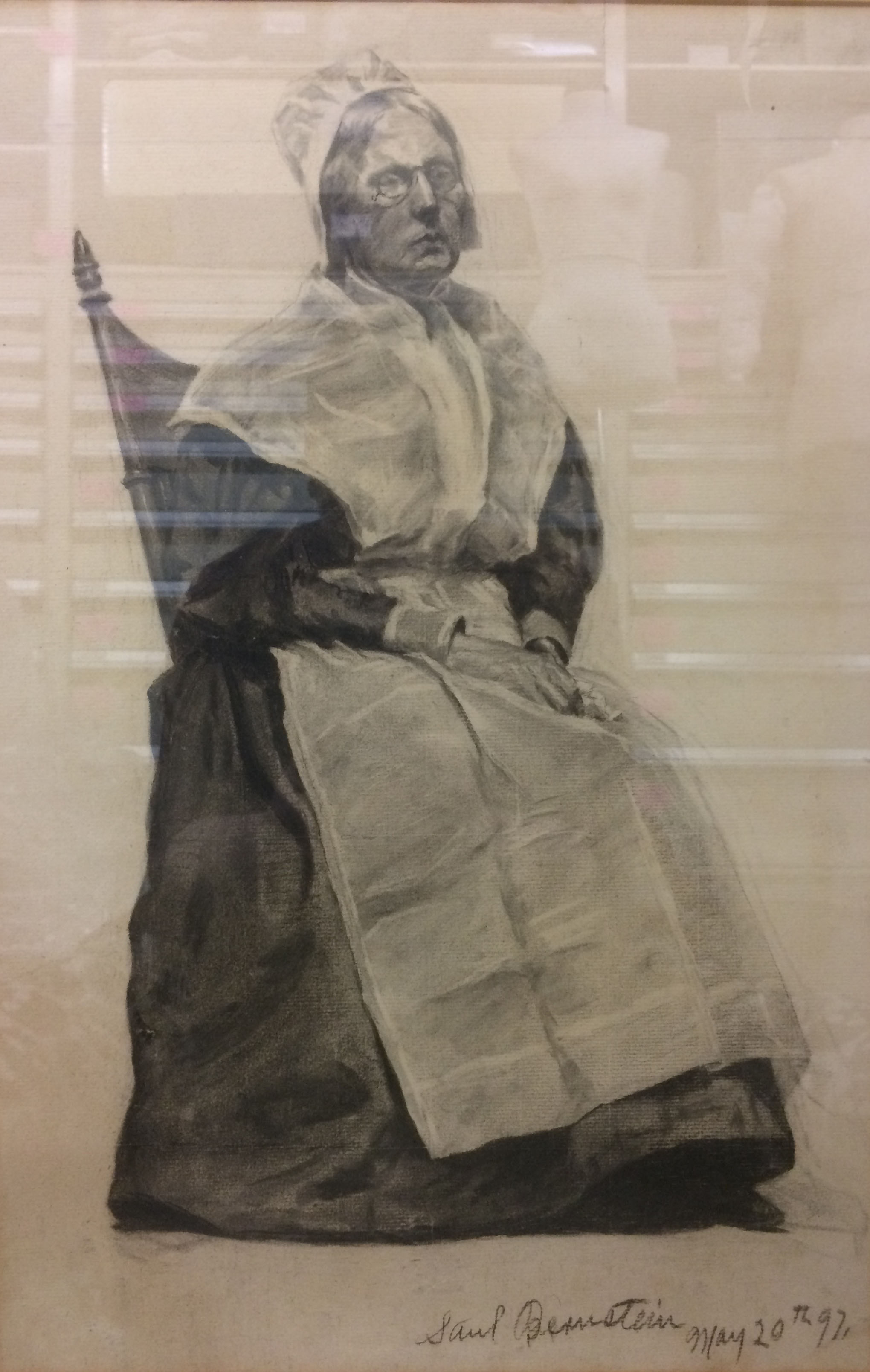

Several of Bernstein’s student works, including a charcoal drawing, “Woman Seated with Apron,” reside in the Museum’s collection and illustrate his mastery of the academic, traditional style. His ability to nuance shade and color convey the different weights and textures of his model’s lacy head covering, and heavy dress. It is easy to understand why Bernstein’s instructors offered favorable remarks about his works and recommended them for exhibition.

However, at the turn of the 20th century, Paris was the center for modern art and artistic innovation. Artists were no longer satisfied with painting the world literally as it appeared before their eyes. Impressionist techniques such as breaking up the surface of an artifact into bits and flecks of color, were spawning newer artistic methods. Although artists like Paul Cézanne and Henri Matisse were still a few years away from the breakthrough paintings that would inaugurate the Cubist and Fauvre are movements, they were already beginning to experiment with bright, vivid colors in unnatural combinations and to challenge the viewer by eliding the foreground and background in their paintings. In letters to Henrietta Szold and his brother Ben, Bernstein wrote that he was “uncomfortable” with the noise and heat in Paris, but one can also imagine that his discontent stemmed from a distaste for the new and unexpected approaches of modern art.

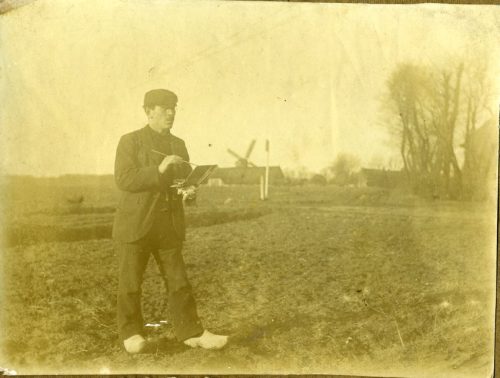

In the summer of 1900, after recovering from appendicitis, Bernstein moved to the small village of Laren, Holland. Here he continued to grind his own pigments and to paint in a traditional, academic style in which a painting of an apple looks like an apple and a representation of a chair reproduces the image of a chair. Bernstein used his landlord and local peasants as models and painted them as they were. The wrinkles on their faces and their gnarled fingers were neither imagined or exaggerated. Viewing Rembrandt’s paintings in Amsterdam enabled Bernstein to see how much variety he could achieve with a limited palette in his own works, particularly with the absence of blue in paintings like the Museum’s “Woman in A Chair.”

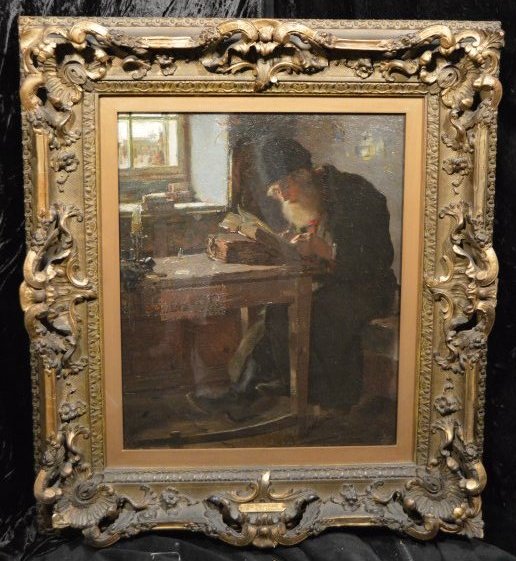

Not all of Bernstein’s paintings were of Dutch interiors or peasants. In 1900 he completed “The Talmudist,” which is also on display in Framing the Collections. Numerous Dutch influences are evident: a spare interior with a window; a dark shadowy palette like Rembrandt’s; a hint of the sitter’s inner psychology. Although “The Talmudist” is larger than Bernstein’s other Dutch interiors in the Museum collection, it too is not a formal portrait, but a painting that includes a three-quarter view of a male figure on the right side of the frame. The title indicates that the subject is not an individual, but rather a “Type.” The old man with a long flowing beard has his left hand cupped to follow a line of text in one of the volumes stacked on the table. The viewer senses the scholar’s dedication as he pores over his books. The text is not visible, but from Bernstein’s title one understands that he is studying a chapter of Talmud.

“The Talmudist” also differs from the majority of the works which hang salon-style along the Museum’s gallery walls in that the artist not only reveals character, but also evokes a setting and demonstrates his skill in rendering light and shadow. In the upper-left portion of the canvas Bernstein has painted a deep-set window with books arranged on its sill. The window-frame interior is a powder-blue that provides a strong contrast to the otherwise somber palette. The scene outside the window is blurred, preventing the viewer from recognizing the details of the setting; however, the viewer can follow the diagonal stream of light from the corner of the window, across the stack of books, and into the scholar’s face.

Another painting in the Museum collection, “Weaving Shop, Laren Holland,” also completed in 1900, demonstrates again how Bernstein can take a “type” and create a beautiful genre scene. The painting depicts a weaving shop with a large window across the back wall and a young man standing on the right. Again, the viewer cannot discern the setting beyond the glass panes. The blond-haired, blue-eyed man wearing a stereotypic Dutch cap with a small visor, a brown vest over a blue chambray shirt, brown pants, and oversized clogs, stares directly at the opposite wall, although there does not appear to be anything there to fix his gaze. A large wooden loom or weaving machine occupies the lower left half of the canvas.

Continue to Part 5: Bernstein and Szold, publishing on July 1, 2019.