Confronting “Difficult Knowledge”

with Eastern State Penitentiary

A blog post by Deputy Director Tracie Guy-Decker. Read more posts from Tracie by clicking HERE.

We spent time at the Eastern State Penitentiary, where I was surprised to find a restored synagogue. As interesting as that space was, it was not the most memorable I found at Eastern State Pen. For the most impact, I have to turn to what ESP staff calls “the big graph” and the small exhibit space they’ve carved out for Prisons Today.

Before I get to my experience of the graph and Prisons Today, let me back up to February of this year, when a number of the JMM managers attended the Council of American Jewish Museums conference in Washington, DC. (Read about our experiences here and here.) The conference theme was “Responsibility and Empowerment: A Civic Role for Jewish Museums,” and sessions explored the idea of museums as sites of conscience and as taking a stand. Rather than the “Dragnet” vision of museums of my youth (“just the facts, ma’am”), presenters at this CAJM conference invited Museums to take on the role of inspiring action—inspiring ‘upstanders’ to use the language of one of the featured institutions, the Take A Stand Center at the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center. Other featured sites included President Lincoln’s Cottage with their commitment to combatting contemporary slavery as a part of Lincoln’s legacy and…wait for it…Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP).

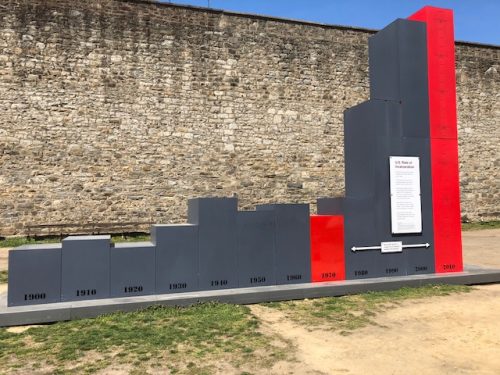

However, in recent years, staff and board have decided that they have a responsibility to use their platform to share a truth that is not always comfortable. They first developed the graph (see my picture below) a few years ago. It confronts the visitor with the reality of the current state of mass incarceration in America.

The graph is difficult to be with. The data was not surprising to me; I’ve read Michelle Alexander’s groundbreaking work The New Jim Crow, and I have spent a lot of time learning and thinking about the systemic nature of the racial disparities in our criminal justice system. The graph was still difficult for me to be with.

She said the staff talks regularly about helping people to work through the “learning crisis” that is triggered by confronting “difficult knowledge.” In fact, ESP provides continuing education sessions to the whole staff about the process.

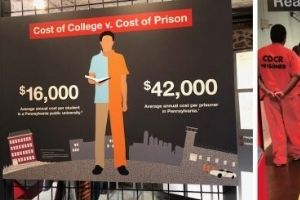

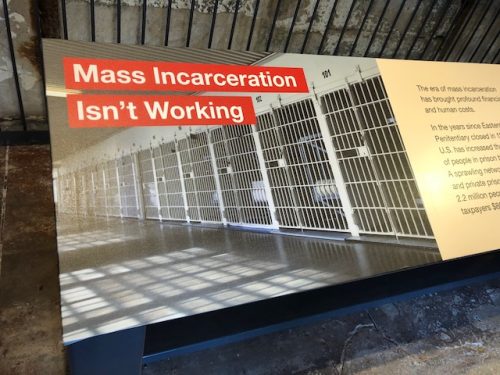

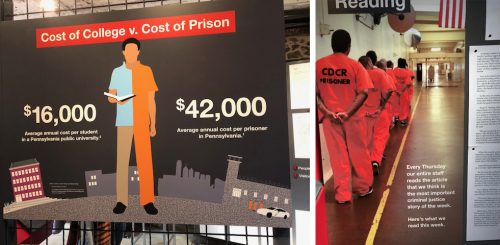

Our confrontation with “difficult knowledge” had only just started with the big graph. From the outdoor graph, we stepped into a well-appointed contemporary exhibition gallery for Prisons Today: Questions in the Age of Mass Incarceration, and were immediately met by this visually striking depiction of the reality of contemporary mass incarceration.

One interactive features hand-written statements of people confessing to criminal behavior. Visitors are asked to guess which ones were written by people in prison and which by other museum visitors. (The answers are surprising.)

I found myself both saddened and energized by the Prisons Today exhibit. Saddened because of the “difficult knowledge” that our justice system is decidedly unjust, and energized by the forthrightness and unblinking way in which the museum had engaged the question. I did not find the exhibit preachy or self-righteous, but informative and thoughtful. Best of all, it used the strengths of a museum-learning experience—the IRL-ness of it all—to make clear both the societal reality of mass incarceration and the personal realities of individuals who are affected by mass incarceration.

Their space is challenging—in the best possible way—without feeling judgmental. Even if a visit isn’t possible for you, you can take a virtual tour of the exhibit through the magic of the internet. This virtual tour is made available on the ESP website.