Dispossession and Adaptation Part II

Article written by Anita Kassof, former JMM associate director. Originally published in Generations – Winter 2002: Jewish Family History. Information on how to purchase your own copy here. Many thanks to JMM collections manager Joanna Church for re-typing this article.

Article written by Anita Kassof, former JMM associate director. Originally published in Generations – Winter 2002: Jewish Family History. Information on how to purchase your own copy here. Many thanks to JMM collections manager Joanna Church for re-typing this article.

Part II: An Odyssey Begins

Missed the beginning? Start here.

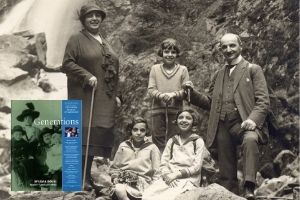

Before the Hitler period, the Weils were prominent, respected members of the community in Freiburg, a picturesque city in Germany’s Black Forest. Like most German Jews at the time, they were assimilated into mainstream German culture, but retained a sense of ethnic identity. Theo Weil was a successful businessman who had proudly served in the German army during the First World War. He and his wife, Hilda, had three daughters. Erna and Lisa, twins, were born in 1915. Toni followed three years later. The girls lived a life of privilege and security, although even as children they were aware that as Jews, they were different from their predominantly Catholic neighbors.

Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany in 1933. Immediately the Nazis began to institute anti-Jewish laws designed to stigmatize the Jews and cast them out from German society. Jewish professors lost their posts, civil servants were fired, and Jewish businesses were boycotted. In 1935, the Nuremberg laws defined Jews as anyone with at least one Jewish grandparent, stripping them of citizenship. The Laws circumscribed the Jews’ access to jobs and schools, and restricted their contact with non-Jews The Nazi legislation – and the concomitant rejection by former friends and neighbors – took the Jews of Germany, who were among the most cosmopolitan, highly educated, and assimilated Jewish populations in the world, utterly by surprise. As the Nazi party fomented anti-Jewish sentiment to strengthen its own platform, popular anti-Semitism bubbled to the surface.

The Weil sisters were just finishing their schooling when Hitler first assumed power. They experienced, first-hand, the pain of rejection that the new regime engendered. Former friends and classmates teased or excluded them. They had become outsiders, foreigners in their own land. Toni recalled wistfully that her girlfriends at school would not talk to her after Hitler came to power. When Nazi quotas on the number of Jewish students permitted at German universities threatened to dash Erna’s dreams of studying medicine, she arranged to attend medical school in nearby Lausanne, Switzerland. But before she finished her first semester, Nazi authorities discovered that Theo was sending Erna money for tuition and expenses. They accused him of smuggling currency from Germany and forced him to stop. Erna had to be content with studying to be a medical technician in Frankfurt.

Theo and Hilda did not feel the sting of rejection quite so acutely. The Weils had non-Jewish friends before the Nazi period, and some continued to socialize with them. Theo and Hilda still attended the theater and the opera. As a well-to-do woman, Hilda was able to maintain her comfortable household. Likely, she was able to insulate herself from potential hostility by sending her maid or her cook to do the marketing. Theo’s distribution business on the edge of Freiburg stayed afloat, although he did have to make some changes to comply with Nazi regulations governing both Jewish businesses and the distribution of raw materials. He continued to do business with non-Jewish colleagues and clients. However, because his business remained solvent, he was lured into a false sense of security in Germany.

“The trouble in Germany was things didn’t happen suddenly. It was a little and a little and a little, and you can always take a little more,” said Toni of the Nazis’ insidious anti-Jewish legislation. Like their parents, the Weil sisters proved remarkably adaptable in their constricting world. When the family was forced to dismiss their non-Jewish chauffeur in the wake of the Nuremberg laws, Erna and Toni applied for driving licenses so that they could drive their father – who had never learned to operate an automobile – to and from his office on the outskirts of Freiburg. Yet, as young women, they acknowledged that although they could adapt to a degree, they had no future in Germany. Their youth – and the fact that they were looking to the future rather than clinging to the past – explains why they, like so many others of their generation, emigrated more readily than their parents.

Continue to Part III: The Girls Get Out

All quotations and family history information are based on oral interviews with Toni Weil (JMM OH 0246, July 8, 1990), Julius Mandel (JMM OH 0268, June 23, 1991), Erna Weil, and Brenda Weil Mandel, and on materials in the Mandel collection (JMM L2002.102).