Dispossession and Adaptation Part IV

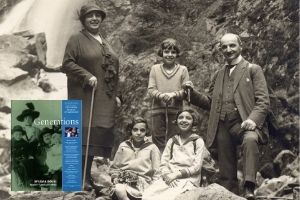

Article written by Anita Kassof, former JMM associate director. Originally published in Generations – Winter 2002: Jewish Family History. Information on how to purchase your own copy here. Many thanks to JMM collections manager Joanna Church for re-typing this article.

Article written by Anita Kassof, former JMM associate director. Originally published in Generations – Winter 2002: Jewish Family History. Information on how to purchase your own copy here. Many thanks to JMM collections manager Joanna Church for re-typing this article.

Part IV: Bringing Their Parents to Baltimore

Missed the beginning? Start here.

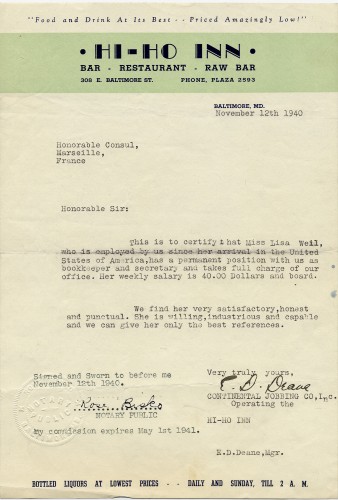

“There was nothing we would not do, and we enjoyed what we were doing,” recalled Toni of their first years in Baltimore. Still, their adjustment was far from easy. For starters, the only place they could afford to rent with the modest savings they had earned in England was a “fleabitten” room on North Avenue, near Fulton Street. Then they looked for jobs. In 1940 the United States was just beginning to emerge from the Depression, and the job market was still tight. Nonetheless, all three young women were working within days of their arrival. Erna became a practical nurse, boarding with her elderly charge on Homewood Avenue. Lisa got a job as an accountant for the Hi-Ho Inn, a Baltimore Street restaurant, and Toni found a position as a live-in governess for a family on Dolfield Boulevard.

As soon as they settled in, Erna, Lisa, and Toni turned to the task that weighted most heavily on all of them: helping their parents and their maternal grandmother, Lina Wachenheimer, come to the United States. In July 1940 the girls were relieved to learn that their relatives had been called to the U.S. Consulate in Stuttgart to undergo physical examinations and pick up their visas. They were free to leave! The girls quickly secured them passage via Lisbon, but by then Europe was engulfed in war. Although ships still sailed from Lisbon to the United States, land transportation between Germany and Portugal was almost impossible to come by. Tickets and visas in hand, the Weils were trapped in Germany.

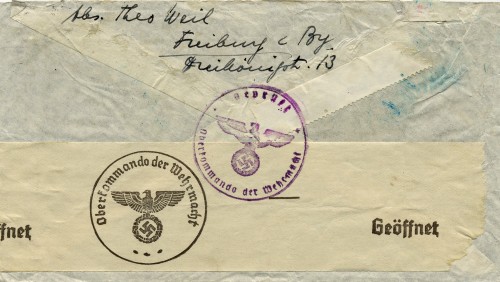

In September 1940, the girls sent their father a telegram on the occasion of his 60th birthday. It was one of the last communications they were able to send to him in Freiburg. In October, they received devastating news: the Jewish residents of Freiburg had been rounded up and ordered to report to a central collection point to be deported from Germany. The sisters learned of the deportations because Hilda had the foresight to grab writing paper and a pen as she was forced from her home. As the sealed train slowed down she thrust a letter through the cracks, hoping someone would mail it. She was fortunate; a passerby must have picked up a letter, because eventually it made its way to her daughters.

Hilda and Theo were among 6,500 Jews who were deported to Gurs from the Palatinate and Baden Würtenberg (where Freiburg was located) in October 1940. Nestled in the foothills of the Pyrenees mountains in France, Gurs had about 14,000 inmates. Inmates suffered from bronchitis, dehydration, heart disease, malnourishment, and dysentery. Rats spread communicable disease. The death rate was high, especially among older prisoners. Toilets were rudimentary, there were no disinfectants, and pools of stagnant water bred filth and pestilence. The wooden barracks lacked lights, stoves, firewood and flooring. Roofs leaked in the rain. Most prisoners, especially those who had arrived in the summer months, lacked adequate clothing and blankets. Official daily rations were barely enough to sustain them. Erna recalls that her parents later told her they had to eat and drink their watery soup out of rusty coffee cans.

The Weils have saved a black and white photograph of their extended family in Camp de Gurs in the winter of 1940. Theo and Hilda Weil, as well as Grandmother Wachenheimer and several aunts and uncles, are identified. A note in Toni’s writing reads, “others all related.” In all, 22 people sit looking at the camera in a weak winter sun. Were it not for the telltale rough wooden barracks in the background, and the looks of puzzlement on the subjects’ faces, it might have been a picture of a family reunion on a winter’s day, so many of them are gathered together. At that time, the subjects could not have known that the deportations of German Jews from France to the death camps in the east would begin in 1942.

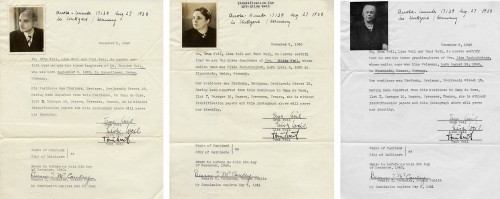

As soon as they learned of their parents’ incarceration, the girls marshaled their resources. Since Theo, Hilda, and Lina had already been approved to receive U.S. visas at Stuttgart, the first step was to have their paperwork transferred to a U.S. Consulate in France. Then the girls sought and gained permission from the State Department to send their relatives a stipend in the event they were not able to leave France as soon as they were released from Gurs. The $70 per month that they proposed forwarding represented nearly one-quarter of their combined salaries. They also secured affidavits from people in the United States and made preliminary arrangements for trans-Atlantic passage. Since their parents and their grandmother had been unable to take personal papers when they were deported, they had arrived in Gurs without identification. Erna, Lisa, and Toni took photographs of them to a notary public in Baltimore, and he created new identity papers, which they sent to France.

The Weil sisters repeatedly wrote the commandant at Gurs, pleading with him to look favorably on their request to free their parents and grandmother. One of the last letters they sent, dated January 11, 1941, reads, “We, the 3 daughters of Mr. and Mrs. Weil and the granddaughters of Mrs. Wachenheimer, beg you [Sir] to take pity and to permit them to leave for the United States, where they can live the rest of their lives along with their children.”

Their persistence paid off. Early in 1941, Theo, Hilda, and Lina were released, and the trio made their way from Gurs to Lisbon. From the vantage point of more than 60 years, we can only conjecture about how this elderly trio, weakened by months of inadequate rations and substandard shelter, made it over the Pyrenees, across Spain, and into Portugal. But they did, and in April, 1941, exactly a year after the girls came to America, their parents and grandmother arrived in New York. Lina stayed there with her daughter Sophie. Theo and Hilda continued on to Baltimore to live with their daughters.

Continue to Part V: Making a New Life

All quotations and family history information are based on oral interviews with Toni Weil (JMM OH 0246, July 8, 1990), Julius Mandel (JMM OH 0268, June 23, 1991), Erna Weil, and Brenda Weil Mandel, and on materials in the Mandel collection (JMM L2002.102).