Family Fare Part VI

Article by Jennifer Vess. Originally published in Generations 2011 – 2012: Jewish Foodways

Part VI: Marketing and Expansion: “We have to expand whether we want to or not.”[1]

In the time of the neighborhood deli and corner grocery store, proximity and word of mouth brought in business to the small shops. People walked to the closest bakery or learned from their friends if a better confectionary might be a few blocks further away. But by the early twentieth century, advertising and marketing became necessary for survival and particularly for growth. As more and more people owned cars and installed refrigerators, going long distances to stock up on food became more feasible. Sticking close to home wasn’t really necessary any more, opening up far more options for consumers. For owners who wanted to stay in business or for those who wanted to expand, advertising and marketing became crucial.

Advertising came in many forms. Large businesses with a big workforce and money to invest could buy ads of varying sizes in the local newspapers. The Jewish owned businesses in Baltimore reached out to the Jewish community through the Baltimore Jewish Times. Smaller businesses gave money in return for being featured in programs for local events, such as the Pioneer Club dance of 1937. Owners could show their support for the community as well as promote themselves. Businesses might also distribute fliers with their specials, or cover Baltimore with signs.

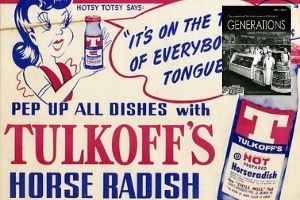

Name recognition has always been important to businesses. Turn of the century dairies used bottles imprinted with their names and logos. The small shops that became big businesses in Baltimore such as Hendlers Creamery, Silbers Bakery, and Tulkoff’s Horseradish Products Company, put their name and logo on product labels, signs, cake tins, and bags.

Aside from ads, packaging, and slogans, businesses big and small used promotional techniques to set themselves apart from their competitors and expand their customer base. Paul Wartzman, whose family owned Wartzman’s bakery once commented that, “Stone’s was the most successful bakery. They catered to a lot of non-Jews because they came out with a gimmick: hot rolls every half hour. I’ll never forget that. They killed all the other bakers. People would rush in for their hot rolls every half hour.”[2] Nates and Leon’s deli meanwhile drew in the crowds by offering something no one else did – round the clock service. Twenty-four hours a day customers could find a sandwich. This was particularly attractive to the people leaving nightclubs in the early hours of the morning.[3] Stones Bakery and Nates and Leon’s had more than just gimmicks in common – they both catered to the broader Baltimore community, expanding beyond the local Jewish residents. Expansion was a key step in the survival of Jewish food businesses.

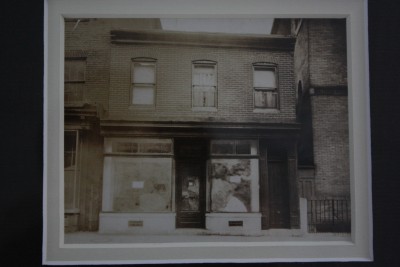

As marketing brought in new customers some small businesses outgrew their first floor shops. Wolf Salganik began as a butcher in a single building with his home on the second floor, but by the 1930s he and his sons had taken over multiple buildings where they carried out their wholesale meat processing on three floors.[4] Harry Tulkoff followed a similar pattern, starting out in a small grocery store in the 1920s then buying up several, connected buildings to convert into a single processing plant on Lombard Street before eventually moving out to their current larger location. Hendlers Creamery, Saval Foods Corporation, Silber’s bakery, Baltimore Spice, and others did likewise. Some of these businesses grew and sold out to other corporations, but others still exist today, still running and still growing and still in the family.

Expansion could mean creating an entirely new business. The corner grocery store was the forerunner of the modern supermarket, but supermarkets are more than just big grocery stores – they are a new entity that moved away from early twentieth century specialization to generalization. Baltimore saw its first supermarkets before World War II. Businesses like Food Fair (a national supermarket chain that started in the late 1920s) and the local, Jewish-owned Food-O-Rama and Shreiber’s supermarket changed how families shopped. “The Shreiber Brothers did the impossible. They made a store where you had not just meats, but you had groceries. Then they brought in their own baker. By adding on they had the supermarket. It [may have been] the first supermarket in the entire country.”[5] Today, in addition to regional and nationwide chains Baltimore has local supermarkets such as Eddies, and Seven Mile Market, the latter not just Jewish owned but also aimed at the Jewish community.

Impact and Legacy

The stories of family-owned Jewish food businesses have not stopped being created. Many small shops closed, leaving behind only the fond memories of scents and tastes that can never be duplicated. Other businesses that began long ago still exist today run by third or fourth generation owners providing the old standards while staying close to their historical roots. And new businesses continued to open.

Restaurants, bakeries, and delis continue to open, owned and operated by Jewish men and women – often to serve the Jewish community. Local entrepreneurs (or transplants from elsewhere in the US) establish new businesses, and so do recent immigrants. Families from places like Israel, Iran and Russia arrive in Baltimore and start their own restaurants or bakeries or delis, using their knowledge and skills of food from their former homes to support their families. Jewish family food businesses have long been a part of the local economy, and though the world is very different today than it was a hundred years ago, the stories of living and eating and family fare remain constant.

Continue to Sidebar One: The Bluefeld Catering Story: “People came from all around”

Notes:

[1] Howard Saval, 1982 Baltimore Sun

[2] Paul Wartzman interview, June 5, 2006, OH 686, JMM.

[3] Mina Shavitz interview, March 33, 3002, OH 648, JMM.

[4] Gordon Salganik interview, n.d., OH 318, JMM.

[5] Louis and Philip Bluefeld interview, August 6, 1979, OH 75, JMM.