Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving

A blog post by Deputy Director Tracie Guy-Decker. Read more posts from Tracie by clicking HERE.

Several weeks ago, Joanna Church and I were in Brooklyn for a meeting, and Joanna suggested we check out the Frida Kahlo exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum. She said there were more Kahlo canvases in one room here than there had been since her death. When Joanna’s text first came across my phone I immediately thought of some of Kahlo’s iconic self portraits (and then of her skeletal appearance in Disney’s Coco. What can I say, I am the parent of a first-grader), and I tried to remember the last time I’d seen a Kahlo canvas up close. As I wracked my memory, I realized I had never seen a Kahlo painting in person.

On entering the first room, the exhibit was not what I expected. There were very few examples of Kahlo’s work, but a great deal of artifacts and photos from her life. From the very beginning, this exhibit helped me to deepen my understanding of Frida Kahlo, a figure who had become somewhat two-dimensional in my imagination.

My first surprise was realizing that Frida Kahlo was born Magdalena Frida Carmen Kahlo. In my two-dimensional caricature of her, Frida is unequivocally Mexican. That is undoubtedly true of the three-dimensional woman who lived and loved and painted, but IRL, Frida Kahlo was so much more complicated than I had given her credit for. One of her complexities was that even with her decidedly Mexican identity, she chose to go by the German “Frida.”

Just as they deepened my sense of the complexities of her identity, the curators of this exhibit provided me with context for Kahlo’s paintings—both personal, political, and cultural. Among the cultural context was a great deal of information about the history and usage of some of the costumes featured in Kahlo’s portraits. The most notable may be the Huipil Grande she wears in Diego on my mind. I was entranced by the illustrations of the article of clothing—totally unknown in my life experience—and appreciated the vintage film of young women wearing them.

(As an aside, it is really interesting to peruse museum exhibits with other, trained museum professionals. At one moment, early in the exhibit, I approached Joanna who was examining one of Kahlo’s scarves under a vitrine. She frowned and said, “I wouldn’t have displayed this that way.” Before I worked at JMM, I can tell you I never once heard or said that to a fellow museum-goer!)

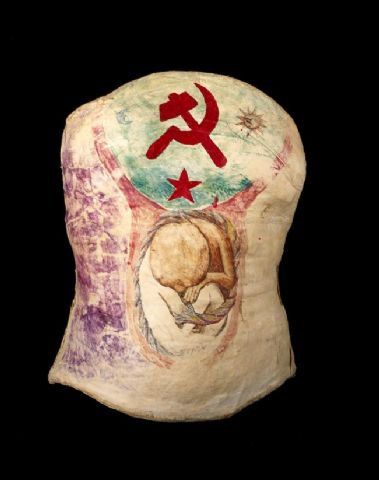

Despite the reason I decided to come see the exhibit, the real heart of the Brooklyn Museum’s display is not Kahlo’s paintings. It is a trove of her clothing. According to the handout from the museum, “In 2004 a remarkable trove of personal items belonging to Frida Kahlo was brought to light at her lifelong home, the Blue House (La Casa Azul), in Mexico City. Locked away at the instruction of her husband, Diego Rivera, following her death in 1954, these materials—including exceptional examples of her vibrant wardrobe—are here displayed in the United States for the first time.”

A deeper insight than the realization of the role of Kahlo’s disabilities in her clothing choices, was my new-found sense of just how deliberate all of Kahlo’s clothing choices were. The garments on view in Brooklyn suggest that she was regularly altering, modifying and pairing garments in unusual ways. Kahlo was highly aware of the connections she made (or rejected) for herself by what she wore and how she presented herself. She used her clothing to assert her affiliations and her heritage. She used her clothing to fashion her private and public identity.