Hiking through History

A blog post by JMM Executive Director Marvin Pinkert. You can read more posts by Marvin here.

It’s that time of year. Our wanderlust leads us to unexplored spaces. A straight line may be the shortest distance between two points – but then you’ll miss all the scenery. Some like to wander through mountains, some like to meander down a beach, but my favorite place to go hiking is through the pages of history. If you let yourself stray off the main path, there’s no telling what surprises you might find. I thought I would share some of the twists and turns I’ve recently experienced.

Three weeks ago, I was preparing to speak at the Museum of Howard County History (MHCH) in Ellicott City. My topic was the history of the Jews of Howard County and the MHCH had actually prepared a small exhibit on this topic in 2016. The exhibit included the agricultural colony of Yaazor. Zig. Technically speaking Yaazor was located in the Woodlawn community of Baltimore County but it was pretty close to the Howard County line. I asked Lorie if we had anything in the archives on Yaazor. She presented me with a paper on the colony written by BHU student Deborah Silberman in 1983. Zag.

The paper contained an amazing story from the son of the community’s shochet who said that during Prohibition his father slaughtered chickens by day and (to make a living) brewed bootlegged whiskey at night. The son goes on to report that when “I was thirteen years old in 1928 when the Catonsville Police came to my home and pointed their guns at my father… the police allowed him to write a note asking a neighbor to care for our farm, but the message, written in Russian, actually asked the colonist to destroy the still.

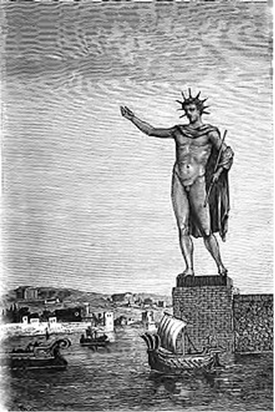

Some hikes actually take me across a bridge from one topic to another. Two weeks ago, I was getting ready for an interactive discussion of American immigration laws and the Jewish experience at B’nai Israel (as part of their annual Shavuot Limmud program). My plan was to use primary sources to tell the story. I thought, what better place to begin than Emma Lazarus’ poem The New Colossus, contrasting its call to send us “wretched refuse” with recent proposals from WhiteHouse.gov for “merit-based” immigration. Then it hit me – what if some in the audience don’t understand the reference to “Colossus.” Zig. With the reduction in history education in elementary school, it seemed that it was no longer a safe bet that everyone knew the Seven Wonders of the World. For a quick refresher, I looked up the “old Colossus” (i.e. the Colossus of Rhodes) in Wikipedia. Zag.

The same story is recorded by Bar Hebraeus, … “And a great number of men hauled on strong ropes which were tied round the brass Colossus which was in the city and pulled it down. And they weighed from it three thousand loads of Corinthian brass, and they sold it to a certain Jew from Emesa” (the Syrian city of Homs). Theophanes is the sole source of this account and all other sources can be traced to him.

It appears that, according to Theophanes, a 7th century Jewish scrap dealer used 900 camels to cart away the statues remains and recycle them. I didn’t end up using this anecdote at Limmud but it may make a feature appearance at the opening of the Scrap Yard exhibit in October.

Finally, there are times when you feel truly lost in the woods but being lost is not necessarily a bad thing. I was helping prepare the script for our upcoming showcase exhibit, Redeemable: Baltimore’s $2 Bill and the Making of American Currency. The featured artifact in the exhibit is a $2 bill signed by revolutionary patriot, Benjamin Levy. I thought that the easiest panel to write would be the biography of Mr. Levy. After all, nearly every website (including JMM’s) credits him with being the first permanent Jewish settler in Baltimore (1773) Zig. But the question I found debated on the web was whether Benjamin Levy was truly Jewish?

The question is not as absurd as it sounds. A genealogy search revealed that both Benjamin and his wife Rachel had been born into a prominent New York Jewish family (and it appears that they were cousins). While in one sense this settled the matter, it still left open the question of whether they were practicing Jews. One site that questioned their affiliation mentioned that they were buried in an Episcopal cemetery. However, further research revealed that when Rachel died in 1794 there wasn’t a Jewish cemetery in Baltimore – the first wasn’t created until 1797. And though Benjamin dies in 1802, perhaps he had expressed a strong preference to be buried beside his wife. Zag. Further exploration in Jacob Rader Marcus’ expansive history, United States Jewry 1776 -1985, led to a realization that of the Levy’s five children, two married outside the faith and the other three remained unmarried. By the fourth generation in America, there were no Jewish descendants of Benjamin and Rachel Levy.

The trails of history are endless. I encourage you to explore them this summer. I can’t think of a better trailhead than the Jewish Museum of Maryland.