Jews Migrate to Small Towns

Part 2 of “Strangers No More: Jewish Life in Maryland’s Small Towns. Missed the beginning? Head there now! Written by Karen Falk, former JMM curator. Originally published in Generations – Winter 2001. If you would like to purchase a hard copy of this issue, please contact our shop, Esther’s Place, at 443-873-5179 or email info@jewishmuseummd.org.

Part 2 of “Strangers No More: Jewish Life in Maryland’s Small Towns. Missed the beginning? Head there now! Written by Karen Falk, former JMM curator. Originally published in Generations – Winter 2001. If you would like to purchase a hard copy of this issue, please contact our shop, Esther’s Place, at 443-873-5179 or email info@jewishmuseummd.org.

Jewish settlement in small towns most often followed a pattern of deliberate emigration form the city, employing a process historians call “chain migration.” People who had tired of the dirt and poverty of the cities, who hoped to build a better future in a less crowded place, were often following the counsel of relatives, landsleit (fellow countrymen), neighbors, and even strangers who had preceded them to the small towns. Hannah Hirsch Cohen tells a typical story:

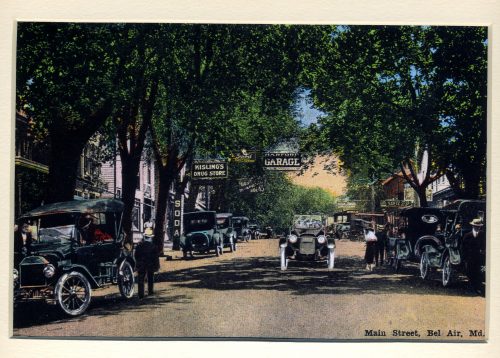

My father’s brother told him, ‘Ben, there a little town near where I work. It’s called Bel Air. It’s a nice little town and they could use another good tailor there.’ So Mother and Dad came here (from Philadelphia) and they looked the town over and they decided to stay here. That was in 1923.

Benjamin Hirsch brought his wife to Bel Air and established a men’s clothing store where he showcased his talents as a tailor. The store Hirsch opening is still operated by his daughter and son-in-law, in only its second location.

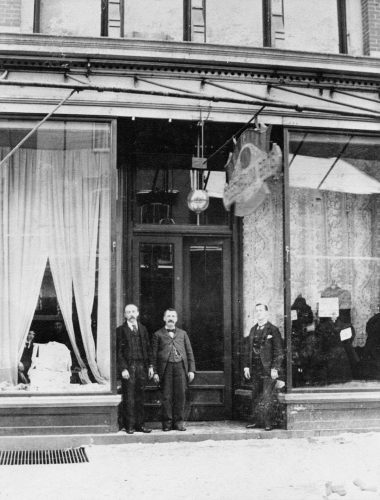

A mid-19th century example of chain migration from the growing railroad town of Cumberland, in western Maryland had notable consequences for the town. Brothers Henry and Selig Adler were among the Jews who had established mercantile businesses there in the 1840s. They sent to Germany for their nephew Simon Rosenbaum, to assist them in the store in 1865; his younger brother Susman joined him in 1869. A decade later, the Rosenbaum, brothers bought out their uncles’ business and established the largest department store in Western Maryland.

Jews also discovered the opportunities offered in small towns while working as peddlers. The memoirs of Samuel Weinberg, a native of Hanover, Germany, provide a colorful description of his arrival in Frederick after a series of difficulties in making his way from Virginia to Maryland during he Civil War. After peddling from 1852 to 1860 in Frederick, Washington, Carroll, and Montgomery Counties in Maryland, Weinberg had moved to Winchester, Virginia less than a year before the outbreak of the war. A man with Northern sympathies, Weinberg was treated unfairly by his Confederate employer, a local merchant, and felt himself in physical danger. He was forced to take his wages in merchandise rather than money, and then was prevented by the authorities from taking the stock across the border to Maryland, from South to North. He sold at a loss in Winchester and gladly took the train to Frederick, Maryland, where he determined to settle.

Happily, Weinberg’s flight to Frederick landed him in friendly territory. There he joined several other Jews who had come to the United States from Central Europe. Weinberg wrote in his memoirs:

My intention was to open business for myself, but Mr. James Landauer persuaded me to clerk for him until the spring if 1862. This I did with the understanding that when I wanted to go into business for myself, Landauer would recommend me for credit, but when the time came for me to leave, Landauer refused to help me, as he wanted to retain me as a clerk. However, my mind was fully made up, and with $300 at my command, I embarked in the confectionery business.[1]

In addition to offering employment, the Jewish men of Frederick witnessed for one another at citizenship hearings, celebrated together when a bris (circumcision) occurred, and insured a Torah in 1864, indicating that regular worship services were being held.

The earlier experiences of the Adlers, Rosenbaums, and Weinberg, and the later experiences of Hannah Cohen’s family should be understood in the context of 19th and 20th century Jewish demographic patterns. In 1830, the Jewish population of the United States was only about 4,000, concentrated mostly in the large Eastern Seaboard cities. By the late 1870s that population had increased to about 250,000, due largely to the immigration of Jews from such Central European areas as Bavaria, Prussia, Alsace, and Posen. These “German” Jews settled in cities, such as Baltimore, as well as in smaller, regional urban centers such as Cumberland and Frederick. Maryland’s oldest congregations – Baltimore Hebrew Congregation (organized 1830), Har Zion (organized 1842), and Oheb Shalom (organized in 1853) in Baltimore, B’er Chayim Congregation in Cumberland (organized 1853) and Frederick Hebrew Congregation (not officially chartered by certainly meeting as early as 1856) – are products of this wave of immigration.[2] There were also several Jewish families and a nascent Jewish community in the Hagerstown area, as indicated by records of several weddings at which a Rabbi Levi officiated between 1851 and 1856.[3]

The German Jews had backgrounds similar enough to other Americans of the time that it was not difficult for them to blend in. They became merchants and industrialists, and often took leadership positions in their adopted communities. Their success and acceptance by the wider American community also led to assimilation and, particularly in smaller communities, to a reduction in the number of people identifying as Jews. One consequence of this pattern was that Frederick Hebrew Congregation had ceased its regular meetings by 1890.

The years from 1880 to 1924 are known as an era of mass immigration, when the population of the United States grew by 56 million people, and Jews from Eastern Europe swelled in numbers to almost four million.[4] The vast majority of these newcomers went to cities. The number of Jews in Baltimore, for example, grew from 10,000 to 65,000 during these years.[5]

The experience of these “Russian” Jews was quite different from that of the earlier Germans. The East European newcomers often arrived in America with few funds, little secular education, and limited skills. They stood apart from American society – and from established American Jews – in language, dress, and manners, as well as in their approach to Judaism. In addition, the sheer magnitude of their numbers made it even more difficult for them to assimilate.

Jews of this new wave of immigration also found their way to Maryland’s small towns. The process of chain migration continued to operate. Friends and family encourage newcomers to join them in small towns such as when Hannah Cohen’s father, a tailor in Philadelphia, was tipped off by his brother to an opportunity in Bel Air. Immigrant Jews also answered ads for employment and businesses for sale in small towns. Yet another vehicle for Jewish settlement in small towns was the Industrial Removal Office which operated from 1900 to 1917, promoting Jewish settlement in smaller cities around the country including Maryland. In some towns these Eastern European immigrants added new strength to languishing older communities, while in others they broke completely new ground.

Continue to Part 3: Putting Down Roots (publishing February 4, 2019)

[1] From the “Autobiography of Samuel Weinberg,” unpublished typescript, n.d., Jewish Museum of Maryland vertical files.

[2] The Occident and American Jewish Advocate, Vol. 14, No. 9, December 1856 mentions “many Israelites in Frederick and Hagerstown.” Further description of this period in Frederick’s Jewish history may be found in Paul and Rita Gordon’s The Jews Beneath the Clustered Spires, 1971, pp. 34-49.

[3] Anniversary booklet, 80 Years of Congregation B’nai Abraham, Hagerstown, Maryland, 1892-1972.

[4] Jacob Rader Marcus, comp., To Count a People: American Jewish Population Data, 1585 – 1984 (Lanham, MD, 1990).

[5] Baltimore’s population statistics may be found in Earl Pruce’s Synagogues, Temples and Congregations of Maryland, 1830 – 1990, Jewish Historical Society of Maryland, 1993.