JMM Insights: Jewish Ireland?

This month’s JMM Insights comes from shop manager Chris Sniezek, who volunteered to do some history research in honor of St. Patrick’s Day!

According to Maria Goody ( NPR), “the Irish didn’t learn to love corned beef until coming to America, where they picked up the taste from their Jewish neighbors in the urban melting pot of New York City.” I love eating corned beef and cabbage on St. Patrick’s Day and it was not until I began working for the museum that I realized corned beef was a Jewish-Irish influenced food.

Right: “St. Patrick Eats Bagels” pin collected by the Zulver brothers. JMM 2008.43.2.

Before, it was just the food I always consumed on St. Patrick’s Day. Now, I am unable to walk through the “Voices of Lombard Street” exhibit without recognizing the significance of the Attman’s and the “Corned Beef Row” street signs.

With this culturally significant and a more subdued St. Patrick’s Day finished, I wanted to know what, or if, there was a strong Jewish presence in Ireland. To start, I first checked out past JMM blog posts, searching for any blog, which discussed Irish Jews.

I found former Collections Manager, Jobi Zink’s post “Everybody is Irish on St. Patrick’s Day”; a fun blog recounting growing up with Irish festivals and a trip to Ireland, but nothing much on the Jews living in Ireland. So I dove into some more materials at my disposal and here is what I learned!

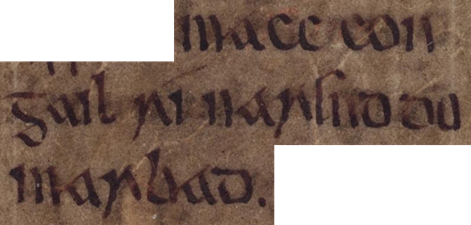

The first permanent Jewish community to settle Ireland cropped up near Dublin. Even though this community was established quite early on (late 13th century), the permanent Jewish population on Ireland remained very low; demonstrated by the construction of the first synagogue in 1660 and the first Jewish cemetery in 1718.

The establishment of a synagogue and cemetery was one of the most important events in the establishment of an early Jewish community since it demonstrated to English parliament a persistent and growing subsection of potential citizens. The growth of a Jewish presence in Ireland and the establishment of a house of worship lead to the inclusion of Irish-Jews in a 1746 naturalization bill (also labeled “The Jew Bill”).

However, this did not mean widespread acceptance because Irish-Jews were expressly left out of the Irish Naturalization Act of 1783, which provided legislative independence to the country. The 1746 bill originally meant to increase the “productivity of the Jews and their potential contribution to English commerce.” This meant Jewish individuals living in Ireland were Irish citizens and subject to Ireland’s rule on top of British rule, an important recognition for such a small population even if there were ulterior motives.

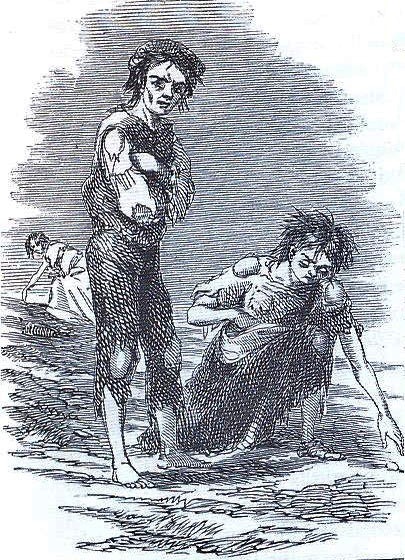

In the mid-1840s, the Irish Potato Famine decimated Ireland’s population, both through starvation and emigration. The Jewish population, the majority of whom were merchants near Dublin instead of farmers, became an exception to this rule because their professions enabled them to purchase food rather than growing their own.

While such instances of national turmoil usually spike instances of antisemitism, the Irish Potato Famine appears to lack this spike (from the records I have found). In an act of compassion for the Irish people, Jewish synagogues in America and Britain collected over $1,500 and £600,000 in aid compared to the US and foreign governments which pledged $50 and £3,000 respectively. The influx of aid from Jewish organizations appears to help mitigate some anti-Semitic behavior and rhetoric in Ireland.

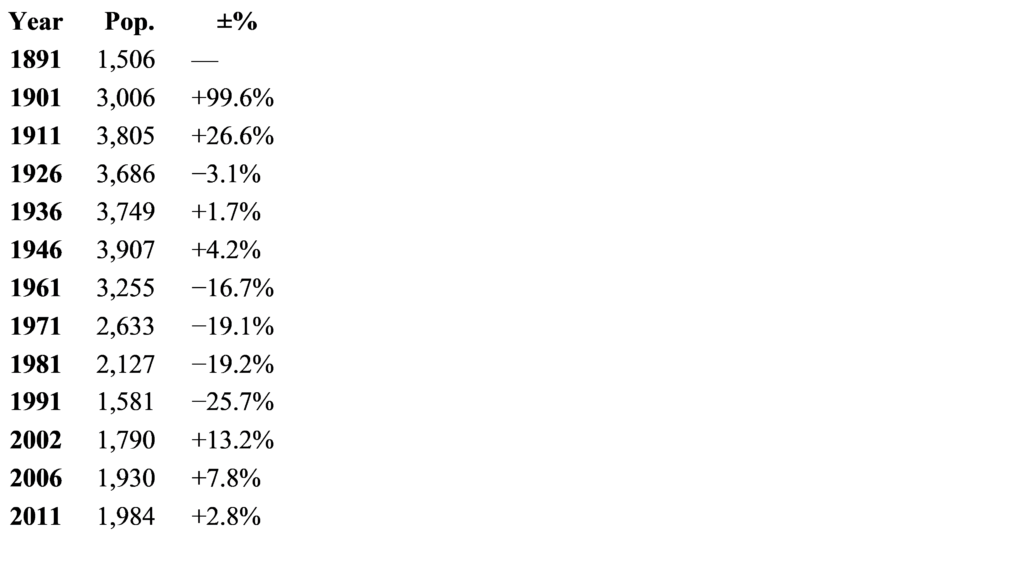

By the late 19th century, the Jewish-Irish population had doubled in size (to 453 individuals) becoming a theme for the next half century. Immigration (both voluntary and forced) from Central and Eastern Europe bumped the Jewish-Irish population to almost 4000 individuals by 1940 (.13% of the total Irish population).

This growth led to the establishment of several more synagogues within Jewish communities, reaching half a dozen synagogues across the country by the end of World War Two. The 1940s onward witnessed a decline in the overall Jewish-Irish population as immigration slowed and emigration rose as fast as assimilation. As a result, by the early 2000s the Jewish-Irish population is a fraction of the previous size.

While the Jewish-Irish population appears to have stabilized over the past decade, hovering around 2000 individuals, many congregation leaders worry about the decline and eventual eradication of Jewish-Irish culture.

As Belfast native Nora Simon perturbs, “Children go away for university now, and they don’t come back” which further exasperates the strain on the community. This decline in the Irish-Jewish population has led to the closure of multiple synagogues across the country, but that does not mean Jewish-Irish culture is any less vibrant. The remaining congregations have increased their community outreach as a way to carry on and foster positive relationships with their neighbors and other religious communities.

For those looking to explore the history of Ireland’s Jewish population first-hand once international travel resumes, the Jewish Community Office in Dublin wrote up a historical route tour here: https://www.jewisheritage.org/web/routes/pdfs/Irish_Jewish_Route.pdf. This interesting tour guides visitors through some if Ireland’s historic districts and the current communities to create a robust understanding of Jewish-Irish culture.

Overall, this has been a very fun and interesting research topic and I encourage anyone who is interested to check out some of these links below!

~Chris Sniezek, Shop Manager – Esther’s Place (and History Enthusiast!)

Further reading sources:

- https://irishhistoryfiles.wordpress.com/2015/01/05/history-of-the-jews-in-ireland/

- https://www.jewishgen.org/jcr-uk/ireland.htm

- https://jguideeurope.org/en/region/ireland/

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43058619.pdf

- Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the Immigrant Menace by Alan Kraut

In Case You Missed It:

The live recording of “In Conversation with Joy Ladin” is now available:

Watch Here.

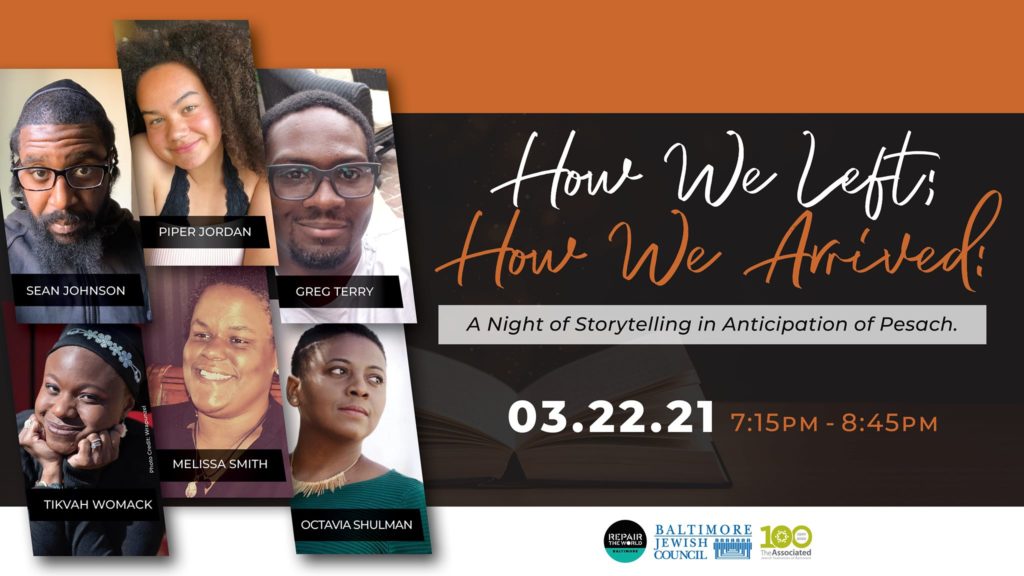

What if I don’t connect to the term Jew of Color (JOC)? Can’t I just be a black person who makes Shabbat? What is being chosen and what is tokenizing? Why these questions and why now?

Pesach is the season of asking important questions and telling stories about the circuitous journey from oppression to liberation, both as history and as a continuous process that each of us must see ourselves part of, in every generation.

Join Repair the World, Baltimore Jewish Council, and Rabbi Jessy Dressin for a night of storytelling, reflection, and identity as we prepare for Pesach in community.

Esther’s Place: Online

Passover is just around the corner – so don’t delay. Check out our newest Passover-themed bundles now – plus our selection of Seder plates, Elijah’s cups, and more.

Did you know: Skip the shipping charges and choose “Curbside Pick Up” at check out!

Reminder: Executive Director Sol Davis is holding weekly office hours to meet you! Make an appointment for a virtual visit and share your thoughts, ideas, and aspirations for JMM.