Match Point Part III

Article by Barry Kessler with Anita Kassof. Originally published in Generations – 2004: Recreation, Sports & Leisure. This particular issue of Generations proved wildly popular and is no longer available for purchase.

Article by Barry Kessler with Anita Kassof. Originally published in Generations – 2004: Recreation, Sports & Leisure. This particular issue of Generations proved wildly popular and is no longer available for purchase.

Part III: An Interview with Mitzi Freishtat Swan Continued

BK: Tell us about the follow-up, after the event. What was the trial like?

MFS: The trial took place in October 1948 in Baltimore City Criminal Court. The judge was Herman Moser. The prosecutor was Alan H. Murell. And the defense attorneys were I. Duke Avnet, Harold Buchman, William Murphy, and Edgar Boyko. The charges against us were conspiracy to create an unlawful assembly in a public park, and violating park rules by refusing to obey orders of Park police. We were also charged with entering into a conspiracy for the express purpose of disturbing the peace. Those were the charges.

And the Park police were called to testify then and they said the same thing they said in Magistrate’s Court, where they mentioned the singing of songs, that and they didn’t like being called names like Gestapo or something like that. And Alan Murrell, in arguing the case, said, “Are we going to substitute in this city, this state, and this land, under our form of government, revolution for evolution?” And Avnet’s defense was, “No matter how much the state tries to hide it, the real issue is what are the rights of our people, and whether discrimination such as this is legal under the constitution of the Federal government and the State of Maryland. What is on trial here is persecution. What is involved are the rights of colored people.” He pointed to the history of persecution along the lines of religion and labor, and declared that in each instance, when these matters came before the courts, the real issues were camouflaged. Judge Moser said at one point, “Assuming this rule is so, I don’t see much sense in a rule banning interracial sports in one section of the park and then selling tickets in another section interracial games such as baseball and the like.” Which is really a very good statement.

So the charges were dropped against 17 defendants for violating park rules. Seven were convicted of conspiring to unlawfully assemble and disturbing the peace. The sentence was withheld pending new trials. They appealed it and they were found guilty of conspiracy. And they had a suspended jail term. The seven charges that were sustained were the people charged with disturbing the peace. They had to drop charges against the players. There was a lot of pressure going on, because there was no law against what they were doing.

AK: Did any of the protesters lose jobs or suffer other serious consequences as a result of their activities?

MFS: I know that most of the black men who worked at the post office were fired. Some of the white protesters suffered some consequences but they didn’t actually lose their jobs. See, a lot of us were students. Some of them went to Maryland, some of them went to Morgan. Some people were postal workers, we had some who had been seamen, and we had some who worked in steel mills. We were a whole big conglomeration of different kinds of people who, in ordinary life, you wouldn’t have met them.

AK: That fall, you started college. Tell us about that.

MFS: I went away to college, to the University of Maryland, and my life got involved in all that. I have to tell you, there were repercussions in college from people who met me, because the press was very negative. The press red-baited us like crazy. Every time the articles came out, everybody’s name was listed. And I would think, oh no, here we’re going to go again with another whole big bunch of stuff in school. It was not welcomed, it was not welcomed.

In my own family, my mother’s sister was appalled, saying, “How could you let your daughter do something like this?” You know, horrible. And, in turn, her son, who was my cousin, had some friends who went to Maryland. And they used to come back with stories that people weren’t talking to me, really digging it in. Actually, some people supported you, but most people didn’t. They did not want to see integration take place. They wanted the status quo. But most people just ignored it.

AK: Were you involved in politics at all at Maryland? Were you still a member of the Young Progressives?

MFS: Yes, we tried to keep a group going but the school made it very difficult to reserve a room. They really didn’t want us to be there. As to the group that had organized the protest, I was away at school, people had different jobs, and then the elections ended and it just fell apart. You’d see some of the people sometimes but it wasn’t a cohesive group.

BK: I wonder if you could go back and tell us a little bit about growing up near Druid Hill Park in terms of the sports and the recreation activities that you and your friends were doing in the park. What role did the park play in your life?

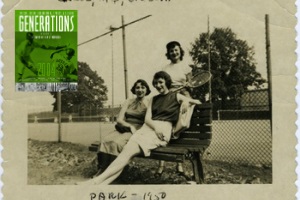

MSF: The park was a big thing. We used to play tennis there. We also used some of the pavilions for picnics. We used to go out there with a group. Not as the Young Progressives, but just in general to take picnics. They also had baseball games there. I was already too old to go on the playground but I used to pass the playground (I moved near the park when I was about thirteen years old). Where I was living tennis was a big thing. There were a lot of players who were very good. Tennis was a big thing in the neighborhood because the courts were there. These were clay courts but we were also close to the other courts, the concrete courts. I don’t think they use them anymore. I used to walk it all the time because also right where those courts were there was the swimming pool, which was a white swimming pool. So we used to go over there all the time because we used the pool all the time.

Pictured includes Hy Zlotowitz (Hy Zolet) on left, back center is Royal Pollokoff.

BK: What about the larger, say, Jewish community around the park? Was there a sense that the protest was the right thing to do or did they respond negatively?

MFS: Let me give you an interesting story. My grandfather was a cantor in the synagogue. He was very Orthodox and he lived in the neighborhood. And he never, ever said a word against it. Ever. He, I mean he loved me just as much as before.

BK: Did you get the sense that because many people in the Jewish community were progressive that they supported what you were doing”

MFS: I wouldn’t say that. Most of the people were apolitical. They were not the least bit concerned because they were conscerned with their own families and things like that. They were not interested in African Americans in particular. Even people who were liberal didn’t do anything to show their support, in particular. People are afraid to do that.

AK: Did being Jewish have anything to do with your motivations for joining the protest?

MFS: Oh, absolutely. My mother and father were immigrants to this country and my mother as a child lived in Russia. She came from one of these small towns. And being Jewish there, you were victims of the pogroms, as she was. But she was also a very smart kid, and she could pass the test that allowed her to go into the Russian schools. So she went to the Russian school, but she got hit with stones every day when she walked to school, and taunted. And this was when she was very young, six, seven years old, because she came over to this country when she was 13 or 14. And so my mother always told me those stories about what prejudice does, and I grew up with those stories. So it was just a step forward, that if the Jews are persecuted like that, you know black people were being persecuted the way we were. And so that just fell into my way of thinking.

BK: In your neighborhood and in your daily life did you have any interaction with black people? You were obviously someone who believed strongly in civil rights, but did you actually interact with black people on a day-to-day basis?

MFS: There wasn’t much interaction. You have to understand, the neighborhood was all white, and the only interaction I would have would be at Young Progressive meetings. Other than that, there was no interaction. The schools were segregated, everything was segregated, so there was just no way that there would be any interaction at all. There was no real avenue for meeting African Americans. The movies were segregated, everything was segregated. I mean, there was no crossing anything. So there was no way that you would even know anyone that was African American in your regular life because your regular life just didn’t cross with theirs.

BK: What effect did the protest and the court case have on policies? Did it suddenly become possible for black and white people to play on the courts together?

MFS: It did, but not suddenly. Segregation gradually stopped, because I know that my brother played in the first interracial tennis match in that park, on the same courts, with the Baltimore Tennis Club.

BK: After the protest, did the Young Progressives feel as if they had won a battle against segregation?

MFS: It’s an interesting question. You know, in hindsight, I didn’t realize at the time what we were doing, that is was really such a historical event. We just did it because we thought it was the right thing to do. We hoped that that would be the beginning of a change, but we didn’t know at the time.

AK: Now it’s a badge of honor, what you did during the Civil Rights era. When do you think the attitudes began to shift, from your being ostracized or criticized for what you did, to being honored for what you did?

MFS: The biggest honor was in 1989, when Barry did the exhibition about Baltimore’s parks and the Baltimore City Life Museums organized a reunion. But earlier, in 1982 or 1983, the Baltimore Tennis Club invited us to come out to their games and we were introduced to their players and the other people that were there. It was the last day of their match. And the young people there had never known that the tennis courts were ever segregated! They had no idea. And that surprised me. I would have thought that parents would have told them.

I tell you, the only thing I really regret is that my husband didn’t live to see when we were heroes instead of people calling us name and everything. We were vilified, and then all of a sudden we were heroes. My grandson thinks what I did was the coolest thing! The youth of today is much different than when I was young. They are more activists, they’re more aware of what’s going on. When I was growing up, most of them couldn’t care less what was happening, so it’s heartening to me – even though some of them I don’t agree with – but that they’re doing something, standing up for what they believe in. I find that very heartening.