Museum Insights, July 19, 2013

Those of you who follow our blog posts may have noticed the accent this summer on Civil War stories (June 28, July 2, July 3). This reflects not only the 150th anniversary commemorations but our own work in preparing for next fall’s exhibit. I have asked curator, Karen Falk, to tell you a bit about her take on what makes this exhibit important.

Insights from the Civil War

It may come as a surprise to some, but all American Jews can find a connection to the Civil War, whether or not they have ancestors then in the country and in the conflict.

At least, that’s our observation, based on our work with the upcoming exhibition, Passages Through the Fire: Jews and the Civil War, which will open at the JMM on October 13. (Thank you to the organizers of the exhibition, the American Jewish Historical Society and Yeshiva University Museum.) Here are some ways that I’ve connected with the story.

The Jewish debate over slavery. Daughter of the sixties that I am, I was brought up to believe that social justice was a central tenet of Judaism. I’ve learned, however, that such thinking was not as common among the Jewish immigrants of the mid-19th century as it became for later generations. Jews were divided on the question of slavery: they tended to gravitate towards the opinions of their neighbors, North and South. As new immigrants (of 150,000 Jews in America on the eve of the Civil War, 100,000 had been in this country for a decade or less) struggling to make a living and unsure of their place in American society, most Jews preferred neutrality.

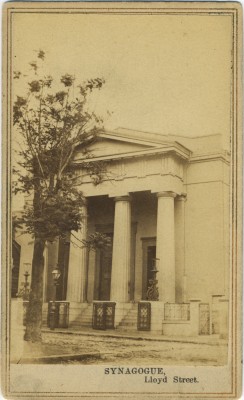

There were those, however, who expressed strong opinions, among them, the rabbis of Baltimore. Rabbi Bernard Illoway, who served Baltimore Hebrew Congregation from 1859 to 1861, defended slavery from the pulpit saying, “Why did [Moses] not, when he made a law that no Israelite can become a slave, also prohibit the buying and selling of slaves from and to other nations? Was there ever a greater philanthropist than Abraham, and why did he not set free the slaves which the king of Egypt made him a present of?”

Rabbi David Einhorn of Har Sinai Congregation (1855-1861) was incensed by this biblical justification of slavery by Rabbi Illoway and other rabbis. A staunch defender of human rights, he also used the Torah to support his position: “The ten commandments, the first of which is: “I am the Lord, thy God, who brought thee out of the land of Egypt,—out of the house of bondage” can by no means want to place slavery of any human-being under divine sanction….”

Rabbi Einhorn’s views enraged the secessionist-leaning population of Baltimore and he fled the city, taking a pulpit in Philadelphia. Rabbi Illoway also left Baltimore soon after his speech, for a pulpit in New Orleans.

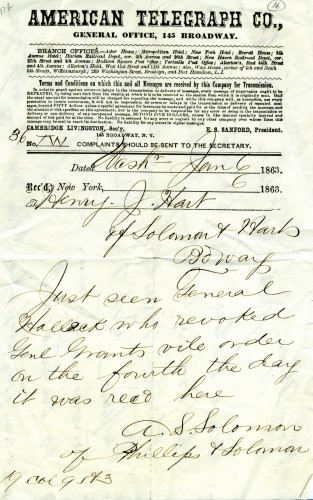

The attempt to expel the Jews. The Civil War era was not without anti-Semitism. There were commonly-repeated canards about the Jews: they didn’t fight in the military; they were profiteers; they were cunning cheats. At its worst during the war years, these doubts about the Jews translated into General Ulysses S. Grant’s infamous Orders No. 11, whereby “The Jews, as a class violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department and also department orders, are hereby expelled from the Department [including Kentucky and parts of Tennessee and Mississippi] within twenty-four hours from the receipt of this order.”

Grant issued his order on December 17, 1862. Fighting in his area delayed dissemination of the order throughout the whole of the territory he governed, but enforcement began immediately in Paducah, Kentucky. (Kentucky was a border state: slave-holding but part of the Union.) Jews throughout the country raised an outcry. One man ousted from his home, Cesar Kaskel, immediately traveled to Washington, DC, seeking an audience with President Lincoln. He was seen and supported by the president, who directed Grant to revoke his order.

All of this happened quickly; the order was officially rescinded by Grant on January 17, 1863. American Jews had learned something very important about their home. As historian Eli Evans observes, “the Northern Jewish community had stood beside the Jews in the South, demonstrating a sense of community that transcended sectional bitterness. Jews [in the Union] had publicly petitioned their government to revoke an order by its most popular general in the midst of a war, and the head of the nation had agreed.” Jews had come together to protest an injustice, had been heard, and been protected.

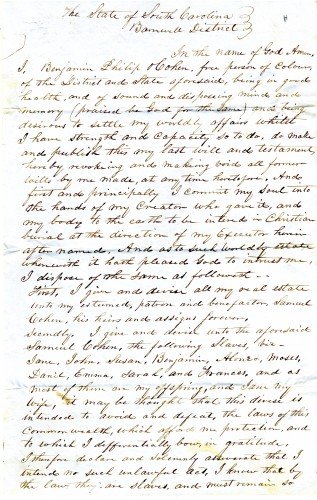

It’s personal. Civil War stories often illuminate difficult personal decisions. One such story is told by one of the most remarkable documents in the exhibition, a draft of a will for Benjamin Owens Cohen. Cohen, his Jewish father, Barnet Cohen, and non-Jewish mother Catharine Owens, a “free woman of color,” lived in South Carolina. As a free person of mixed race, Benjamin Cohen would have had limited potential marriage partners, so he purchased his wife and owned their children. By 1841, when he was thinking about a pathway to freedom for his family, South Carolina was passing laws that made it nearly impossible to simply emancipate one’s slaves. His will thus bequeaths his wife and children to his white half-brother. On advice from his lawyer, Cohen stated in his will that while “it may be thought that this devise is intended to avoid and defeat the laws of this commonwealth, which affords me protection….I therefore declare…that I intend no such unlawful act. I know that by the law, [my family] are slaves and must remain so….”

This draft of Cohen’s will is part of an AJHS collection documenting Cohen’s situation. Scholars have been unable to find a legally-filed will for Benjamin O. Cohen, and we do not know how the family resolved the problem. Historian Bertram Korn suggests that “perhaps Benjamin Owens Cohen outlived the institution of slavery and was able to spend his last days with a family freed from involuntary servitude.” I hope so, too.