Of Mah Jongg, Passover and Cultural Adaptation

A blog post by Executive Director Marvin Pinkert. To read more posts from Marvin, click here.

We are just a few days away from the opening of Project Mah Jongg. Throughout the last month the team has busily been preparing. Ilene has been developing activities for kids, Trillion has been working on program concepts and Rachel has been applying her creativity to ways to let people know the exhibit is here.

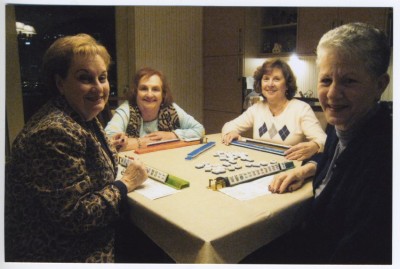

As for me, I’ve been using my weekends to research a little bit about the history of Jews and board games. This is a convenient convergence of the needs of the project and my personal interests. I have been in the museum business 25 years, but I’ve been playing board games – nearly continuously – for at least 55 years; moving from the childhood classics (Candyland, Monopoly, Risk, Stratego) to the 3M games of the 1960s to Baltimore’s own Avalon Hill war games of the 1970s to the rail games of the 1980s and the Eurogames of the 1990s. I have somewhere around 150 board games in the basement, not enough to make me a collector, but more than enough to have my wife wince every time she sees a new box come through the door. To prepare for the exhibit I have also learned Mah Jongg (it’s tough work, but someone has to do it).

Since we signed up for the exhibit, I have been intriguing audiences with the question “how did a game for Chinese menbecome a pastime for Jewish women?” The empirical answer to this question involves Jewish flappers of the 1920s and Jewish charitable fundraising in the 1930s. But this statement of facts sidesteps a more interesting question about Mah Jongg as an example of cultural adaptation. Mah Jongg is just one example of many things that both Jews and non-Jews would point to as culturally Jewish that have no theological basis, no connection to Torah or Talmud – e.g. bagels on Sunday morning, Borscht Belt shtick, discount camera supplies.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the Abba Eban-narrated PBS series, Heritage: Civilization and the Jews. The point of the series was that Judaism had not merely survived 4,000 years of contact with other cultural communities, it had actually helped shape (and in turn was shaped by) those contacts. With the passage of enough time we often loose our awareness of cultural adaptations and assume that our customs are native to our history. In researching games, I found a fascinating example: dreidel. Like many of you, I grew up thinking that the game of dreidel was contemporary with the Maccabees. But with a little on-line searching I learned that the game probably becomes a part of Hanukah in the 17th century. The dreidel is based on a top called a teetotum and a game known as “put and take” that originated in England in the 1400s. In the following century, the top moves to Germany where it gains some familiar letters – G for “ganze”, H for “halb”, N for “nicht” and S for “stell ein” meaning “put in”. It became a popular Christmas game in Germany. Like “potato latkes” (19th century) and “gift giving” (20th century), dreidel is a piece of the Hanukah celebration borrowed from our neighbors and given new meaning in a Jewish context.

Of course at this time of year my senses are more likely to be excited by the anticipation of matzah kugel than the memory of latkes. However, Passover too is a great example of the history of cultural adaptation – running the gamut from ancient rites of spring to the Roman custom of free men reclining to the contemporary examples of suffering and depredation often invoked during the recounting of our bondage in Egypt. I have often looked at the seder as an archeological dig, not only through Jewish history, but through all the cultures we have touched.

So perhaps it is not as unusual as it seems to include Mah Jongg among our adapted treasures. We have made the meld and now it’s a part of us.

4 replies on “Of Mah Jongg, Passover and Cultural Adaptation”

Hi….I don’t know who to contact so I’m hoping you can steer me in the right direction. We are watching the movie Avalon. The movie takes place mainly between Thanksgiving Day 1948 to Thanksgiving Day 1950. Can you tell me what the Jewish population of Baltimore would have been back then? If you don’t know maybe you could pass my email onto someone you think might know.

I haven’t been to Baltimore in over 35 years, I used to work for the Canadian Division of Life-Like Products, and came to meetings in Baltimore and I also use to come to the Preakness Stakes many times. with friends. I like Baltimore…..but since I’ve retired, I go to Florida a few times every winter, I hate the cold weather here in Toronto.

Thank you

Jeffrey Siegel

Hi Jeffrey,

That’s a pretty big question! I would recommend you contact our research@jewishmuseummd.org email address for some suggestions on where to start reading up!

Best,

Rachel

Jewish Museum of Maryland Web Maven

Please email the city schedule for the traveling mah jonng exhibit. Thank you

Hi Candis – not sure what you are asking for here? Project Mah Jongg will be on display here at the Jewish Museum of Maryland through June 29, 2014.