Operation Finale and the role of art in teaching history

A blog post by Deputy Director Tracie Guy-Decker. Read more posts from Tracie by clicking HERE.

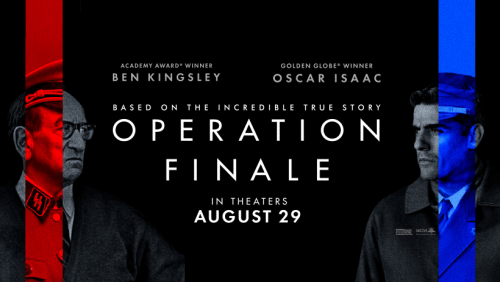

Back in July of this year, Trillion Attwood, the JMM Program Manager, was approached by a promotional company arranging for pre-release screenings of the new movie Operation Finale. Their goal was to create buzz around the Ben Kingsley–Oscar Isaac film that dramatizes the Israelis’ 1961 capture of the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann. The promotional company wanted to know if we would be willing to host a screening if they would pay to rent the theater space at a cinema near our location.

We knew we wanted to do more than just a film screening, so we immediately got in touch with our colleagues at the United States Holocaust Memorial and Museum (USHMM) in Washington. They were planning their own DC-area screening with this same promotional company, but they were still excited to partner with us on our Baltimore screening. We also reached out to our colleagues and partners at Baltimore Jewish Council for their partnership. Together, the partners decided to do a talk-back after the film, with a facilitated conversation between an historian from USHMM and our audience. We decided I would be the facilitator.

In the days and weeks after the decision to proceed, it became clear that Marvin and I were not the only people figuratively jumping at the chance to see this film. We did very little promotion for the event (we didn’t have much time), and still saw tickets sell out in about 48 hours. Our staff fielded phone calls and emails of folks desperately hoping to score a seat. (Luckily for them, the movie is being released in theaters this Wednesday, August 29.)

I admit that I knew very little of the details of the capture of Eichmann in Argentina before watching the film. The filmmakers do an admirable job of building and holding suspense for the viewer. I felt my heart race several times as I watched. I was also struck by the nuance with which the movie depicted not only the Israeli operatives who carried out the mission in Argentina, but Eichmann himself. In the conversations after the film, some of my fellow audience-goers worried that the film made Eichmann too sympathetic. I did not find him particularly sympathetic—the film does not shy away from his monstrosities—in fact, in one memory, we see over and over, Eichmann oversees the field execution of thousands. His lack of compassion and disregard for what he oversees is depicted through the banality of his concern over the cleanliness of his jacket. I was, however, impressed with the three dimensions that the filmmakers and Ben Kingsley lent to the character. As one of our audience members put it in their survey response, “Ben Kingsley’s performance as Eichmann” showed “how someone so boring and ordinary can become so evil.”

My big question to the audience that night was “what role does art like this have in the teaching of history?” There was some disagreement. One gentleman lamented that movies like this disseminate misinformation. He suggested that most of us in the audience already knew the story, and perhaps the filmmakers should have left well enough alone. I countered with a question. What about for my daughter, who is six years old? She is unlikely to know any survivors into her adulthood. Does art have a role in keeping the story alive for future generations like her? If the answer is yes, do the art-makers have license to make the audience heart race even if the adrenalin-filled chase to the airport is a little less-than accurate?