Oral History: Connecting through time

Blog post by Public History Intern Rebecca Miller. To read more posts by and about interns click HERE.

Through recorded oral histories, we preserve information that is not found in data tables, census records, or even preserved media. During the Great Depression, my great-grandfather actually attended and graduated high school twice, but this is not recorded by the government. His younger brother had found a job to help support the family, but was still required by law to finish his schooling. Jobs were hard to find and important to keep so for the sake of his family, my great-grandfather went back to finish high school for his brother. This story is an oral history passed down through my family. It is a story that would be lost without word of mouth and is not in any official record. If you were to look for a graduation record for Raymond Haber, you would only find one.

Familial oral history has preserved Ray Haber and his brother to my family, but if this story is not recorded it can be lost to humanity. This little anecdote is potentially a handy tool to understanding the dynamic that held families together during the Great Depression, but if I do not tell the story it will fall to the wind and be lost to future generations. Oral histories once recorded and transcribed take on solid form and are better preserved for the future. Recording these histories through an organization like the museum gives more people access to the stories that have shaped generations.

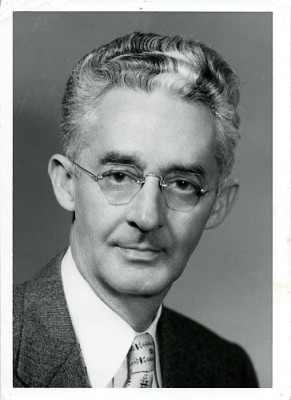

The Jewish Museum of Maryland, its employees, and volunteers have compiled around 800 oral histories since they started in 1963. The first oral history in our archives is an interview with Jacob Edelman. Edelman and his interviewer, Dr. Isaac Fein, met on 6 February 1963 to talk about the garment industry in Baltimore.

These days we use equipment that creates immediate digital copies that can be accessed easily on a computer. While the recording technology has changed significantly since 1963, the basic idea of collecting oral histories remains the same. Our purpose is to preserve not only the voices of our interviewees, but more importantly their stories, insights, and overall humanity.

He was a boy of 15½ with no marketable skills, whose Russian and German were better than his Yiddish and had no English fluency whatsoever. The Hebrew Immigrant Agency & Sheltering Society helped him when he arrived and told him that the garment industry was the best place for him to find work, so that’s where he went. From this position, Edelman was privy to the strikes and unionization of the industry. He himself was a striker. He claimed that the strikebreakers were Europeans and that they were “broken by importations of scared, strikebreakers and many innocent, well-intentioned people that just got off the boat because boats were coming in every day… they didn’t know any better” (Jacob Edelman, OH0001: Jewish Museum of Maryland, 1963). His sympathy and explanation for the strikebreakers is a humanity best seen through oral history.

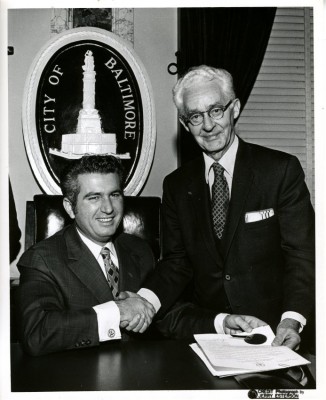

Edelman’s oral history is but a snapshot of his life and his involvement in the Baltimore area. From 1939 to 1971, he sat on the Baltimore City Council, first for district four and then for district five. He came from humble beginnings as an immigrant with no family or connections. He lived through the unionization of the garment industry and increased his personal status from an immigrant with nothing to a politician with family.

Even though it is a brief recording, Edelman’s oral history keeps his memories alive. He is here at the museum, preserved in the words he spoke on 6 February 1963, explaining the Baltimore garment industry of the 1910s.