Teach, and be taught.

A blog post by intern Erika Rief.

As an Education and Programming Intern at the Jewish Museum of Maryland, I initially assumed that I would impart on others my knowledge about Baltimore Jewish history either on tours, group visits, or through the children’s activity packs I am creating. Especially with my background in genealogy, I hoped to use my experience to inform others about their past. Now, reflecting on the past six weeks, I realize how much I’ve learned by teaching others.

Every week Ilene Dackman-Alon, the museum’s director of education, visits Tudor Heights, an assisted living on Park Heights Avenue. There, she tells a personal story to elicit stories of the past from the residents. Through storytelling, Ilene is able to gather information about Jewish Baltimore from the best sources while giving the elderly people a chance to express themselves by recalling the past.

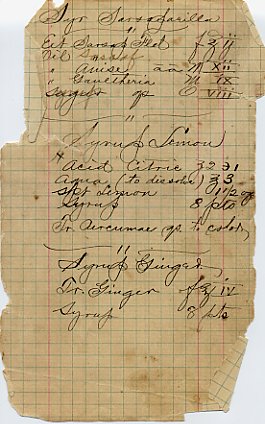

One day, Ilene asked me to look up whatever I could find about Joseph Goldsmith. Joseph’s daughter, Zelda, lives at Tudor Heights. She unfortunately never knew her father because he died shortly after she was born. All I knew about Joseph before starting my search was that he had a pharmacy on the corner of Lloyd and Lombard Street, which is on the block next to the museum. Zelda had given the museum a photograph of him and a receipt from the pharmacy. Ilene gave me the name of Zelda’s mother, Bessie (nee Mallow) Goldsmith and Zelda’s parents, Louis and Fannie Mallow. Skeptical of what I could find without birth dates, I got to work.

Two hours later, I had uncovered the 1910 Federal Census of Louis and Fannie Mallow along with the 1910 Federal Census of Joseph’s parents and siblings. Therefore, I now had birth years for all of Zelda’s grandparents and the years of immigration for her parents and grandparents. In the 1920 Federal Census, I found Joseph and Bessie’s entry which was recorded around the same time that Joseph passed away. By 1930, Bessie had remarried and bore one child with her second husband. The three of them plus Zelda and Joyce, the two daughters from Joseph, were now living with her parents, the Mallows.

Federal censuses provide interesting tidbits of information, like addresses, occupations, how many children a women had given birth to compared with how many were living, place of birth, and place of parents’ birth. However, my luck in finding Joseph’s naturalization papers was what enabled me to really get to know him. In 1917, at 51 years old, Joseph’s statue reached a towering 4 feet 10 inches. He had black hair, brown eyes, weighed 143 pounds, and under distinctive marks ‘hunch back’ is noted. He was born in Warden Russia on January 17, 1886. On February 21, 1905, he arrived at the port of Philadelphia from Liverpool, England. In addition to the naturalization papers, I found Joseph and Louis’s World War I draft cards which further confirms Joseph’s hunch back condition and the details I had found in the censuses about Louis.

When Ilene first asked me to look up information about the pharmacist on corner of Lloyd and Lombard, I don’t think she expected the abundance of information I ended up revealing. After spending hours acquainting myself with Zelda’s family, I was anxious to meet this 92-year-old woman with such a fascinating family history. Yesterday, Ilene accompanied me to Tutor Heights. However, due to Zelda’s health, we were not sure if she would be there. Sure enough, as soon as we walked in, there was Zelda, sitting in a circle with the other residents learning about Tu B’shevat.

We wheeled her into the dining room. After Ilene explained to her why I was there, I began taking her through each document I had found. With the details from Joseph’s naturalization papers, I was able to paint a visual of the father Zelda never knew. However, she remembered a lot more than I had expected and was able to confirm some questionable details. For instance, the 1910 Census said that her grandfather, Louis Mallow, was from Scotland and that his second child was born in Scotland but the first child was born in Maryland. I assumed that all mentions of Scotland were incorrect. Zelda confirmed Scotland as her grandfather’s birthplace and explained that the family had returned to Scotland because of a dying relative. While visiting, Louis’s wife gave birth to their second child. Zelda explained that Louis went back and forth to Scotland often. This explained a ship manifest I had found with Louis Mallow’s name from 1913 with a home address listed on Lombard Street.

Besides the information I provided to her, there were many details that no matter how hard or long I had searched, I would never have discovered. Zelda’s anecdotes added a whole other dimension to my work. While researching, I found it interesting that Joseph was 14 years older than Bessie and only 10 years younger than her father. What I didn’t know was that Zelda’s grandparents disapproved of the age difference but thought the world of Joseph. Also, every time Bessie prepared food for Joseph, he would tell her how wonderful she was. Zelda talked and talked and I inhaled every word. As I sat there, I understood what an incredible opportunity this exchange had been. A precious piece of Baltimore Jewish history that would otherwise have been forgotten will now live on. Thrilled to pieces about all that I had given her, Zelda doesn’t realize all that she has taught me.