The Other Side of the Photograph

One of the many charms of working with vernacular photograph collections—that is, photos that were not intended as fine art—is that they come with their own special kind of provenance. I do not refer to any folder full of certificates indicating dates of purchase and previous owners, but to the history that is conveyed physically on the surfaces of a photograph whose owners never expected it might hang in a museum someday. The result of this sort of treatment, if occasionally a little cringe-worthy from a conservator’s perspective, is a rich source of narrative and culture from a historian’s. Most of these photographs have been handled, scrapbooked, lost, found, framed, passed around at parties, and generally enjoyed before they join the JMM’s collection—and they show it. While scanning sometimes hundreds of photographs a day, I end up examining a lot of photograph backs, and sometimes I wonder if I’m scanning the wrong side. Here are some examples.

One of the many charms of working with vernacular photograph collections—that is, photos that were not intended as fine art—is that they come with their own special kind of provenance. I do not refer to any folder full of certificates indicating dates of purchase and previous owners, but to the history that is conveyed physically on the surfaces of a photograph whose owners never expected it might hang in a museum someday. The result of this sort of treatment, if occasionally a little cringe-worthy from a conservator’s perspective, is a rich source of narrative and culture from a historian’s. Most of these photographs have been handled, scrapbooked, lost, found, framed, passed around at parties, and generally enjoyed before they join the JMM’s collection—and they show it. While scanning sometimes hundreds of photographs a day, I end up examining a lot of photograph backs, and sometimes I wonder if I’m scanning the wrong side. Here are some examples.

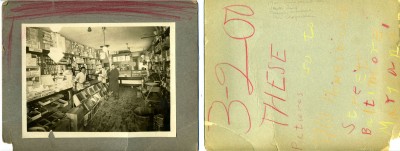

On the left is a photograph of Joseph Weiner’s first store, taken in the early 1930s; it’s a lovely example of small groceries from this period and, aside from a small tear and some marks on the supporting mat, in excellent condition for its age. But one doesn’t realize quite how special the photograph is until flipping it over. On the left is the opposite side of the mat, where a little someone with a set of crayons has made sure to include an address—in three inch characters of alternating colors for emphasis—in case the photo should ever be lost. After seeing the back, one realizes that what appears on the front as the careless, mad scribbling of a child who doesn’t know any better is in fact the mad scribbling of a child who cares very much. Not the most discreet assertion of ownership, perhaps—like I said, these discoveries do not always live up to ideal standards of conservation—but somehow a touching suggestion of a child’s attachment to a family photograph.

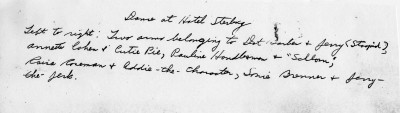

Among other signs of use and love, amateur photographs demonstrate the wonderful and all but forgotten art of the handwritten caption. Often these notes go beyond supplying names and dates and actually transform the photograph by imbuing it with a sense of original context, or the characters of its subjects. Take a look at this picture, a standard snapshot of a few girls dancing with their dates at a local sorority function:

Now take a look again, but with this handwritten note in mind:

The note reads: “Dance at Hotel Sterling/Left to right: two arms belonging to Dot Barber and Jerry (Stoopid), Annette Cohen and Cutie Pie, Pauline Hondlesman and “Schlom,” Raisa Roseman and Eddie-the-Character, Sonie Brenner and Jerry-the-Jerk.

Observe, first of all, that the memory of the fastidious author of this note is sharp enough not only to identify the gloved elbow (just entering the frame on the far left) but its owner’s dancing partner—the alluring “Jerry Stoopid,” who was unfairly rejected by the photographer’s lens. For me, this is an example of a near perfect caption, supplementing both the story—the girls giggling together later that night, making up nicknames for the boys they had danced with—and the mystery.

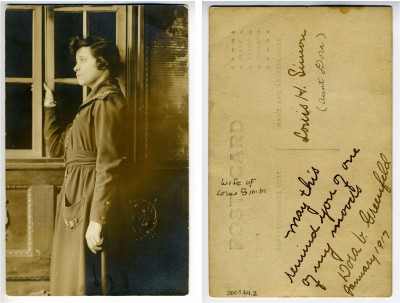

I think the most interesting reflections occur when the subject of the photograph and the author of the note are one in the same. Here is a picture postcard sent from Dora Greenfeld to her husband in January of 1917.

Dora, captured in profile, is beautiful and striking, gazing wistfully out a window with a kind of calm resolve in her expression. The depth of this personality is compounded by the message on the back of the postcard, lending a playful intimacy to the communication, and a touch of irony to the drama of her pose in the photo: “May this remind you of one of my moods.”

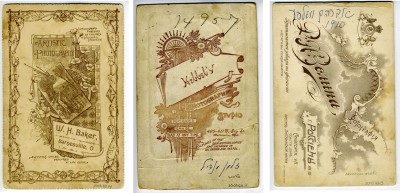

Finally, since I’m on the subject of the backs of photographs, I have to give a few examples of the backs of early twentieth century professional portraits, where studios printed beautiful advertisements:

A blog post by intern Mary Dwan.