To accession, or not to accession?

A blog post by Kierra Foley, Collections Wintern ‘12

As the JMM’s new Collections Wintern, I’ve spent a great deal of time in the depths of the basement – a land of innumerable surprises, to say the least. In recent weeks, I have found myself lost in a maze of uber organized mishegas, wandering amongst shelf after shelf (all of which are lined with massive amounts of, well, stuff). Lost in the catacombs of an American history buff’s dreams, I’ve been living at the mercy of domino effect discoveries. Each accession’s story leads me to another, revealing quite an entangled web of histories woven between these storage shelves.

Now, to give you some background about myself, I am a sophomore at Johns Hopkins University, majoring in Near Eastern Studies (with a focus on Egyptian archaeology and philology) and minoring in Jewish Studies and Classics. I’m no stranger to collections, as I also work with the collections at the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum. However, I was a complete and total stranger to working with artifacts like some of the ones I’ve processed in the past three weeks.

Why on Earth am I housing a…soy… sauce…packet? Thoughts in this vein have frequently crossed my mind.

Though, the more I explore this basement, the more a cohesive picture of Jewish culture in Maryland becomes apparent to me. I’ve become familiar with more than several families through the material culture they’ve gifted to us. The more time I spend in this basement, the more both individual personalities and collective cultural identities are becoming exceedingly evident. For this, I’ve come to realize that it’s foolish to dismiss accessioning a soy sauce packet. That packet is a very small (albeit, widely representational) piece of American Jewish culture and its connection to a Maryland family gives it a precious individual story. It’s been humbling to work with these particular collections; I’ve come to learn the value of modern historical preservation for both “scientific” anthropological documentation and attaining a deeper personal understanding of local color and heritage. In many ways, the work I’ve done here is both academic and highly personal, something that I cannot necessarily say of the antiquated artifacts that I’ve previously cataloged.

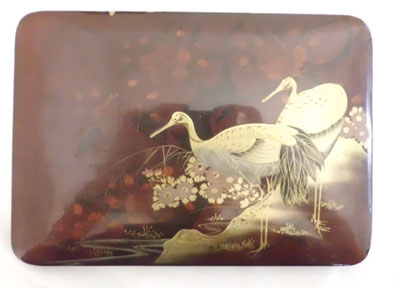

One seemingly innocuous object that revealed a much deeper and significantly more layered story is this small water fowl adorned box.

Now, as exciting as golden water fowl may be, they are not why I found this box remarkable. This box belonged to the Beissinger family, and it contained a plethora of letters and photographs pertaining directly to the life of Eric Beissinger. Upon opening the box, I was overwhelmed by a sea of German words in a tight arching script. Though my German is admittedly sub-par, I was still able to learn quite a lot about the life of this individual. Eric left war-torn Nazi Germany and his family in 1938 in favor of American soil at the astoundingly young age of twelve. His parents and brother were able to join later in time, but what is truly interesting is what is revealed about Eric’s life during this time through his letter correspondences with his German family. Eric continued to pursue his education, ultimately graduating from Johns Hopkins University in 1952.

Naturally, I grew up reading textbooks and novels about Nazi Germany, but such an intimate view into the mind of a refugee (especially one that ultimately graduated from the very school which I attend!) was never before offered to me. To learn about this world from the pen of a twelve-year-old boy is an irreplaceable opportunity, providing a much more authentic cultural picture than a textbook ever could. The accessions given to us by Eric’s wife, Claire, are invaluable for the first person picture they paint through a myriad of letters, postcards, trinkets, and photographs. Curiosity sparked by these accessions led me to explore the 2004 Lives Lost, Lives Found exhibition files (an exhibition about the lives of German Jewish refugees that found refuge in Baltimore from 1933 – 1945). Eric’s story exposed me to about twenty similar ones and I found myself totally immersed in these as well. The individuals can be woven together to reveal a larger and more powerful story – just as the artifacts in this basement show a greater picture of Jewish history.

As is probably evident by this post, I’m learning vast amounts of priceless information about history, collections, and anthropology. However, perhaps the most important lesson I’ve gleaned thus far is “never judge a box by its water fowl”.