Troubled History

A blog post by JMM Executive Director Marvin Pinkert. To read more posts from Marvin click HERE.

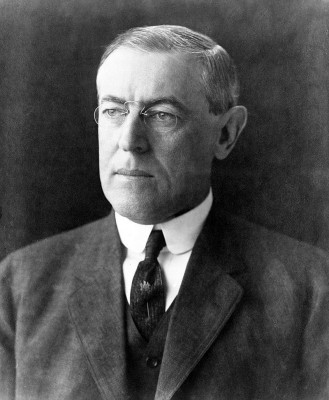

It’s President’s Day again. You may recall that last year I wrote a post on James Madison and American Jews. This year I am going to share a few thoughts about Woodrow Wilson. It seems like a timely choice: 1) This year marks Wilson’s 160th birthday; 2) In a presidential contest marked by questions of “who is a genuine progressive?” and “who is the ‘outsider’ candidate?”, Wilson is arguably a poster child for both; but perhaps most importantly 3) Wilson has become the focal point of a debate about how we treat the ugly pieces of our history and how we balance honor and ignominy in a pluralistic society. In fact the Wilson Legacy Review Committee will be holding an open forum this Friday afternoon as part of its historical assessment of our only president to have worked as a professional historian.

There seems to be a broad consensus that Wilson was among the most philo-Semitic leaders in American history. The list of tributes recorded by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency on his passing in 1924 gives some flavor of the contemporary Jewish community’s esteem (view here). Wilson is lauded his nominations of Louis Brandeis to the Supreme Court and Bernard Baruch to chair the War Industries Board., for his support of the Balfour Declaration and his three vetoes of bills that would have restricted immigration from Eastern Europe. It is no exaggeration to say that there are some American Jewish families who owe their very existence to Wilson’s actions – considering what was likely to have happened to those unable to immigrate.

So how do we square this courageous Woodrow Wilson with the Woodrow Wilson who appointed overtly racist cronies to key government offices, presiding over the re-segregation of the federal workplace.; the president who dramatically reduced the number of African American appointees to positions of government authority and who waited to the sixth year of his presidency to finally speak out against the growing wave of lynchings across the South that coincided with his term in office.

Wilson himself asserted that his policies were for “the benefit” of black people. His argument for the segregation of peoples was clothed in the language of “administrative science” as a method of reducing friction in the workplace. One suspects that his underlying attitudes are more easily understood as a product of his upbringing in Virginia, Georgia, and the Carolinas and his deep-seated belief that Reconstruction was an evil perpetuated on the South. Wilson was certainly not the only academic of his age to put a scientific veneer on his cultural prejudices (more about that in the eugenics section of our upcoming exhibit Beyond Chicken Soup: Jews and Medicine in America). Wilson was however the only academic to also be president of the United States – so his veneer proved much more harmful.

Wilson was not beyond making disparaging remarks about Jews and other immigrants and had no problem encouraging Henry Ford to pursue a career in politics, but he was not burdened with a similar core ideology about the suitability of the Jewish community (at least the assimilated Jewish community) for full participation in American life. And it seems that some of his Jewish advisors may have actually shared his views on Reconstruction and the “Lost Cause” of Southern independence. Bernard Baruch, son of a Confederate doctor, endowed the United Daughters of the Confederacy and supported their publications.

Some students at Princeton have made a case that Wilson’s failings generate uncomfortable feelings for those who study in the “Wilson School” or live in a “Wilson Dorm” and have argued for the removal of Wilson’s name from the campus. I would encourage readers of this blog post to look at the comments of scholars and biographers on this topic.

I wonder if erasing names is really the best solution to our troubled history. It leaves us in the awkward position of having only heroes and villains, rather than real human history – as messy as it is. I do not advocate giving Wilson a “pass”, but simply think it would be more effective to remember the name – but to acknowledge both good and bad associations.

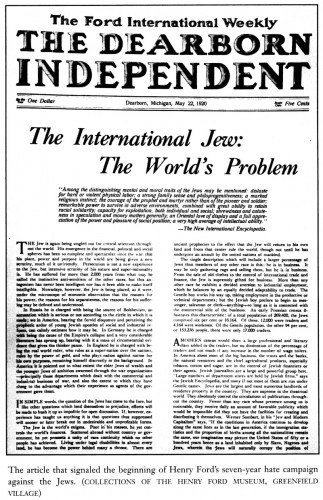

It is a principle I can live with even when the shoe is on the other foot. Two years ago I visited the Henry Ford Museum – an institution I much admire for the quality of its exhibits, although I admit a fair amount of personal distress walking into an institution named for the most notorious anti-Semite in American history. At the Museum you can visit the Ford Home and the Ford Factory, but I didn’t see a single panel on “The Dearborn Independent.”

Yet if I could make a change, it would not be to remove Ford’s name from the front door, it would rather be that somewhere in the 12 acre site there might be room to remember the damage inflicted by his baseless accusations rather than simply praise for his contributions to our industrial economy. If we erase the names of all the flawed human beings, all of our institutions will need to become “anonymous”.