Unexpected Finds: The Story of Reproductive Health in 1900s Baltimore

Penicillin’s discovery in 1928 revolutionized the treatment of many types of illnesses and infections. It also became a fixture in the treatment of venereal disease, the specialty of Dr. Morris Abramovitz, but I was surprised to not even find mention of it in the process of unpacking and photographing the contents of his doctor’s cabinet. A bit of research revealed that Dr. Abramovitz was born in 1879 and died in 1951, only a decade after mass production of the drug began. Much of Dr. Abramovitz’s work came before this medical innovation, but he still has several inventions of his own.

Penicillin’s discovery in 1928 revolutionized the treatment of many types of illnesses and infections. It also became a fixture in the treatment of venereal disease, the specialty of Dr. Morris Abramovitz, but I was surprised to not even find mention of it in the process of unpacking and photographing the contents of his doctor’s cabinet. A bit of research revealed that Dr. Abramovitz was born in 1879 and died in 1951, only a decade after mass production of the drug began. Much of Dr. Abramovitz’s work came before this medical innovation, but he still has several inventions of his own.

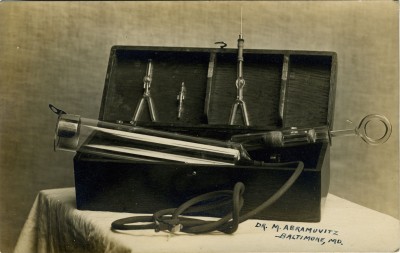

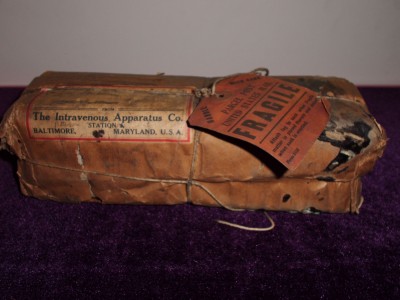

His most popular and influential invention seems to be the Combined Method Apparatus. Images demonstrating its use are featured prominently in the photos that came with the cabinet, and inside the cabinet is also a package containing the apparatus set to be mailed as far away as Indiana.

The apparatus appears to offer doctors the option to inject more than one solution at a time, in cases where combined medications or multiple treatments were required. Compared to the large hypodermic needles throughout the rest of the kit, this method appears much easier than trying to prepare two of those at once!

As opposed to curing venereal disease with huge hypodermic needles, the brighter side of reproductive health is, of course, ensuring a healthy childbirth for both the mother and baby. The same day as I wrapped up work on unpacking and photographing the doctor’s cabinet, I ended up doing image research for a Gil Sandler column about early 1900s midwives. In the article it states that in the 1920s, only 22% of births in Baltimore took place in a hospital. Among the Jewish community, many of whom were immigrants, the percentage was even lower. These immigrants were not yet comfortable with the environment of the hospital, or the all-male staff of doctors, and instead preferred the help of midwives while delivering their children at home.

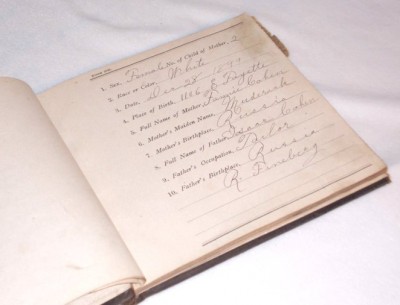

Rosa Fineberg, who worked from 1895 to 1919, had a particularly impressive record, delivering over 2,000 babies in the immigrant communities of Baltimore. The JMM was lucky to receive all of her records of her work as a midwife. The books that make up these records vary in condition, but they are all filled in by hand, recording the child’s place of birth, parents, father’s occupation, mother’s maiden name, and even how many children the couple had, all valuable information for creating a greater understanding of immigrant families in Baltimore, but also an indicator of one woman’s thorough and compassionate work as a midwife, serving the immigrant community and aiding in their transition from Europe to Baltimore.

To me, these sort of interesting, unexpected finds remind me why I find museums so interesting. In objects and photos from the past we are not only reminded of facts we already know. We also stand to be surprised by details we may not have thought of before!

A blog post by intern Emilie Reed.