Unorthodox: The Series – A Review and Conversation

This review includes descriptions of scenes from the series, which may contain spoilers for some viewers. From Visitor Services Coordinator Talia Makowsky. To read more posts from Talia, click here.

Recently, I watched the four-part series, Unorthodox, on Netflix. The show, inspired by Deborah Feldman’s memoir Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots, explores Esther’s, or Esty as she is called by most, journey from a teenager to her breaking with her ultra-religious community. This series was created by Anna Winger and Alexa Karolinski. The show draws on the source material but departs far from the actual events of Feldman’s life, though Feldman acted as a consultant to the series and even appears in it for a moment. Instead of following Feldman’s trajectory, as she took small steps away from her community over time, Esty makes a dramatic break with her family, friends, and husband, to travel to Berlin. She is forced to overcome culture shock and her own biases about the world, in order to find independence and freedom.

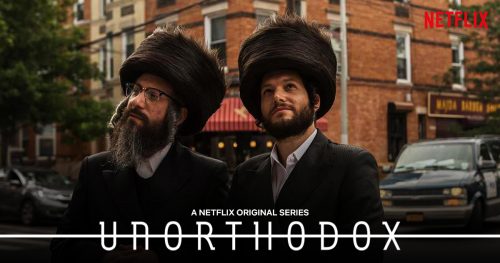

The series situates its viewpoint within Esty’s Hasidic world, specifically within the Satmar Hasidic community, based in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. There have been various challenges to Feldman’s novel and to the series itself on the apparent accuracy of the depictions of this insular, closed-off community. However, whether the way people act, dress, and speak in the show is 100% accurate or not, the showrunners deliberately found ways to contrast these Hasidic community with Esty’s new world, and these comparisons make for a fascinating study about Jewish identity, personal identity, and the role of women within such a community.

The show follows Esty’s journey out of the community, but it also includes many moments from the past, focusing on her relationship with her husband, Yanky. Through him and his naivete, he shows how women in his world are defined, through their roles as wives, mothers, and daughters. Throughout the series, Yanky’s fundamental lack of knowledge of his wife, and the way he refuses to even make eye contact with other women, is contrasted with his reverence for his mother. His strongest relationship is with his mother, the only woman, it seems he recognizes has a voice and an opinion. He is guided by her, demonstrating the influence a woman can have on the family. But when it comes to his own wife, he seems unable to recognize her as a person, only as a vessel through which to propagate, and even threatens Esty with divorce when it’s clear she’s having trouble living up to that role of wife and mother.

As young woman Esty wants to cast herself in these roles. She has a confrontation with her own mother at one point, who has left the community to live in Berlin, and telling her that she will become a good wife and mother. Esty wants to define herself through her connections with others, through the ruling of her husband, and refuses her mother’s offer of help out of these predetermined roles. However, as Yanky becomes more frustrated that he and Esty are unable to have intercourse, Esty becomes more overwhelmed with how her relationship is the talk of his family, of his mother. She has no privacy and no personhood beyond her failures. His threat to divorce her, along with the possibility that she may have become pregnant, are enough to push her out the door, away from Williamsburg, and way from the security of defined roles in the community.

As Esty struggles to find independence, adrift from her community, her views of Jewish identity are also challenged. She finds friends within a music conservatory, drawn to their performance, and soon finds out that they are from all over the world. The showrunners made sure to include characters to directly oppose the beliefs that Esty has been taught in her community, including a queer couple and an Israeli woman, Yael. Yael, in a stereotypically Israeli way, confront Esty multiple times and acts as the ambassador between Esty’s Jewish identity and the rest of the group. At one point, when they don’t think Esty is in the room, Yael even says that the women in Ultraorthodox Jewish communities, like Esty’s, are “baby machines.” Esty interrupts the conversation to say, “I am not a baby machine.”

As Esty learns more about Berlin, she continues to confront her Jewish identity. Berlin acts as a strange intersection of highly modern sensibilities (in fact, in almost every wide shot of Esty moving through Berlin there seems to be a couple kissing) and terrible history. During the group’s visit to a local lake, Esty finds out that a villa nearby was where the Nazi conference took place where they decided on the Final Solution. Esty is horrified, but her friend, Robert says “well the lake is just a lake,” and heads into the water.

For Esty, the Holocaust colors a lot of the decisions of her life as a Jewish person. Reb Joel Teitelbaum, who established the Williamsburg community and led the Satmar Jews in his lifetime, saw Zionism as a sin against God, according to biblical oaths that the children of Israel shall not go to their land before redemption. This heresy, to establish a Jewish state before the coming of the Messiah, along with assimilation, earned the Jewish people punishment, which came in the form of the Holocaust. In order to try and prevent it from happening again, and to encourage the Messiah to redeem them, Satmar Jews lead extremely observant lives, and work to “replace” those lost in the Holocaust. That is, they have children in order to make up for the lives lost during that time. (To hear more about Feldman’s personally experiences growing up with this constant knowledge and fear of the Holocaust, I recommend this interview with DW, a German public broadcast service.) Esty expresses this belief when she talks to the doctor about options for her pregnancy. Esty says she cannot get rid of the baby, as it represents so much more than just her child, but her whole, lost, ancestry.

Jewish identity in this series is not flat, but rather multi-dimensional. There are Satmar Jews who follow laws to the letter, who see their role in the strict laws and find guidance in them. There is Moishe, Yanky’s cousin, who has recently come back to the Satmar community, but we soon find out that he follows a “different Torah on the road,” as he and Yanky search for Esty. Yael, the Israeli, is Jewish, but is Esty’s complete opposite, physically, verbally, and emotionally. As for Esty, she has to figure out how she sees herself as a Jewish person, in this new/old city, and this search brings her home to her mother and allows her to find her own voice.

In the end, Esty auditions for the music conservatory, first singing an opera song her grandmother loved, which reminded her grandmother of her lost family members during the Holocaust. Esty uses this performance as an opportunity to pay homage to her grandmother, but the panel of people watching her sing ask her to choose another song better suited to her register. She is forced to figure out her own voice in a split second, something she’s been trying to do this whole time. In a bit of a shocking move, Esty chooses a song in Yiddish, a song that she would never have been allowed to sing out loud in her community, as it would have been seen as seducing the men. Now, on stage, separated from her community by miles and an ocean, she finds a way to connect to that Jewish aspect of her identity in an authentic and beautiful way. Her singing is passionate and it’s clear that everyone in the room, the panelist, her friends, her mother, and even her husband, are amazed that this voice could come out of her.

In the end, Esty does not have to throw away all the old parts of herself. Even while the community tried to break her, through Yanky and Moishe and all the stories she learned as a child, she ended up forging herself anew, supported by her new friends and her mother. Esty’s journey is astounding to watch, and all the ways the showrunners chose to interpose her current life with her old one made for a very intelligent and worthwhile series. I highly recommend the series to anyone interested in a short drama piece, especially those who have some knowledge or interest of Hasidic Judaism.