Was Our 27th President Antisemitic?

A blog post by JMM Executive Director Marvin Pinkert. You can read more posts by Marvin here.

People who follow this blog post know that I usually do a posting each year about a U.S. president and their relationship to the Jewish community. Recent examples include Teddy Roosevelt, Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy. While I remember doing one on James Madison and another on Woodrow Wilson, most of our first 25 presidents have little contact with Jewish people until adulthood. Until the 20th century all of our presidents grew up in rural areas… even John Adams lived on a farm in Braintree until the time he entered college at Harvard at age 16.

I went on a search for the first US president to grow up in a city, reasoning that he would be likely to have had more contact with the Jewish community in his childhood. I quickly found William Howard Taft, 27th President of the US. Most of us, if we remember Taft at all, remember him for his girth…the only resident of the White House to top 300 pounds. But born and raised in Cincinnati, he is also the first truly urban President.

According to jewishpress.com, Taft attended a Unitarian church that happened to be located across the street from the Plum Street Temple, presided over by Isaac Mayer Wise, the most preeminent Reform rabbi of his era. Indeed, it appears that Rabbi Wise entered into an interchange with the Unitarian minister, making Taft the first future President to have listened to a rabbi’s sermons in his youth (the article in jewishpress.com goes on to point out that in later years, Taft would comment on how impressed he was with Wise’s lectures).

Just a few months after Taft is inaugurated in 1909, he becomes the first sitting President to speak at a regular Shabbat service (at Rodef Shalom in Pittsburgh). Taft was well-regarded for keeping America open to immigrants despite a rising tide of nativist sentiment. He was awarded a medal by B’nai Brith for his “service to the Jewish race,” especially for his decision to abrogate a commercial treaty with Russia due to Russia’s policy of banning visits by American citizens of the Jewish faith.

With all this said, it is more than a little surprising that a Google search of “William Howard Taft” and “Jewish” yields results like “Anti-Semitic Taft Letter to be Auctioned” and “A Massively Anti-Semitic Letter Sent by William Howard Taft”. The flurry of articles in the Jewish press and elsewhere turns out to be inspired by the decision of the Nate D. Sanders auction house auction to put a four-page screed by Taft from 1916 opposing the appointment of Louis D. Brandeis to the Supreme Court. To put it in context, the letter is written to Gus Karger, a Jewish journalist whom Taft is friendly with. Much of the language in the letter lives up to its billing, he references Jewish “clannishness” and calls Brandeis “cunning,” a “hypocrite,” and “a power for evil”. In the end the auction house failed to get its minimum $15,000 bid for the document despite all the free publicity.

Reading through a few complete passages in the letter, I came away with a more nuanced impression of its content. It becomes clear that however inept and inappropriate his expression, Taft’s motivation is to get his friend to denounce Brandeis from within the Jewish community. He is trying to suggest that Brandeis is a radical and should not be automatically embraced by his co-religionists.

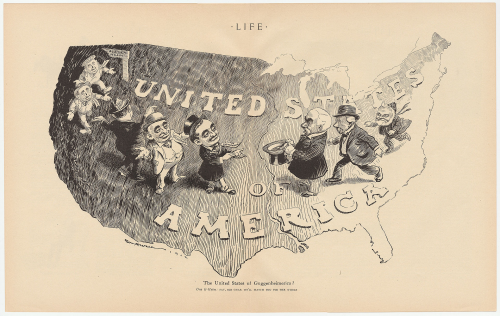

And where did Taft’s animus for Brandeis come from? It turns out that Brandeis played a small but significant role in making Taft a one-term president. This involves something known as the Ballinger Affair…let me try to break this down as best as I understand it. In spite of promises to continue Teddy Roosevelt’s legacy of the conservation of public lands, Taft appointed former Seattle mayor, Richard Ballinger to be Secretary of Interior. Ballinger set about re-privatizing public lands. This raised the ire of progressives who set about publicly denouncing Taft, including in testimony before Congress by Roosevelts close friend and holdover from his administration, conservation pioneer Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot cannot show that Taft was breaking any law, but highlighted a potential abuse of power in using his office to solicit financial support from prominent mining and logging interests. In the magazines the headlines read “Are the Guggenheim’s in charge of the Department of Interior?”

Taft/Ballinger end up firing the leading progressives in their administration, including Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot secures Louis Brandeis as his attorney for a hearing in Congress about his firing. Brandeis is able to prove that the President backdated memos he claimed he had reviewed before firing Pinchot. At that time, the President being caught lying to the American people was such a scandal that Taft’s Republicans were trounced in the 1910 election and the treatment of Pinchot so angered Teddy Roosevelt that he decided to come out of retirement and run against Taft in 1912, splitting the Republican Party and guaranteeing the election of Woodrow Wilson.