When You’re Super, the Whole World is Jewish

A blog post by Dr. Arnold T. Blumberg*

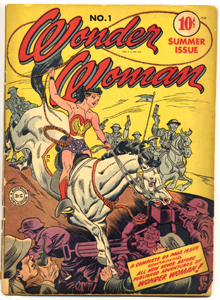

The impact of the Jewish experience on the birth of the comic book superhero genre in this country can be traced back to the heady days of the so-called “Golden Age,” when so many Jewish comics creators labored in what was the publishing equivalent of the “rag trade,” toiling at art tables to create characters from scratch, compose exciting adventures, and providing pages to publishers eager to fill the newsstands with ten-cent pamphlets that would entice kids to buy them month after month. Men like Will Eisner, Joe Simon, Jack Kirby (Jacob Kurtzberg), Jerry Siegel, Joe Shuster, Bob Kane (Kahn), Bill Finger, Jerry Robinson, Stan Lee (Stanley Martin Lieber), and so many others created a world of superheroes that for more than seventy years have spoken to Americans across the nation and fans around the globe.

The Superman character that for all intents and purposes introduced the world to the concept of the superhero has been perhaps most effectively mined for Jewish content. Conceived by two teenagers from Cleveland, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, and debuted in Action Comics #1 in June, 1938, Superman almost didn’t see the light of day. What Siegel and Shuster really wanted was to break into newspaper comic strips, a world dominated by Gentile creators and virtually closed to Jews. Their strip ideas were repeatedly rejected and their comic strip pitch for Superman was left in an editor’s desk drawer until the editors were searching for one more feature to complete the first issue of Action Comics. Pulling Siegel and Shuster’s work out of the drawer, this time the editors liked what they saw and Superman debuted as a cover story. Superman’s high-flying success turned him almost overnight into a multimedia sensation with radio, film serials, and—yes—a newspaper comic strip, and led to the introduction of countless other heroes, many of whom are little remembered today. Those characters that stood the test of time—Superman himself, Batman, Captain America, and others—have become the blockbuster movie stars of the 21st century.

Scholars interpret Superman as an immigrant, sent from a doomed planet and adopted by human parents in Kansas. Raised in heartland America, this alien with super-human powers assimilates into American culture by adopting an unassuming, rather nebbishy persona complete with suit and glasses, but remains an ex-Kryptonian who feels he must honor and protect his adopted home. Found within Superman’s basic premise is the story of the Jewish immigrants who, feeling alien upon arrival on American shores, looked for ways to “blend in” (note the many comics creators who themselves changed their names for professional or personal reasons) and ways to “give back.” Superman’s origin story has often been interpreted as a Christ allegory—Jor-El sends his one son to Earth to save us all, and in many versions he even “dies for our sins”—but in Siegel and Shuster’s original conception, he is clearly Moses, bundled into a rocket, instead of a basket, and sent off to an uncertain future.

Superman’s story also parallels the Jewish legend of the Golem of Prague. Created to be a protector for the Jews, the Golem was a clay figure who was animated through the Hebrew word for “truth” that was inscribed (often) on his forehead. Siegel and Shuster created their own Golem, and although he did not carry the word “truth” on his forehead, he did dedicate himself to “truth, justice, and the American way” while wearing an inscribed “S” on his chest. Siegel? Shuster? Superman? Savior? Perhaps all of those and more. In a coincidental but intriguing side note, nearly all the major DC Comics logos that ran at the top of every issue’s cover, including those for Action Comics and Superman, were crafted by in-house graphic designer Ira Schnapp, whose family had been stone cutters in the “old country.” Like the craftsmen who might have etched “Truth” into a Golem’s form, Schnapp was continuing the family tradition by inscribing the definitive versions of characters’ names into the covers of comic books.

I’m one of many comic book historians who have pointed out the somewhat perverse but undeniable truth that World War II was a boon to the comic book industry in general and superheroes specifically. At a time when the country was not yet at war, many of these Jewish creators were commenting on the crisis overseas, perhaps nowhere more obviously than in the cover of Captain America Comics #1 from March 1941, which features Cap punching Hitler in the face. By the time America was officially in the war, superheroes were the perfect propaganda conduit for assuring children (and plenty parents as well) that good would triumph over evil. Superheroes were seen battling the Axis, planting victory gardens, promoting the Red Cross and war bonds, and instructing kids about how to collect scrap paper for the war effort.

There’s an oft-told story that, for many, sums up the essence of pure creation and dedication that typifies comics’ Golden Age and was immortalized in Michael Chabon’s fictionalized account of the era, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (Random House, 2000). After the successful publication of Daredevil Comics #1 (often known as Daredevil Battles Hitler), the publisher had booked time on a printing press —precious during an era of shortages—to produce Daredevil Comics #2. It was Friday, and the comic had to be printed Monday. The Eisner/Iger shop, one of the key production houses providing comics material, gathered everyone they could into a New York City apartment and set them to the task, and then a blizzard hit. For that weekend, everyone worked at the top of their game; poor Bernie Klein drew the short straw and was sent out in the snow to bring back food for the group; some feared he was lost until he came back with raw eggs. Pulling bathroom tiles off the wall to use as hot plates, they set about heating the eggs, kept drawing and writing, and by Monday they had a comic book. While some of this anecdote may be apocryphal, it has passed into comics legend.

Even many years later, characters created during the Silver Age of comic books—such as Marvel’s X-Men, Spider-Man, and the Thing from the Fantastic Four by Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, and Steve Ditko—speak to aspects of the Jewish experience (The Thing was expressly identified as a Jewish character decades after his introduction). Superheroes and Jewish traditions are interwoven throughout comics history.

Comics creators brought their Jewish heritage and traditions to the page, most often unconsciously, and by virtue of who they were and when they lived, but it is important to recognize that their characters spoke (and continue to speak) to universal values. Jew and Gentile, millions upon millions of fans have embraced the hope and joy and freedom that these superheroes represent, and they stand as one of the great, lasting contributions to pop culture by Jewish artists and writers who— only trying to make a living—breathed life into paper and ink.

*DR. ARNOLD T. BLUMBERG is an author, editor, book designer, educator, and comic book historian with decades of experience in the industry. He served as Editor of The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide for many years, helped to develop some of the labels and historical designations now used widely by collectors to define eras of comic book history, covered the comic book world for numerous print and online publications, curated a pop culture/comic book museum for five years, and teaches a course in Comic Book Literature at the University of Maryland Baltimore County. He is internationally known for his University of Baltimore course, Zombies in Popular Media, co-authored Zombiemania: 80 Movies to Die For, contributed to Triumph of the Walking Dead, Braaaiiinnnsss!: From Academics to Zombies, The Undead and Theology (in which he wrote about the Jewish legend of the Golem), and the Doctor Who: Short Trips series, and writes regularly for IGN.com and AssignmentX.com. He also teaches courses in science fiction and other media, and has launched his own small press publishing company, ATB Publishing (www.atbpublishing.com).