President’s Day

A blog post by Executive Director Marvin Pinkert. To read more posts from Marvin click HERE.

Today is President’s Day. A day usually celebrated with a sale on linens. But I’ve decided to start a new JMM tradition and devote a blog post each President’s Day to the relationship between the Jewish community and one of our 44 Chief Executives.

Now the story of these relations is often fairly well documented. There are whole books on the relationship of Lincoln, Grant or FDR and their Jewish constituents. I though I might cover some of the less well known connections.

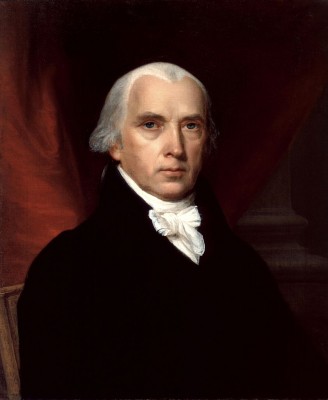

But where to begin? Since Wednesday is the bicentennial of the ratification of the Treaty of Ghent and end to the War of 1812 (known by its critics as Mr. Madison’s War), I thought that James Madison, Jr. – our 4th President was a great place to start. I found a couple of great connections between Madison and Mendes Cohen! So the subject was irresistible.

Early Years

Madison was a diminutive figure (at 5′ 4″, our shortest president) whose incredible accomplishments (“Father of the Constitution”, “Father of the Bill of Rights”) cast a long shadow on our history. In my quick research for this blog post I was not able to discover Madison’s first encounter with a member of the Jewish community but I do know when he first learned Hebrew. Yes, Madison is the first president of the United States to both speak and read Hebrew. He graduates Princeton in 1771, at age 20, but stays on for a year to study Hebrew language with the president of the university, Rev. John Witherspoon.

We also know that sometime during the revolutionary period Madison receives a loan of $50 from Jacob Cohen, Mendes’ uncle who lived in Richmond. Though his father was a tobacco planter who would eventually become the largest landowner in Orange County, Virginia, Madison himself seems to have had precarious finances prior to the death of his father in 1801. When Madison serves as a young member of Congress in the early 1780s, he appears to have been dependent on his salary. One problem – Congress has no funds to pay salaries. So they ask revolutionary war funder Haym Salomon to advance the salaries of Madison and two other members of Congress. Technically this was a loan. But in his writings, Madison tells us that Salomon refused to accept repayment. I suspect that Salomon’s generosity made a lasting impression on Madison’s assessment of the character of Jewish people.

Religious Freedom

Madison is a tireless advocate of the cause of religious freedom in America. As early as the Boston Tea Party in 1774, Madison writes to a friend that American has avoided “slavery and subjection” thanks largely to the fact that the Church of England had failed to establish itself as the official religion of the colonies.

In 1785 there is an attempt to help fund Virginia’s coffers with a tax on religious dissenters. Madison writes a “Memorial and Remonstrance” against the tax. He wrote, “The religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate. This right is in its nature an unalienable right.”

The following year, Madison introduces Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom into the state legislature. This historic document, attributed to Thomas Jefferson, but championed by Madison, lays out such a clear concept of religious liberty. Madison fought an attempt to amend the statute so that it only applied to followers of “Jesus Christ”. In Jefferson’s words, the statute needed to grant equal rights to “Jew and the Gentile, the Christian and Mahometan, the Hindoo, and infidel of every denomination.”

Three years later Madison had the opportunity to take his ideas to a national scale as he introduced the first proposal for amending the Constitution to incorporate freedom of religion. Here is Madison’s language from June 8, 1789:

Fourthly. That in article 1st, section 9, between clauses 3 and 4, be inserted these clauses, to wit: The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext, infringed.

Compare Madison’s expansive clause with the actual final language of the first amendment. How might our history of struggle for religious liberty have changed if Madison’s broader concept of civil rights had been adopted?

Madison and Mordecai Noah

The other significant connection between Madison and the Jewish community dates to his period as president. As the war with Britain approached, Mordecai Noah, an aspiring lawyer, journalist and politician in Charleston, SC came to the attention of the Madison administration through a series of articles he wrote in support of resistance to British aggression. This was a minority point of view in Charleston and, according to historian Simon Wolf, Noah’s life was threatened on multiple occasions because of his outspoken opinions.

In 1811, Madison offers Noah an appointment to be counsel in Riga, (today Latvia, then Russia). This is the first diplomatic post offered to a member of the Jewish faith – Noah turns it down. But two years later, Noah accepts an invitation to become counsel in Tunis. The most critical part of his job was negotiating with the Barbary Pirates for the release of American sailors. It turns out that Madison’s policy of paying ransom to a group we were today call terrorists may have saved many lives, but was not very popular. Secretary of State Monroe decides that the best solution is to recall Noah on the grounds that his religion offended his hosts. To add insult, Monroe claims to have been ignorant of Noah’s religion before his appointment.

It appears that Noah and the Jewish community vented their outrage on Madison. Some sources go so far as to declare this the only act of overt religious discrimination against Jews in a government appointment. Further reading convinced me that the situation is far more complex and that the role played by Monroe in the recall may be much more important than that of Madison.

In fact, Madison later writes the following to Noah:

As your foreign mission took place whilst I was in the administration it cannot be but agreeable to me to learn, that your accounts have been closed in a manner favorable to you. And I know too well the justice and candor of the present executive [Monroe] to doubt that an official preservation, will be readily allowed to explanations necessary to protect your character against the effect of any impressions whenever ascertained to be erroneous. It was certain, that your religious profession was well-known at the time you received your commission, and that in itself it could not be a motive in your recall.

Cutting through the 19th century pleasantries, I think Madison is basically laying the problem at Monroe’s doorstep.

Maryland Jew Bill and Cohens v. Virginia

Even after leaving office, Madison remains active in public life. His opinions are sought out on issues of controversy.

In 1818 advocates of the repeal of the oath to the New Testament in Maryland (the “Maryland Jew Bill”) solicited and received endorsements from all three living former presidents (Adams, Jefferson and Madison). Madison’s letter read in part:

Having ever regarded the freedom of religious opinions, and worshippers, equally, belonging to every sect, and the sure enjoyment of it, as the best human provision, for bringing all into the same way of thinking, or into that mutual charity, which is the only proper substitute, I observe with pleasure, the view you give of the spirit in which your sect partake of the common blessings, afforded by our government and laws.

No points for writing style, but the sentiment is in the right place.

In 1821 Madison is asked to comment on case of Cohens vs. Virginia. According to Kevin Gutzman in James Madison and the Making of America, his Democratic compatriots expected him to castigate Chief Justice Marshall for his aggrandizement of power in the Supreme Court. Marshall decides that the court has authority to take a case from criminal defendants – in this case Mendes and Phillip Cohen for the “crime” of selling DC lottery tickets in Virginia – when state and federal law are in conflict. Madison takes a more measured view, arguing that it would be better to pressure Congress to stop writing laws that interfere with state authority than it would be to constrain the Supreme Court in its rulings. Of course, the part that interested me is that Mendes Cohen is everywhere – even in the commentaries of James Madison.

——————–

I welcome your suggestions for which of the other 43 men we should explore next President’s Day.

~Marvin