A “Children’s Playground” and “Centre for Adults”

The Story of Baltimore’s Jewish Educational Alliance, 1909-1952

Article by Jennifer Vess. Originally published in Generations 2009-2010: 50th Anniversary Double Issue: The Search for Social Justice.

“Most of our activity when we were growing up was at the JEA. . . . We learned how to speak, we had declamation contests, we played basketball. Even I, who was like a little butterball, whenever they’d let me in the game I’d play. But I was on the team.” — Paul Wartzman, Jewish Museum of Maryland oral history

Part I: Settlement Houses

The Jewish Education Alliance is usually depicted through the eyes of childhood. Its programs influenced thousands of Jewish boys and girls in East Baltimore during the first half of the twentieth century, boys and girls who later remembered it as the place that shaped their lives, taught them skills, and gave them a way to be active without getting into serious trouble.

Few people remember the JEA as part of a nationwide settlement house movement that advocated new ways to bring social services and change to urban areas, especially to immigrant neighborhoods. The JEA offered space for clubs, entertainment, and athletics for children and teens, but it was built for more than engaging the kids of the neighborhood. It was founded as a settlement house meant to serve and uplift the immigrant Jewish community of East Baltimore.

Settlement houses first appeared in the United States in 1886, modeled after similar organizations in England. They were planned as social service and community centers in poor, often heavily immigrant areas, staffed by trained, well-educated men and women. The staff, mostly from middle class backgrounds, lived at the settlement house. Supporters believed that living in the community allowed workers to understand the true needs of the poor and create effective ways to deal with those needs by forming close relationships with the residents. Young settlement workers differed from the older generation of charity workers who often focused on the destitute rather than the working poor and who entered poor communities with preexisting ideas of the meanings of and reasons for poverty, usually focusing on individual weaknesses. This new generation wanted to launch investigations to find the deeper and broader social or economic problems that led to poverty.[1]

Settlement house workers, however, did have their own preconceived ideas. Many of them were influenced by the Progressive movement which swept the nation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Progressive reformers were diverse individuals, but a few generalizations can be made about them: they saw the basic problems around them as linked to industrialization and the growth of a multi-ethnic society, they often formed coalitions to make their reforms work within the existing political system, and they believed that with the proper environment anyone could change for the better.[2] For settlement workers, as for most reformers, a proper environment included basic education, cultural development, improved health and cleanliness, and the Americanization of immigrants.

Many Progressive reformers and settlement house workers were influenced by Protestant Christianity. But since most of the neighborhoods they targeted were religiously and ethnically diverse (and often more Catholic and Jewish than Protestant), settlement movement leaders such as Jane Addams of Hull House strove to maintain secular institutions in order to serve the entire local population. However, a number of settlement houses reached out to specific ethnic or religious communities. Jewish settlement houses appeared in cities throughout the country, set up by the Jewish community (often by American Jews of German descent), for the Jewish community (predominantly East European immigrants). They embraced many of the same goals as other settlements and offered many of the same programs. But to varying degrees, they also incorporated Jewish culture and religion into their activities.[3] The JEA of Baltimore was one of these houses.

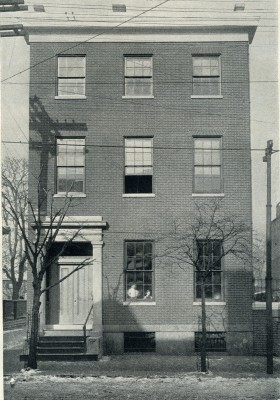

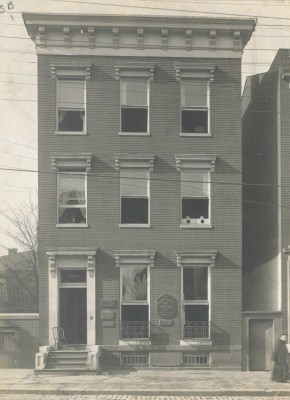

By 1909 the United States had close to 400 settlement houses, with a total of twelve in Baltimore.[4] Two of those twelve, the Daughters in Israel and the Maccabean House, served the Jewish community of East Baltimore. Women founded the Daughters in Israel in 1890 to aid immigrant girls. Along with a range of programs, they opened the Working Girls’ Home where young women with jobs, but without parents or guardians, could live. A group of men incorporated the Maccabean House in 1900 “for the purpose of maintaining a reading room and library and other educational and benevolent . . . undertakings in the city of Baltimore; [and] carrying on educational, benevolent and philanthropic work among the poor.” The Maccabean House focused on, but did not limit its activities to, the young men of East Baltimore.[5]

The two institutions had overlapping programs as well as gaps in their service to the community, so in 1909 they merged to form a new institution: the Jewish Educational Alliance.[6] Departing from the gender-segregated structure of nineteenth century charities, eight men and eight women joined together on the founding board of directors (see Caroline Friedman’s article in this issue on women’s role in charities). But the board did not depart from convention in another respect. Its members were all American-born children of German descent, drawn from long-established and well-off Jewish families: William Levy, Aaron Benesch, David Federleicht, Simon H. Stein, Walter Sondheim, Dr. Jose Hirsh, Henry S. Frank, Lewis Putzel, Laura Greif, Laura Guttmacher, Bertha Dalsheimer, Miriam Bernstein, Minnie Wiesenfeld, Lillie Strauss, Mollie Wiesenfeld and Mrs. S.B. Sonneborn.[7]

Their backgrounds contrasted with the newly-arrived East European Jews who populated the East Baltimore neighborhood where the new settlement house was located. But the mediators between the board and the neighborhood – the settlement workers who lived and worked at the JEA – were a mix of German and Russian, some children of immigrants, and others immigrants themselves.[8]

Continue to Part II: A Jewish Spirit

Notes:

[1] Allen F. Davis, Spearheads for Reform: The Social Settlements and the Progressive Movement: 1890-1914 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 18.

[2] Daniel T. Rodgers, “In Search of Progressivism,” Reviews in American History 10, No. 4 (December 1982).

[3] Mina Carson, Settlement Folk: Social Thought and the American Settlement Movement, 1885-1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago press, 1990), 53-64.; Gerald Sorin, A Time for Building: The Third Migration, 1880-1920 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992); Finding Aid, Jewish Educational Alliance Records, 1915-2008, JMS 002, Savannah Jewish Archives at georgiahistory.com/containers/99.

[4] Robert A. Woods and Albert J. Kennedy, eds., Handbook of Settlements (New York: Charities Publication Committee, 1911), 95-104.

[5] “Daughters In Israel: A New Society for Doing Good – its purpose,” Baltimore Sun, November 10, 1890, p. 6; Articles of Incorporation for The Maccabeans of Baltimore City, March 19, 1900, MS170, Folder 210, Jewish Museum of Maryland (JMM).

[6] After the merger, the Maccabean House ceased to exist. The Daughters in Israel continued to operate the Working Girls’ Home.

[7] October 21, 1909, JEA meeting minutes, MS 170, Folder 212, JMM; U.S. Census Bureau, Baltimore City Manuscript Census, 1910, 1920.

[8] U.S. Census Bureau, Baltimore City Manuscript Census, 1910, 1920.