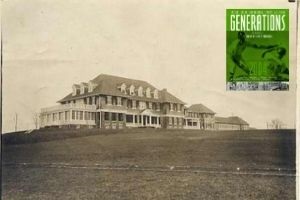

A Club of Their Own

Suburban and Woodholme Through the Years

Article by Dr. Deborah R. Weiner. Originally published in Generations – 2004: Recreation, Sports & Leisure. This particular issue of Generations proved wildly popular and is no longer available for purchase.

Article by Dr. Deborah R. Weiner. Originally published in Generations – 2004: Recreation, Sports & Leisure. This particular issue of Generations proved wildly popular and is no longer available for purchase.

Part I: Uptown and Downtown – A Little Social Background

There are two things everyone seems to know about Baltimore’s Jewish country clubs. First, wealthy Jews of German ancestry founded the Suburban Club because they could not get into non-Jewish country clubs. Second, the “German” Jews would not let the “Russian” Jews in to their club, and so the Russians started their own, the Woodholme Country Club.

Both these things happen to be true. But is that all there is to be said about the city’s two oldest Jewish country clubs? Certainly not. Suburban and Woodholme span a hefty chunk of Baltimore Jewish history. They have changed with the times, in ways that have reflected not only the development of the Jewish community, but also trends in American society. More than simply playgrounds for the privileged or icons of status, they are dynamic institutions whose story helps to tell us who we are.

That story begins more than one hundred years ago. By 1900, Baltimore’s German Jewish community was over a half-century old. Its members, many far removed from their immigrant origins, had blended in to the business and civic life of the city. Socially, however, they moved in their own separate sphere. Although Jews mixed with gentiles in fraternal clubs such as the Masons and Odd Fellows, most of their organized social activities occurred in a separate, parallel universe to non-Jews.[1]

A number of Jewish clubs met the social and recreational needs of the community, with the wealthiest and oldest-established families creating their own institutions at the pinnacle of Jewish society. These included the in-town Phoenix Club for men (founded in 1886) and the Harmony Circle debutante balls (begun in the 1860s), where “daughters of the right families could meet sons of the right families,” in author Gil Sandler’s words. Jews constructed their own social hierarchy partly because they were not welcome in gentile high society. As social leader Marie Rothschild once explained, “not being eligible for the non-Jewish Junior Assembly,” wealthy Jews “decided to have a similar set-up.”[2] But internal factors as well circumscribed the social world of upper-crust German Jewry: business and family ties, a desire for their children to marry within the Jewish faith, and affinity with people of similar background.

This affinity did not extend to the Eastern European immigrants who began to make their presence felt in the late nineteenth century. Jewish Baltimore had become socially stratified well before they appeared, but class differences among German Jews began to seem less and less relevant in the face of the social chasm that existed between the established Jewish population and the tide of foreigners whose language, customs, appearance, poverty, and even religion bore little resemblance to the American Jewish lifestyle. Now there were two Jewish communities: the “uptown” German Jews and the “downtown” Russian Jews.

Continue to Part II: A Rural Retreat

Notes:

[1] Isaac M. Fein, The Making of an American Jewish Community: The History of Baltimore Jewry from 1773 to 1920 (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1971).

[2] Gilbert Sandler, Jewish Baltimore: A Family Album (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 46-47.