A Club of Their Own Part V

Article by Dr. Deborah R. Weiner. Originally published in Generations – 2004: Recreation, Sports & Leisure. This particular issue of Generations proved wildly popular and is no longer available for purchase.

Article by Dr. Deborah R. Weiner. Originally published in Generations – 2004: Recreation, Sports & Leisure. This particular issue of Generations proved wildly popular and is no longer available for purchase.

Part V: Controversies and Changing Times

Before Glick, wives of Woodholme members didn’t play much gold, observes Sewell Sugar. Perhaps that’s because club policies toward women, as at most other clubs around the country, weren’t exactly equitable. Women became “much more a part of the club in the fifties” and continued to make gains in ensuing decades. They “had to push a little bit,” says Sugar, because most of the older people were not prone to change.” One who pushed was Lyn P. Meyerhoff, a woman who enjoyed “thumbing her nose at convention,” according to her daughter Lee. Once, Meyerhoff “did nine holes of the Woodholme Country Club golf course backward, because women were always bumped by the men for tee-off times, and she was furious at the ‘old fart’ inequity of the practice.” She also dove off the high-dive at the Woodholme pool when she was five months pregnant, “at a time when women covered their bellies behind voluminous tent dresses.” This was in the 1950s, when, it appears, the extended Meyerhoff family considerably livened things up at the club.[1]

Lyn Meyerhoff heralded a changing attitude among at least some wives of club members, who slowly began to assert themselves. Their emergence led to what members of both country clubs see as the biggest single change to take place over the years: the clubs’ policies toward children. Originally, the clubs catered strictly to adults, primarily men. Members from multi-generational Suburban Club families recall that the club was “not a child-friendly place” when they were young. Children were allowed on the grounds only during very limited hours and there were no special facilities for them. As society grew more child-centered, so did the country clubs. At Suburban, change stated with the inclusion of a Youth Room in the new clubhouse, built in 1960, and the installation of a “kiddie pool” in 1961. Hours for children slowly began to expand, and now, as Julius Westheimer notes, “it’s a family affair.” Ditto at Woodholme, which is “really a family club right now,” says Sewell Sugar.[2]

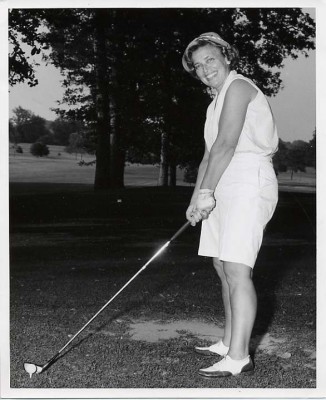

Despite the emergence of women and children, policies at Woodholme and other clubs have remained biased in favor of men in many areas. A Baltimore Sun article written during the 2003 controversy over the all-male policy at Augusta National (home of the Master’s golf tournament) revealed that Woodholme’s latest female golf standout, ten-time amateur women’s city champion and two-time state champion Andrea Kraus, was barred from teeing off until 11:30am on weekends and holidays, even though her husband Ken, “who often shoots in the triple digits,” could do so. “Country club golf certainly can be the last bastion of male chauvinism,” Kraus was quoted as saying.[3]

But things could be worse, unlike some clubs, both Woodholme and Suburban admit women to membership. (At Suburban, they had a sort of “junior” membership from the very beginning, while Woodholme admitted women to membership in later years.) After two decades of board wrangling, Suburban gave full voting rights to female members I n1988, and in 1990, “objections to sexism” caused the club to integrate its card rooms. Suburban now officially has “gender neutral” policies. Perhaps not totally out of choice, though: country clubs that benefit from a special tax break for preserving open space are legally required to be non-discriminatory. Suburban takes the tax break; Woodholme chooses not to.[4]

Of course, country clubs are famous for being bastions not only of male privilege, but also of white privilege. Suburban and Woodholme seem little different from the norm in that regard. Both have membership policies that do not officially discriminate with regard to race, religion, or gender. But the clubs have very few African American or non-Jewish members. A fascinating view of black-Jewish relations can be glimpsed in the memoir of Dewayne Wickham, an African American journalist who worked in Woodholme’s largely black caddy force in his teens during the early 1960s. Woodholme members were “not intentionally mean-spirited or racist,” but could be “condescending and patronizing in the way [of] many white liberals,” Wickham observes. Yet the club provided an anchor in his life, which had been marked by tragedy, and his affection for it shines through. He describes the generosity of many club members and the positive response of club officials to the caddies’ efforts to improve their working conditions. In his portrayal of fumbling attempts at communication across the racial divide made by caddies and members, and the shared love of golf that served as perhaps the most genuine link between the two, he captures the complexities of life in an unequal society just beginning to feel the effects of the civil rights movement.[5]

If societal change began to infiltrate the sheltered country club world of the 1950s, it started knocking loudly at the door during the turbulent years to come. Clubs fell out of favor as a result of “the new social consciousness which came out of the 1960s and which turned many people off to such status symbols as Cadillacs and country clubs.” This was the assessment of reporter Tom Nugent, whose 1977 Jewish Times exposé of Baltimore’s Jewish country clubs attempted to assess the fallout of the previous decade. To attract flagging interest, clubs had to alter their policies. “The relaxation of once-stringent dress codes; the drastic reduction of initiation fees…the liberalizing and streamlining of procedures for admission…all these things are evidence” of the transformation taking place, Nugent asserted. Worse, he noted, were “occasional incidents of shocking behavior in the club house,” including at least one instance of co-ed showering. He quoted an (anonymous) member of an (unnamed) club: “I know it must irritate the hell out of [older members] to see what’s happened in their club. They used to walk in and everything was very refined, and everything was very tastefully done – and it’s turned into Tackyville! The whole atmosphere is just completely different.”[6]

Nugent concluded, back in 1977, that country clubs faced an “uncertain future.” His informants had different views on whether or not they would even survive. “It’s all changing. It’s a way of life, really, that’s ending,” one member told him.[7]

Continue to Part VI: The View from a New Millenium

Notes:

[1] Sugar interview; Lee Meyerhoff Hendler, e-mail correspondence supplied to author, March 17, 2005.

[2] E. B. Hirsh, phone interview with author, December 2004; Morton Offit, phone interview with author, December 2004; Westheimer, Sugar, other interviews; The Suburban Club, 46.

[3] Don Markus, “Golf’s Private Policy Meets Public Debate,” Baltimore Sun, April 7, 2003, 1D.

[4] The Suburban Club, 45, 69; Woodholme Club Vertical File, JMM.

[5] Dewayne Wickham, Woodholme: A Black Man’s Story of Growing Up Alone(New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995), 219.

[6] Tom Nugent, “Some Things You Always Wanted to Know About Country Clubs, And More,” Jewish Times, October 7, 1977, 31.

[7] Nugent, “Some Things You Always Wanted to Know,” 31, 34.