A Social Strategy

Part 3 of “Dressing the Part,” written by Melissa Martens Yaverbaum, former JMM curator. Originally published in Generations – Winter 2001.

Part 3 of “Dressing the Part,” written by Melissa Martens Yaverbaum, former JMM curator. Originally published in Generations – Winter 2001.

Dressing appropriately was part of a Jewish woman’s social strategy, and a column in the Jewish Comment entitled “What She Wears” (a regular column) stressed the importance of fashion to its female readership:

The student of dress at the commencement of the season is naturally anxious to know what the prevailing styles will be…Everything that is fashionable this season will be gorgeous. The word simplicity will not be understood.[1]

Even while fashion assisted women with their assimilation into American activities, stylish clothing also played a role in the execution and re-shaping of Jewish activities. The Sabbath day, which called fo the use of ornaments and finery reserved for the day, also implied fancy dress in both the homeland and America.[2] The Jewish Comment on May 7, 1898 reported on the Jewish woman:

What a day of joy does she not make the Sabbath to her husband and children! How different it is from the other days of the week! Dressed in festive attire she herself lights the Sabbath tapers while pronouncing the benediction.[3]

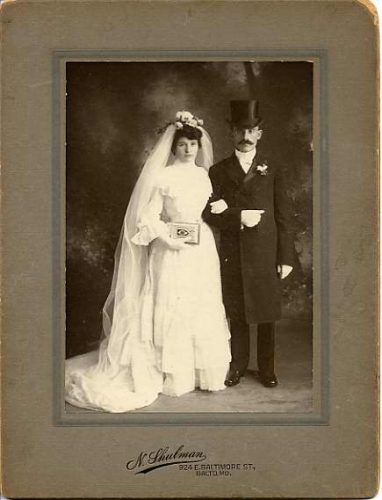

Reform Judaism, which appealed to an increasingly accultured segment of the Jewish population in Baltimore at the end of the nineteenth century, called for a new brand of respectable American dress for Sabbath and synagogue functions, both religious and social. A photograph in Isador Blum’s book, The Jews of Baltimore: An Historical Summary of Their Progress and Status as Citizens of Baltimore from Early Days to the Year Nineteen Hundred and Ten shows the exterior of Temple Oheb Shalom’s building on Eutaw place around 1910 with congregants strolling outside dressed in top hats, capes, long skirts, cinched blouses, and fancy hats.[4] Similarly, confirmations, weddings, auxiliary formals, and bar mitzvahs became occasions to participate in Jewish community and American fashion at the same time. As synagogue functions mingled with social ones, dress for Jewish activities became increasingly important. Respect and reverence were gauged, in part, by the formality of one’s presentation. Thus, the display of fancy clothing served religious and social goals at the same time.

The photograph and textile collections of the Jewish Museum of Maryland demonstrate the impact of fashionable goods on Jewish-American lifestyles. Clothing worn for synagogue activities, confirmations, bar mitzvah celebrations, weddings, Jewish business banquets, and other Jewish social events underscores their significance in Jewish life. Like the Jewish-owned department stores themselves, much of the clothing in the Jewish Museum of Maryland’s collection is clearly “American.” However, the ways in which this clothing was created, sold, utilized, valued, and maintained point to the more complex ways in which Jewish and American identities shaped each other over time. While a fancy hat may seem completely mainstream in its design, the same hat takes on new meaning when made by a Jewish manufacturer, sold in a Jewish department store, promoted in a Jewish periodical, and worn by a Jewish consumer on both religious and secular occasions.

Department stores, the styles they promoted, and the fashions they sold were vehicles for transformation and expression in Jewish Baltimore. Of the many goods the department stores sold, clothing is, perhaps, the most powerful symbol of personal and cultural identity. Regardless of background, Baltimore’s Jewish population used fashions from the department stores to define and re-define themselves. To dress American was to be American, and stylish clothing made its way into important events in Jewish-American life, infusing each occasion with national, ethnic, religious, and personal meanings.

~The End~

[1] Jewish Comment, 26 April 1895: 3.

[2] Andrew R. Heinze, Adapting to Abundance: Jewish Immigrants, Mass Consumption, and the Search for American Identity (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990) 55.

[3] Jewish Comment, 7 May 1897: 4

[4] Isador Blum, The Jews of Baltimore: An Historical Summary of Their Progress and Status as Citizens of Baltimore from Early Days to the Year Nineteen Hundred and Ten, (Baltimore: Historical Review Publishing Company, 1910) 30.