Becoming Pikesville

By Research Historian Deb Weiner

By Research Historian Deb Weiner

Last weekend I volunteered on a political campaign in the swing state to the north. As I was sitting in the campaign office in Harrisburg, another group of Baltimore volunteers walked in. One of the women looked at me and said, “You look familiar.” She looked vaguely familiar to me as well. Neither of us could figure out how we knew each other until she offered, “I’m from Pikesville.” I responded, “Oh, I work at the Jewish Museum of Maryland. Have you been there?” Turns out she used to work at the Associated Jewish Federation, and we probably met at some kind of Associated-related event.

Last weekend I volunteered on a political campaign in the swing state to the north. As I was sitting in the campaign office in Harrisburg, another group of Baltimore volunteers walked in. One of the women looked at me and said, “You look familiar.” She looked vaguely familiar to me as well. Neither of us could figure out how we knew each other until she offered, “I’m from Pikesville.” I responded, “Oh, I work at the Jewish Museum of Maryland. Have you been there?” Turns out she used to work at the Associated Jewish Federation, and we probably met at some kind of Associated-related event.

To anyone from Baltimore, my response would not seem to be a non sequitur. That’s because saying “I’m from Pikesville” is virtually a substitute for saying “I’m Jewish,” but without the awkwardness of announcing your religious identity to a (near) total stranger. The fact is, Pikesville is home to 30 percent of Baltimore-area Jews, according to the most recent Associated Population Study. Even more pertinent, around four out of five Jews live in the northwest portion of the Baltimore metro area, from Upper Park Heights to Owings Mills and beyond, in an area that might realistically be termed “Greater Pikesville.”

To anyone from Baltimore, my response would not seem to be a non sequitur. That’s because saying “I’m from Pikesville” is virtually a substitute for saying “I’m Jewish,” but without the awkwardness of announcing your religious identity to a (near) total stranger. The fact is, Pikesville is home to 30 percent of Baltimore-area Jews, according to the most recent Associated Population Study. Even more pertinent, around four out of five Jews live in the northwest portion of the Baltimore metro area, from Upper Park Heights to Owings Mills and beyond, in an area that might realistically be termed “Greater Pikesville.”

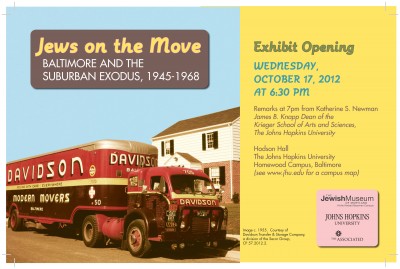

Which brings me to the subject of this blog post. Next Wednesday, October 17, we are opening the traveling exhibition “Jews on the Move: Baltimore and the Suburban Exodus, 1945 to 1968.” The exhibition reveals how and why Jews became concentrated in the metro area’s northwest suburbs in the decades after World War II. It was a process that took only a single generation to complete, but remains a powerful fact of Baltimore Jewish life today, several decades later.

Which brings me to the subject of this blog post. Next Wednesday, October 17, we are opening the traveling exhibition “Jews on the Move: Baltimore and the Suburban Exodus, 1945 to 1968.” The exhibition reveals how and why Jews became concentrated in the metro area’s northwest suburbs in the decades after World War II. It was a process that took only a single generation to complete, but remains a powerful fact of Baltimore Jewish life today, several decades later.

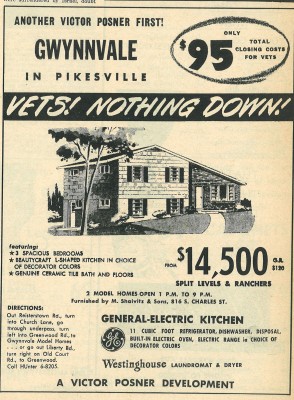

It’s a national story, but with a local twist—Baltimore Jews joined the rush to suburbia that occurred across America after World War II, but why they ended up in one particular section of the metro area is a complex tale with a lot of local nuances. Ironically, the exhibition does not really focus on Pikesville, because it wasn’t until the early 1980s that Pikesville beat out Randallstown as the suburb of choice for Jews within northwest Baltimore. What the exhibition does do is show how the “northwest exodus” became firmly established in those early years of suburbanization, leading to the settlement patterns we see today.

It’s a national story, but with a local twist—Baltimore Jews joined the rush to suburbia that occurred across America after World War II, but why they ended up in one particular section of the metro area is a complex tale with a lot of local nuances. Ironically, the exhibition does not really focus on Pikesville, because it wasn’t until the early 1980s that Pikesville beat out Randallstown as the suburb of choice for Jews within northwest Baltimore. What the exhibition does do is show how the “northwest exodus” became firmly established in those early years of suburbanization, leading to the settlement patterns we see today.

By the way, I should mention that the exhibition is opening not here at the JMM, but at Hodson Hall on the Johns Hopkins University campus, where it will be on view until December 17. We created the exhibition in partnership with students in JHU’s Museums and Society program, through a class that JMM staff taught last spring. The students were from all over (California, New York, D.C. suburbs) but by the time the semester ended they could throw around terms like “Baltimore Beltway” and “Mandell-Ballow” with ease.

By the way, I should mention that the exhibition is opening not here at the JMM, but at Hodson Hall on the Johns Hopkins University campus, where it will be on view until December 17. We created the exhibition in partnership with students in JHU’s Museums and Society program, through a class that JMM staff taught last spring. The students were from all over (California, New York, D.C. suburbs) but by the time the semester ended they could throw around terms like “Baltimore Beltway” and “Mandell-Ballow” with ease.