Dispossession and Adaptation Part III

Article written by Anita Kassof, former JMM associate director. Originally published in Generations – Winter 2002: Jewish Family History. Information on how to purchase your own copy here. Many thanks to JMM collections manager Joanna Church for re-typing this article.

Part III: The Girls Get Out

Missed the beginning? Start here.

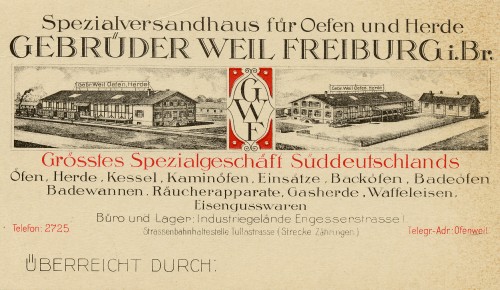

During the Hitler period, Erna, Lisa, and Toni urged their parents to apply for U.S. immigration visas. Although the Weils were well-to-do, finances proved to be the biggest stumbling block to immigration. The United States required potential immigrants to prove that they would be self-supporting or had a sponsor in the United States who would guarantee that they would not join the public relief rolls. Yet, the Nazis’ punitive taxes pauperized the Jewish emigrants, and the Weils had no close friends or wealthy relatives in the U.S. to vouch for them. Erna recalls that for years before they were able to submit their application, she and her sisters scoured American telephone directories and wrote hundreds of letters to complete strangers, asking them to sign affidavits assuring the U.S. government that they would not allow the Weils to become public charges. Finally, their persistence paid off: a New York advertising tycoon named Albert Lasker agreed to serve as their sponsor.

At the same time, the Weil family had to assemble the paperwork required to complete the application, including five copies of their U.S. visa applications, two copies of their birth certificates, and certificates of good conduct from German police authorities. Theo and Hilda included copies of their marriage license, and Theo attached copies of his military record.

Finally, in August 1938, the Weils submitted their applications to the U.S. Consulate in Stuttgart. They were extraordinarily fortunate to have applied just months before the Night of Broken Glass. After that, desperate refugees flooded the overseas consulates, and the wait for visas to the U.S. – which limited German and Austrian immigrants to 27,370 annually – stretched to years.

Although the Weils submitted their applications before the deluge, they still anticipated a lengthy wait before they were called to the consulate for a physical examination – the last hurdle they had to clear before purchasing ship tickets. A restrictionist U.S. State Department, wary of allowing a flood of immigrants to enter the country during a time of economic depression, instructed overseas consuls to examine all applications stringently, regardless of the delay that entailed. Nor did the State Department send additional consular offers to the overseas embassies and consuls to handle the backlog. As a result, even before 1938, émigrés could expect waits of several months to more than a year before receiving their visas. In the unstable, volatile atmosphere of Nazi Germany, the wait could be excruciating. It was all the more difficult for the Weils, because between the time they applied for their visas and the time they received them, the Night of Broken Glass and Theo’s ensuing arrest shattered their illusions of waiting safely in Germany.

After Theo’s arrest, Hilda masterminded a plan to free him, but it was Toni who carried it out. Just before Theo was transferred to Dachau, diminutive Toni slipped into the Freiburg prison with a bundle of papers for him. She explained to the jailors that Theo had to sign paychecks for his Jewish and non-Jewish employees. The ruse worked. Theo not only endorsed the checks, but managed to sign several blank business papers. These helped Hilda and her daughters liquidate parts of the business so they could finance legal fees and bribes. Theo’s captors agreed to his release from Dachau, but not before they gave him a bath – by turning an icy hose on him on a raw November day. After five days in Dachau, Theo returned to Freiburg a changed and damaged man. Covered from head to toe with bruises and blisters, he crawled into bed and remained there for four weeks.

As Theo recovered, the family continued to arrange for their anticipated emigration. The Weils packed four enormous lifts, each the size of a moving van, with furniture, artwork, and household goods. They forwarded their lifts to New York, hopeful that they would join their belongings there one day. The goods that the Weils shipped speak of an elegant lifestyle in an elaborate home. They include ornately carved and inlaid wooden chairs and tables, custom-made by a Swiss craftsman. Massive armoires and sideboards, heavy wooden tables and upholstered chairs, exquisite bed and table linens, fine silverware and china services for 24, and valuable paintings filled the lifts. By the time the Weils left, however, the Nazis forbade Jews to remove or transfer currency from Germany. As a result, it was not unusual for a family like the Weils to arrive in the United States accompanied by crates of belongings, but unable to afford to pay rent for an apartment to house their things.

![“Im Spielwarenladen” [In the Toy Store], one of the children's games that the Weils packed in their lifts. Its presence among the belongings they shipped – long after their daughters were grown – suggests that the Weils packed their entire household in the realization that they would never return to Germany. Courtesy of Brenda Mandel; photo by Stephen Mayer, L2002.103.4.](https://jewishmuseummd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/L2002.103.004-500x331.jpg)

Meanwhile, life in Germany grew increasingly unbearable. After November 1938, the Nazis unleashed a battery of anti-Jewish legislation: Jewish access to public areas was circumscribed; Jews had to turn over all of their gold and silver; Jewish children were expelled from schools; and Jewish businesses were “Aryanized” – turned over to non-Jewish proprietors with no compensation to their original owners. Unable to endure life in Germany, the sisters secured “domestic permits,” which enabled them to work as servants in England while they waited to receive their U.S. visas.

After a brief stopover in Switzerland, the Weil sisters arrived in rural England, where they were assigned posts as household servants. Suddenly, Erna, Lisa, and Toni, who had grown up in a house full of maids where they never so much as had to boil an egg, found themselves hauling buckets of coal to heat drafty mansions in the English countryside. “It wasn’t for us,” recalled Erna, with characteristic understatement. However, the three girls managed to adapt to new and unfamiliar circumstances. Erna and Lisa, who were in the same town, left their employers after three days. Using funds they borrowed from the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society during their stopover in Zurich, they made their way to Bournemouth in southern England, where they were reunited with Toni.

Evading employment restrictions on foreigners, Lisa found a job as a governess, caring for two small children. Erna and Toni, “little itty bitty things,” in Toni’s words, became chauffeurs. Were it not for the increasingly desperate letters the sisters received from their parents, their year in England might almost have been a pleasant interlude. Erna drove for Mrs. Jacobs, a kindly Jewish woman who had a vacation home by the sea. After she chauffeured Mrs. Jacobs to her cabana, Erna was free to visit with her boyfriend, also a German Jewish émigré.

In April 1940 the girls learned that they could collect their U.S. visas. The generous Mrs. Jacobs helped finance their trip to Boston. As the ship docked in Boston Harbor, the girls realized how very far they had come from their sheltered and secure life in Freiburg. “We stood there on the boat, the three of us, no one to pick us up, no relatives, no strangers, no one, and we thought we really could jump overboard and no one would ever miss us,” said Toni.

The girls immediately boarded a bus for New York, where both their lifts of belongings and their aunt, Sophie, also a recent arrival, awaited them. Almost as soon as they reached new York, they received distressing news: the storage area in New York was full, and their lifts were being forwarded to another facility. The lifts were the girls’ only physical connection to the life they had been forced to flee. With no idea what awaited them, they decided to follow their lifts to a city about which they knew nothing and where they had no relatives or friends – Baltimore.

Continue to Part IV: Bringing Their Parents to Baltimore

All quotations and family history information are based on oral interviews with Toni Weil (JMM OH 0246, July 8, 1990), Julius Mandel (JMM OH 0268, June 23, 1991), Erna Weil, and Brenda Weil Mandel, and on materials in the Mandel collection (JMM L2002.102).