Everyday Heroes: Interview Part II

Article by Deborah Rudacille. Rudacille is a freelance writer and Dundalk native. Her book about her hometown Roots of Steel: Boom and Bust in an American Mill Town, was published by Pantheon in 2010. Article originally published in Generations 2009-2010: 50th Anniversary Double Issue: The Search for Social Justice.

Q: When you look back now, at how you chose to participate in this history, when so many didn’t, when you look at your younger self, what pushed you to say, I have to get involved?

I think it was my Jewishness. I grew up with those images [of the Holocaust] in my mind. And when I was in [Parchman] in my mind I related it to that. It was the same thing. There was the watchtower outside, you could see it through the high window in the cell, with guards and guns. I thought of people who had seen that same view in concentration camps. And people were being, for no reason at all, treated so badly.

Q: So you were making those links while you were incarcerated?

Absolutely. I felt that maybe if people had tried to do things . . . I can’t say, because you don’t know what other people were suffering, but I was gonna be there [weeping]. We all had relatives who died in the Holocaust. I didn’t know as much about it, my ancestry, till many years later, when material came out about the little shtetl where my grandparents came from. My grandparents migrated to this country, but the place where they came from, relatives we had left in those shtetls, were totally destroyed. But even before I knew that, I felt a oneness with the Jewish people.

Q: Do you think that this feeling explains why so many other Jewish people became involved, because they too saw and felt the parallels?

I can only speak from my personal experiences. The people in Glen Echo, the Greenbelt people, were almost all Jewish people. The same with the [white] people who marched on Washington in support of Brown vs. Board of Education. So many of the people at CORE who were white were also Jewish, a disproportionate number. The people I met in jail, the white women, a good number were Jewish. And people felt like similar to my experience, we felt that we had a similar situation to so many black people, and I think we were influenced by our own history of discrimination.

We felt one with black people, for unfortunate reasons. Terrible things had happened.

I want to tell you of a very difficult experience. When we were released from Parchman Penitentiary, the sheriff’s men came from Jackson to return us. Several men came with a little van and we were placed in the van. I remember Stokely Carmichael being in that van. He was released with me. But they did not take us initially back to Jackson. They took us way out in the country somewhere, far on some country roads. We all became very quiet and very frightened. Finally they stopped in the middle of nowhere where there was a house.

These guys were very rough, didn’t speak good English—I would say they were what we used to call bottom of the barrel. They walked into the house and were in there for a long time. Eventually, they came back out. I have no idea how long it was but it seemed like forever and with them came out a man who was totally unlike them. Blonde, tall, good-looking, well-spoken. And from a different class. And he was mainly talking to them and it felt like he was placating them. So they came back and we drove off. But we didn’t know what was going to happen to us. We thought it was the end. And later, people [Freedom Riders] were actually murdered. Schwerner, Goodman and Cheney.

Q: How many of you were in that van?

Six or seven.

Q: Women and men, black and white?

Yes. But when I discussed this with Joan Trumpauer (now Mulholland) [recently] she said she had the same experience and that other Freedom Riders might have too. I don’t know whether this was something they did just to frighten people or if something really could have happened.

Q: So it may have been just an attempt to scare you away. But it didn’t work.

No, because what happened was that from that Fill the Jails movement the voter registration drive developed. And a lot of people who had been in the Fill the Jails went back, like Joan.

Q: But you didn’t go back.

No. I was really—as were many of us—traumatized for so many years. But I feel blessed to have been in the period when something could be done. You could do something that really helped the situation.

Q: What about you, Larry. Do you feel the same way?

Larry: There is always a price to pay. I always thought that employment was the most important thing, so I was involved with CORE around employment issues. We’re talking about the early sixties. Kennedy was still in. We had a demonstration at Social Security led by Dick Gregory, who came down from New York. And I marched in it. And there was a price to pay for that. You’re no longer the bright guy who is a real talent.

Q: So your own career suffered?

Yes. I had been doing serious policy work, and then for about three years I was doing employee suggestions. They might as well have put me in a closet with a light bulb. And I was told as much by one of our assistant directors. He took me aside and said, “Larry if you do this, you are going to suffer.” Fortunately my wife Ann—and I spoke to her about it, because I was not going to be the only one affected, I had a wife and two small children—and she said, “Do what you think is right.” And so that’s what we did.

A lot of good came out of [that demonstration] in terms of the employment situation. Things began to open up. Then the next big campaign we started at CORE had to do with the commercial banks. You’d walk in and see all the employees were white. Maybe a rare black face. So we organized a group of CORE people, an integrated group wearing scruffy clothes, to walk into Maryland National Bank downtown—there were like twelve to fifteen of us, and we’d walk around and stare into the tellers’ faces and that got their attention. We met with some of the lower echelon bank officials, and they said “We do our best” [to hire blacks]. And we said, “That’s nonsense, you’re not doing outreach, if you were, you’d have more black employees.” So we did this with all the commercial banks. And we met with Bradford Jacobs, an editor for the Sun, and told him we were going to have a demonstration. Cardinal Sheehan got involved. He set up a meeting with us and the top echelon of the banks, and things got moving from there. It was a successful campaign because of Cardinal Sheehan’s intervention.

Q: You were still a full time employee at Social Security then? And had a wife and small children. You must’ve been a busy man!

Exactly. It’s so easy to burn out as a civil rights worker. It’s a burnout business. Your effectiveness if you are lucky is five years. And as a white man who got involved, you’re like a summer patriot. You can go in and get out whenever you wanted to.

Q: So you were involved for about five years?

At least. Until Black Power came in and whites were politely asked to leave.

Q: How many campaigns had you participated in by then?

Well, there was Social Security, then the commercial banks. And by then we had received publicity, so groups begin to contact us. We were contacted by some men who worked for the Department of Public Works in Baltimore City. Their situation was absolutely unbelievable. The dirtiest jobs were held by the blacks and all the supervisors were white. But that wasn’t the worst of it. The worst of it was there was a nice brick bathroom for whites only, so that when they get off work they could go in and wash up or do whatever they had to do. But the blacks couldn’t use that. The blacks had to use a portable outdoor chemical toilet without heat, running water, a sink, or electricity, twelve months a year! In the hottest and coldest weather. So I set up a meeting at the DPW, and we had black workers and the white big shots, and I was the one white guy with the black workers. At the meeting, one of the big shots kept calling the men “boys.” I let it go once, twice, and then I said, “Listen, these men are old enough to be my father, my uncle, my brother, they are not boys. They are men.” And all of a sudden it’s like opening up an emotional dam. The black men said “Yeah, yeah.” And of course that won the day. The important thing was that the city made changes.

I was so impressed by the caliber of these men. They weren’t stupid men. They were intelligent. And another thing you do in this business, I knew I could only do it for a short period of time, so you have to develop a grassroots leadership organization. And that’s what we did. And it’s easy to do because the men were so good.

Our objective in all these campaigns was to achieve a big payoff where there were a lot of jobs involved and something of lasting importance would result. And that was Bethlehem Steel (see sidebar).

Q: But then, after five years or so you were burned out…

Yes. And also when Black Power started, whites were invited to leave. I had very mixed feelings about it to be frank. I thought it was a lousy idea—the very antithesis of what I was fighting for and what CORE stood for—not looking for black power or white power or brown power. We were looking for an integrated society where all these threads come together. And that of course has not yet occurred. But there is a feeling of relief also, because this lets you off the hook. You don’t have to worry about your conscience any more prodding you and asking why aren’t you doing something.

But I had seen what the power of the law could do, in terms of the whole civil rights struggle. My daughter was in college at the time and my first wife said to me, “Larry, now is your last chance. Go to law school.” So with her support and urging I did go. I went to the University of Baltimore Law School at night and worked during the day at Social Security. This was about 1972 and I was forty-one or forty-two. So as a result of my experience with the civil rights movement, I became a lawyer. And I’m very glad I did. I was able to have a career in public law, first with the Social Security Administration and then with the Attorney General’s office.

Q: And you became a social worker, Helene?

Helene: That’s right. In 1972 when I was in the midst of a divorce, I moved to Baltimore to attend the University of Maryland School of Social Work. After I obtained a masters degree in clinical social work, I worked as a psychiatric social worker that specialized in geriatrics at the Baltimore County Department of Health. I did mainly assessments. It was service to try to avoid state mental hospitalizations of elderly people. I really enjoyed that work.

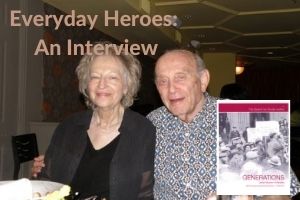

Q: When did you meet?

Larry: My first wife, Ann, died in 1977. Two years later, Helene and I met at the Westview Lounge in Catonsville. I was invited by a mutual friend, and Helene came with somebody else and I came with somebody else. And I had just finished arguing a case before the Maryland Court of Appeals, an adoption case which I won. But I hated social workers at the time because the social worker who handled this case – a sad case, custody of a child—I thought she didn’t treat my client fairly. So I did my usual smart-alecky thing and I told Helene, what did I tell you?

Helene: “I hate social workers!” He started an argument. But of course I knew he was interested in me right off.

Larry: And several weeks or a month or two later, I called her for a date and we got married a year later, in 1980.

Q: And was your shared history with CORE a bond?

Helene: Oh yes, definitely. That was an enormous thing.

Larry: Because you can talk about common experiences.

Q: And you are like soul mates.

Larry: Exactly.

Q: Is there anything you would like to say about your own involvement or the involvement of Jewish people in general on civil rights and where we stand today?

Larry: It’s a different world, thank God. I see my grandchildren, you don’t hear kids, or adults for that matter, talk like you used to hear in the forties, fifties, sixties. You see people of different colors and backgrounds getting together, without the handicap of the prejudice of race. This country has made such wonderful strides. It’s amazing to me. Who would have dreamt we’d have a black president?

Helene: Yes. That was incredible. And you can see that the children and grandchildren of the people who helped move this country forward have benefited. I have a personal wonderful experience of that. My nephew eventually married a young woman from Taiwan. He teaches at the University of Arkansas and his son goes to the Little Rock high school that was the battleground for implementing the Brown decision to integrate the schools. Well, my grand-nephew Joseph’s class published a book of essays about the desegregation of the school and Joseph called me up and interviewed me about my experience as a Freedom Rider. And his was one of the essays that was chosen to go in the book. But the fact is, if things hadn’t changed he would have been excluded because of the color of his skin. Because he is dark.

Q: So not only in the country as a whole, but in your own family you can see the fruits of your struggle.

Helene: Beautifully put. It made me so proud. By the way, Joseph is Jewish. His father is Jewish. His mother was not but converted. He has had his bar mitzvah.

Q: A Jewish Chinese kid living in Little Rock, Arkansas, and totally at home?

Helene: Yes. I don’t think he feels any different from anyone else. And with my granddaughter, I didn’t realize she knew anything about it. But I think it made her feel proud. You think they don’t notice what you’ve done, but then . . .

Larry: How many people in Julie’s class can say their grandmother is an ex-con?

The End