Intern Weekly Response: Museums and Neutrality 2019

Every week we’re asking our summer interns to share some thoughts and responses to various experiences and readings. This week we asked them to read a pair of articles by Gretchen Jennings on museum neutrality and find a third related article to explore and reflect on. To read more posts from JMM interns, past and present, click here.

Every week we’re asking our summer interns to share some thoughts and responses to various experiences and readings. This week we asked them to read a pair of articles by Gretchen Jennings on museum neutrality and find a third related article to explore and reflect on. To read more posts from JMM interns, past and present, click here.

The two articles presented were “The Idea of Museum Neutrality: Where Did it Come From?”and “Thoughts on Museum Neutrality: A Question of Balance.”

From Intern Hannah:

Desmond Tutu said, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.”

The issue of neutrality in museums is a complex one. We want to believe that when presented information, it is just information: unbiased, factual, and true for all. However, that has not historically been the case. Museums in this country have played the role of representing those with the most capital, and thus ability to make museums and memorials, meaning: land owning (i.e. formerly slave-owning) European men, which silences the voices of those oppressed by this group.

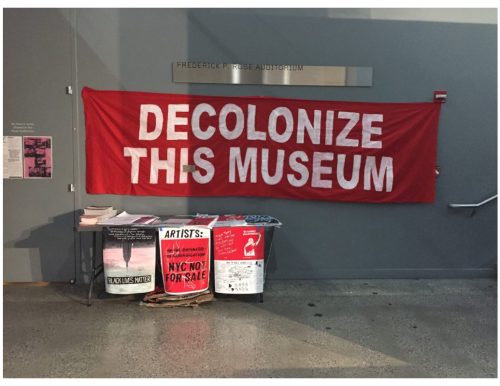

Nathan Sentance, in his article Your Neutral is Not Our Neutral, brings up the way that American natural history museums have historically presented Native American peoples as “primitive savages”, which lead to the oppression of this group, as it framed them as “inferior and in need of Western civilization.” This phenomena of bias being disguised as neutral fact is still an issue in our museums and memorials. Part of neutrality is understanding that we are not past these atrocities we are displaying, and we cannot talk about them in the past tense. Neutral is not the same at normative – museums should not be expected to follow societal fluctuations on certain events and topics, but truly discuss them as they happened and continue to happen. A sense of hope and closure is often the objective of museums, but that is not neutral, as most hard topics we are discussing do not have a clean end or triumphant victory. We do not live in a static world, and every event or phenomena has consequence in some way. We cannot be neutral in our remembrance, as that often means siding with oppressors by saying their story is just as important. The stories of oppressors are important to remember, only so we can make sure they are not recreated. There is a difference between lauding and presenting a mistake in history to learn from, and museums and memorials often mix up the two.

How do we know if we have bias? No human is truly neutral, as we all have our own implicit social ideas about right and wrong, and what certain objects or symbols mean. One person, or a small group of people from the same institution or background examining an object does not lead to a neutral examination. When telling a story, in a museum setting, or in any educational setting, it is necessary to tell whole stories, with whole truths. This means turning to marginalized groups who were affected by the objects and manuscripts presented in museums, as they are often stolen stories, or have the danger of being mistold.

As a person who is just starting my career in museums, this is a very important thing for me to keep in mind as I move forward. What is the most amazing about museums to me is their mass appeal. Museums are a very accessible way to learn new things. They are open for people to enjoy whenever they want for a small cost (or ideally, for free), people can explore expert made exhibitions on topics they perhaps didn’t know much about before through easily digestible captions and writings. In a country with extremely weak and frail public education, and an administration who does not seem to want to change this, museums are our best fainting chaise, smelling salt, and Gatorade. However, these museums do nothing for our community if they are teeming with bias. This bias is not very easy to see, especially if you don’t know to look for it. It is so easy to ignore or simply not see any bias in museums because of the way that exhibitions are set up to seem factual.

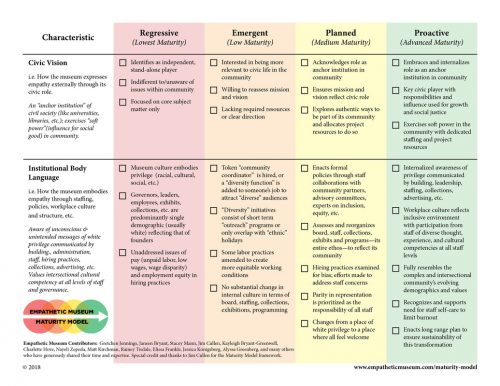

There are initiatives such as the Empathetic Museum Maturity Model which challenges museum professionals to turn to their own museum and check its biases, involvement in the local community, and the makeup of their staff. Part of white privilege is not realizing that you have white privilege, and the liberation from that is of the upmost importance when we, as museum professionals, are trying to tell full, complex, diverse stories. Museums are not a snapshot of the past that we can look at and throw away. They are a wealth of information on all the ways that history has gone both right and wrong, and it is our responsibility as museum professionals to strive towards exhibits and projects that show the true story, including all that happened, and how that affected the rest of the community, world, and the decedents of the people who were affected.

From Intern Ariella.

What exactly is museum neutrality? It’s a tough question to answer, in part because every museum interprets the concept of neutrality differently.

Gretchen Jennings and Dan Spock, in the articles above, agree that neutrality is difficult to enforce in museums. They agree that the goal behind staying neutral is unclear. Spock goes so far as to say that it can be damaging to the museum and its reputation.

The Brenham Heritage Museum has a different, more controversial take. According to a blog post titled “Museums Have Never Been Neutral, But They Should Be,” the author explains that museums were never invented with neutrality in mind. The earliest museums were collections of objects that their wealthy owners wanted to show off. And once museums took a more studious approach to their collections, they told whatever tale the institution wanted to tell. In Western culture, this typically gave respect only to the racial and cultural group that was overwhelmingly dominant. Today, as museums aim to correct their mistakes from the past, they are more open about expressing their more progressive views in exhibitions themselves, as well as through statements and social media.

Where the Brenham Heritage Museum differs, though, is in its analysis of neutrality in practice. The author feels that museums should always seek to tell the truth. Leaving out any piece of the truth, they say, is an act of cowardice. And this is a mistake made by museums that promote an agenda through their institutions.

At the same time, Brenham’s author feels that museums shouldn’t show support for “evil” ideas: “We will not give them a voice.” Brenham uses the KKK as an example of what types of ideologies are evil.

I agree with the Brenham author that museums should always present the full truth, while also ignoring viewpoints that are dangerous and unsubstantiated. But I don’t think that doing these things equals neutrality. Consider a science museum. It wouldn’t present a display about climate change and throw in the view of a climate change denier with equal weight as that of the scientist’s accepted studies. Nor should it do so in the name of presenting a fair view of the subject. A fair view can’t get in the way of presenting the truth.

Forced neutrality can even contribute to confusion for visitors. While on a visit to the Jerusalem Underground Prisoners’ Museum, the terminology used on labels, brochures, and explanatory materials kept changing. Sometimes the former prisoners were referred to as “terrorists,” sometimes as “militia fighters.” The attempt to hide what the museum thought about the topic got in the way of my experience: I didn’t know what the facts really said.

Instead, museums should try to present as many of the facts as possible, in as balanced a way as makes sense. The science museum should present climate change deniers as a viewpoint, but not as one that’s respected by most. Museums should focus on the facts, and if the facts are sometimes provocative, that’s even more reason that they should express them.

From Intern Elana:

One of the first things I realized in my museums studies courses was that museums are made by people. I had always known that museum staff, such as curators and designers, pick out objects and use text, placement, and design to interpret them, but it had never occurred to me that those people had motives, biases, and opinions behind those decisions. As Gretchen Jennings explains in her article, most people believe that museums should be neutral and have a duty to do so. However, this brings up the idea of what “neutral” in the museum context even means at all. Does “neutral” mean unbiased to most people? If this is true, then museums can never be neutral as there is always at least one person’s voice, typically many people’s voices, conveying a message through an exhibition or program.

Otherwise, does the public perceive “neutral” as a political term? This idea is brought up by Jennings in the article, “Thoughts on Museum Neutrality: A Question of Balance?” and was not one I had thought of before. Her idea of “balance” was intriguing to me, especially due to the contentious nature of that word in museums themselves. Jillian Steinhauer similarly engages with this idea in her article, “Museums have a duty to be political.” Both agree that museums are moving to a more inclusive place where they are presenting narratives that have previously been excluded from museums, especially due to their exclusive, privileged past, and are “balancing” the perspectives that are presented by museums. In this regard, “neutrality” or balance in political narratives is beneficial, but I do not see this as the way the public likely means “neutral.” Some even argue that presenting such underrepresented narratives is not neutral.

Whether the public concept of “neutrality” is unbiased or political, the issue does not wholly lie with museums themselves, but with the public perception of museums and its ideas about them. It is key to educate the public on the idea that museums are created by people with the goal of telling a story or making an argument based on fact, like non-fiction books or documentary films, and the people behind them have biases and motives just like any author. Creating an understanding of this concept in society would be beneficial to museums, so they could engage with more “non-neutral” narratives while the public would benefit from looking at exhibits more critically.

From Intern Mallory.

One of the best things about museums is being in an environment where facts are presented showing all sides of a topic, allowing for the viewer to form their own ideas and opinions on the matter. It was what always made me love museums, learning new information about topics I had never even heard about. This neutrality at museums, placing facts and information out for public viewing in an unbiased way is an idea what has been around for centuries.

The idea of neutrality is still associated with museums today, although it is becoming more challenging to truly remain neutral. Sean Kelley’s article, “Beyond Neutrality”, highlights the issue of neutrality in modern day society regarding the Eastern State Penitentiary. Kelley states that “I had concluded that our version of ‘neutrality’ was mostly taking the form of silence. As a coworker said at the time, ‘Oh, we talk about race and the US criminal justice system every day … our silence tells visitors exactly what we think about it’”.

This idea of silence voicing the opinions of the staff at museums can be seen across all museums. If only part of a topic is covered then that says something and can be interpreted as a bias on the subject. The design and placement of artifacts within an exhibit can have bias interpreted from it. While exhibits and programs can state facts, the silence that lingers between can show the unspoken opinions, ruining the neutrality of the environment. At Eastern State, they are removing the word “neutral” from their mission statement and programming, as remaining “neutral” would remove a side of the stories they present. They installed a piece which they call The Big Graph. This graph gives statistics about the US justice system and prisons in America, tracking changes over time. Eastern State wanted to show how the incarceration system in the US wasn’t working, specifically mass incarceration, and this graph was the way to show it. Feedback from visitors referred to this graph as neutral even though the staff had some doubts about being too blunt and straying from neutrality with the installation. While this can be seen an non-neutral, the staff and board of Eastern State all voicing their opinions through the Big Graph and the exhibit partnered with it, the feedback called it “neutral”, maybe because it told all the information, not just one side of the story.

The concept of neutrality in museums will continue to be tested, raising issues far into the future, “Neutrality is, after all, in the eye of the beholder” (Sean Kelley, “Beyond Neutrality”, 2016). It will always seem off, each person taking their own side in the matter. The absence of narratives from the past will always impact the neutrality of a museum, pieces missing from every story. And this will always lead to a critical eye claiming a museum isn’t neutral. Going forward, while neutrality should still be used to provide information in a welcoming and open environment for all, neutrality should not prohibit placing certain things within an exhibit. By doing so, the exhibit becomes non-neutral and blocks a voice of the narrative. Neutrality shouldn’t hinder the presentation within museums.

From Intern Megan:

After reading Gretchen Jennings’ two articles about museum neutrality, I read a third called, “Museums Are Not Neutral” by Lindsey Steward who is a museum educator and professional. All three articles left me to think about the word, “neutral” itself; while everyone can look up the meaning in the dictionary or online, does everyone agree as to what it truly means? Another question that really caught my eye from these articles was whether or not a code of neutrality in museums and subsequently, for example, not standing up for (or standing against) various social justice issues, can be considered a firm stance in and of itself. In short, is being neutral a decision to stay silent on issues or is it in fact an essential part of reporting facts and being accurate?

As a development intern at JMM, I feel like this issue is particularly interesting because I have the privilege to observe and contribute to the inner workings of a museum. Further, after visiting other museums as well, I can see that everyone in the museum world thinks differently and has their own rightful opinions, including myself. This relates to the question of neutrality because it helps to demonstrate how difficult it can be for groups of people and individuals to stay completely neutral. In addition, I believe this subject is so complex because, as mentioned, not everyone does in fact agree as to what being neutral means. If different people have different definitions, it makes it difficult to argue whether or not it is a correct stance to hold or if museums are already neutral or not. I think that the first step of tackling this topic is coming up with a recognized and established definition of neutrality as it relates to museums.

(I chose these images based on a couple past museum experiences I have had.)