Jewish Marylanders, Both Born and Made

Breaking Barriers in History

This post was written by JMM School Program Coordinator Paige Woodhouse. To read more posts from Paige, click here!

What is a barrier? Barriers can be physical – a material that blocks or inhibits movement. Barriers can be natural – such as oceans, rivers, or mountains. They can be immaterial – ideas, laws, or attitudes. The 2020 National History Day theme is “Breaking Barriers in History.”

National History Day, a non-profit that “creates opportunities for teachers and students to engage in historical research” (National History Day 2020 Themebook, pg. 4). This program begins in the Fall as students select their topic and begin researching. The program culminates with students presenting their work in original papers, exhibits, performances, websites, or documentaries and entering in local, regional, and potentially the national competition hosted at the University of Maryland at College Park.

This year, students in Baltimore and across the country will be researching individuals, communities, organizations, engineering and technologies, medicines, legislations, and more throughout history that have broken barriers.

JMM’s exhibits and collections tell stories of Jewish Maryland. This includes a variety of stories of individuals or communities breaking barriers. The Maryland Jewish community has produced many leaders who have made lasting contributions on a local, regional, national, and international scale. Issues range from labor relations and civil rights to helping the vulnerable to refugee resettlement to eliminating poverty, and much more. Below are three examples to get you started!

Henrietta Szold

Born in Baltimore in 1860 to Jewish immigrants Benjamin and Sophie Schaar Szold, Henrietta would spend her young adult life in Baltimore, teaching at her alma mater, Western Female High School. In the 1870s, Henrietta and her father would go to the Baltimore docks to greet new Jewish immigrants, mostly arriving from Eastern Europe and Russia. In 1889, Szold worked with the Isaac Baer Levinsohn Literary Society to form a night school for these immigrants to teach them English and American history.

In 1907, Henrietta joined the organization in which she would truly make her mark. Szold joined the Hadassah Study Circle, a Zionist women’s organization. Two years later, she traveled to Palestine with her mother. Horrified by the lack of medical supplies, Henrietta returned home determined to improve the conditions there. She founded the Hadassah organization to raise money to send nurses to Palestine. While serving as Hadassah’s president, she also became involved with the American Zionist Medical Unit, and later helped establish the Rothschild-Hadassah Hospital in Palestine and the Hadassah School of Nursing. Eight years later, Szold retired from Hadassah, but continued her work in Israel, serving as an elected official on the Yishuv’s National Council.

With the rise of Nazi power in Germany in 1933, she became the director of yet another organization, Youth Aliyah. She oversaw the resettlement and training of 11,000 refugee Jewish children for life in Palestine. On February 13th, 1945 Szold died at the age of eighty-five in the hospital that she helped build.

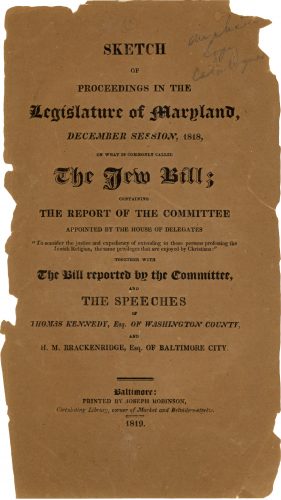

The Jew Bill

With the passage of An Act Concerning Religion, or the Toleration Act, in 1649, Maryland Jews and other non-Christians lost the ability to serve in municipal or state office, join the military, or practice law. However, there were very few Jews in Maryland at that time. Not until the late 1700s did Jewish families begin to appear in the growing port city of Baltimore.

When it was ratified in 1776, the Maryland State Constitution stated “No other test or qualification ought to be required on admission to any office of trust or profit than such oath of support and fidelity to the State … and a declaration of belief in Christian religion.” Even after the ratification of the Bill of Rights in 1791, the State of Maryland did not change its practices as the provisions of the First Amendment were considered to apply only to the Federal government.

In 1779, Solomon Etting, a prominent Jew in Baltimore, petitioned to have the state constitution amended to end discrimination of Jews. The Jews of Maryland did not sit idly by. They actively petitioned the legislature in 1824 for the bill’s passage. They wrote to editors in local and national newspapers, which began to run editorials in favor of the Jew Bill. Many people were offended to learn that such religious discrimination still existed in the government, nearly fifty years after the Constitution was established.

State delegate Thomas Kennedy, a representative from Hagerstown, took up the cause of Maryland’s Jewish community in 1818. When he started the fight, he had never met someone Jewish, but he believed fiercely in religious freedom. He introduced “An Act for the relief of the Jews of Maryland,” also known as “The Jew Bill.” With heavy opposition from the anti-immigrant wing of the Federalist Party, his bill failed year after year. Kennedy continued pressing for the Bill even at the risk of his political career. In 1823 he was defeated for re-election by Benjamin Galloway running on a “Christian Ticket.” Two years later he was reelected to office as an independent and helped secure enough votes for the passing of the Jew Bill in 1826.

Though the Jew Bill extended rights to Jews, other religious minorities would have to wait until 1867 for all religious requirements to be extinguished from the constitution.

Explore the JMM’s collection online for more primary and second sources about the Jew Bill here.

Experience a past program on the Jew Bill here.

Morris Schapiro & Boston Metals Company

For over 200 years, discarded metals, rags, paper, and animal hides have provided economic opportunities for immigrants and native-born Americans who collected, stored, brokered, and sold them – scrappers. The work was grueling, scrappers were stigmatized, and the industry was criticized as a source of social and environmental ills. Still, generations of individuals and families gravitated toward the work—including many Jewish scrappers. Our upcoming exhibit, Scrap Yard: Innovators of Recycling, shares stories of Jewish families who broke barriers – overcoming socio-economic barriers and stereotypes – while building one of America’s largest industries and innovating technologies and processes within it.

On such story is that of Morris Schapiro who immigrated to the U.S. at the age of 16, on the S.S. Pennsylvania. He traveled in steerage and was seasick nearly the entire journey, during which he was pickpocketed, which left him with 25 cents to his name when he landed. Though several of his cousins were already in the business in Baltimore, Schapiro struck out on his own Within a week, he had made over $100 – a fortune at the time and more than he had ever possessed. Schapiro immediately established the Boston Iron and Metal Company, collecting scrap metal from blacksmiths, machine shops, and chemical companies.

By the 1920s, Boston Metals Company had moved from a small warehouse in Fells Point to a large, waterfront yard breaking down Navy and civilian ships. In 1919 the S.S. Pennsylvania was seized by the U.S. Navy and renamed the USS Nansemond. It was put up for scrap in 1924. Schapiro identified the vessel as the very same one that brought him to United States on that dreadful journey. He bought and scrapped the ship at his Boston Metals Company in Baltimore. The fortune that Schapiro eventually built through scrap led him to other enterprises, including whiskey distilling, a “near beer” brewery during Prohibition, and the Laurel Park Racetrack in Laurel, MD.

Interested in more stories of the individuals, companies, and communities behind the scrap industry? Scrap Yard: Innovators of Recycling is on display October 27, 2019 to April 26, 2020. Bring your students to explore the stories of immigrant families who built the scrap industry in America.

JMM’s staff are huge supporters of National History Day and can often be found volunteering in Baltimore at school competitions and as judges at the City, State, and National Competitions. Let us take our support a step further. Our exhibits and educational programs can support your students as they practice critical inquiry and historical research – examining primary and secondary sources. We are delighted to provide complimentary admission and a complimentary bus for any Maryland Public School visiting the Museum.

Learn more about our education programs here.

Book a visit with your class today here.