Learning About Me, Museum-goer

A blog post by Deputy Director Tracie Guy-Decker. Read more posts from Tracie by clicking HERE.

Earlier this year, my family received the invitation to my first cousin’s October wedding in Snowmass, Colorado. When we discussed the possible trip, my husband and I decided to make a vacation out of it. Why fly all that way and only stay a few days? we asked ourselves. We extended the wedding weekend into an 8-day, Colorado vacation.

And what is a vacation without museums?

We visited several museums on our trip, and while I had fascinating experiences and left with very real memories, one of the most fascinating things about my museum visits on this trip was what I learned about myself as a museum-goer.

I enjoyed the Keota exhibition. I noted the use of the glass front cases with shelves all the way to the floor, and smiled as the museum educators replenished the eggs in the hen-house for kids to find. I read a few panels, and was interested by what I learned, but for the most part, I was not completely absorbed by any of the experiences.

We moved upstairs to additional exhibits. In their “Colorado Stories” core exhibit, History Colorado brings together a series of smaller exhibits that become vignettes to the visitor. Unlike the Keota exhibit, I found myself completely absorbed by some (Mountain Haven: Lincoln Hills, 1925-1965”) even as I breezed by others.

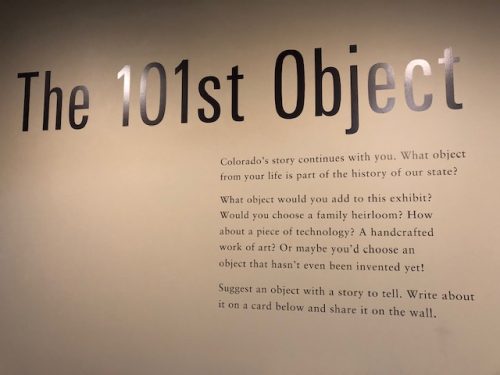

And then I got to Zoom In: The Centennial State in 100 Objects. This exhibit was a big white box, with 100 objects, labeled on platforms. Each label was numbered, and they were presented in order, roughly chronologically, from 1 to 100. There is no environment except the museum (though they do project landscape images on the back wall). There was no music, no interactives. It was not an immersive experience like the one downstairs, no props to create the environment, like the ones I’ve written about before.

As a museum-goer, that presentation grabbed me, and wouldn’t let me go. I needed to read every label, in order. The curators worked hard to make their 100 objects representative, so there were Native American artifacts juxtaposed against white settlers’ material culture which were adjacent to the personal effects of members of the Chinese-American community who came to Colorado en masse to work on the railroad. There were objects representative of everyday lives and others that carried the weight of historical significance. I found the juxtaposition arresting and fascinating.

I read every word in that gallery.

Somewhere in the 40s, there were visitors ahead of me who were not on pace with my reading. I got annoyed that they were in my way and I had to read out of order.

After I left the Zoom In exhibit (long after my family had moved on), we came upon Denver A to Z. It was a fun exhibit where I learned a bit more about the city I was visiting, but I found it’s layout disorienting. It wasn’t in alphabetical order, and that left me feeling like I was out of sorts.

Visiting the Keota exhibit, Zoom In, and Denver A to Z in the same trip, a pattern in my museum-going preferences became plain. In an immersive experience, I let the environment wash over me. I didn’t feel the need to read every text or interact with every artifact. I passed through the environment and waited for stories to grab me. In an exhibit like Zoom In, on the other hand, where the environment is nothing other than a gallery, I felt the need to understand every artifact, to absorb every label. I sought out the stories behind every one of those 100 objects.

The contrast is an interesting insight into the kind of museum-goer I am. What kind of museum-goer are you? Do you know? What presentation of story is more compelling to you? What kind is easier for you to learn? Maybe you’ll pay a bit more attention next time you visit a new exhibit to how you react to the environment, the label copy, and the artifacts. All of these questions come into play as curators, registrars, exhibit designers and other staff work to put together exhibits. I’m having a great time watching the interface between what museums create and how visitors interact with that creation—both at JMM and at museums I visit around the region and the country.