Lost in Transliteration

A blog post by Executive Director Marvin Pinkert.

A blog post by Executive Director Marvin Pinkert.

I think I’ve finally adjusted to Hanukkah. I don’t mean “Hanukkah”, the holiday I’ve celebrated for 60 years, I mean “Hanukkah” the spelling that has become popular in my lifetime.

Taking the holiday decorations out of the closet is my annual reminder that transliteration can transform tradition. I grew up with a beautiful blue banner that proudly proclaimed “Happy Chanukah” right above our menorah (a metal candle holder of very simple design that made up in weight what it lacked in elegance). I never for a moment questioned the perfection of this spelling.

But in the 1980s, – when our kids were young and our old banner disheveled from years of Scotch tape being applied and removed – I had to purchase a new banner and discovered that a lot of options had been added to the transliteration list. I settled on a multi-colored model with fringe and the phrase “Happy Hanuka”. It appeared that this peculiar spelling was an aesthetic choice, as the nearly even number of letters allowed the Star of David that separated the words to be placed exactly in the middle.

For many years I continued to look for “Chanukah” cards (just one of my atavistic preferences – like my nostalgia for the German beer hall melody for “Adon Olam”).

Of course, Hanukkah and its problematic initial letter are not unique. I understand that before we renovated the Lloyd Street Synagogue there was a lively discussion about “mikveh” vs. “mikvah”. As a former volunteer for Congressman Abner Mikva, I confess that I would probably have come out on the losing side of this debate.

Hebrew transliteration is actually relatively straightforward compared to my experience in East Asian Studies. I still cringe when I hear commercials for Toyota Camry (to rhyme with “lamb tree”). The Japanese word is “kanmuri”, meaning “crown”, and there is no “‘a’-as-in-‘can'” sound in Japanese – the sound is “a” as in “Genghis Khan”.

Speaking of Genghis Khan, when I started studying history his birth name was Temujin. But in many articles written today you will find that he was born Tiemuzhen. This reflects one of the most dramatic changes in transliteration in the 20th century. Until the thawing of relations with mainland China, most Western scholars used the Wade Giles system to romanize Chinese words (named for the British diplomats who developed and refined the system). The dominant system today is the “pinyin” system, the official transliteration practice of the People’s Republic of China.

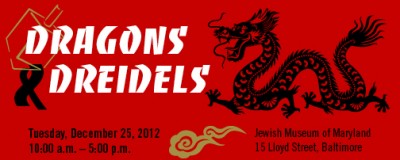

In “pinyin”, Mao Tse Tung became Mao Zedong and Mah Jongg became Ma Jiang. No matter how you spell it, it’s still fun to play (I mean “Mah Jongg” not “Mao Tse Tung”). So I hope you’ll join us on December 25 when we all have “phun” at the Dragons and Dreidels program – no transliteration required.