On the Corner: Growing up Jewish in a Gentile Neighborhood

By Deborah Rudacille. Ms. Rudacille is Visiting Professor of the Practice at UMBC and the author of ROOTS OF STEEL: Boom & Bust in an American Mill Town, a workers history of the Sparrows Point steelworks in Baltimore County.

Hampden, Waverly, and even (G-d forbid) Pigtown—these were not Jewish neighborhoods. Yet in the first half of the twentieth century they and other working-class Baltimore neighborhoods were home to numerous Jewish families who lived mostly “on the corner,” above or beside their groceries, confectionery stores, and other shops. The experiences of Jewish children, now senior citizens, who grew up in those gentile neighborhoods reveal an alternate history lived parallel to the more familiar narrative of ghettoization. Their stories summon up a vanished era before the city’s Jewish population migrated nearly en masse to the northwest suburbs—and offer a glimpse of what might have been had Baltimore’s Jewish residents instead dispersed in the manner of other ethnic groups seeking assimilation.

“We were the only Jewish family in our neighborhood,” says Rhea Feikin, who grew up in Hampden in the 1940s. Her father’s eponymous store, Ben’s, was located at 1506 W. 36th Street and she attended Hampden’s Robert S. Poole Elementary where she was the only Jewish student in the school. “It was not unpleasant,” she says today. “I did feel like an outsider but I learned how to be a good outsider, how to get along and fit in without losing my own identity.”

Though many believe that the formation of a strong Jewish identity hinges on growing up surrounded by other Jewish people, Feikin’s perspective is echoed by other Jewish children raised on the corners. “For many years, my best friends were non-Jews because we lived very far from a Jewish area,” says Morty Weiner, who lived on Polk Street near Clifton Park in northeast Baltimore from 1924 till 1943. At the same time, “I never questioned that I was Jewish.”

Other than his immediate family, there were no other Jewish people in the community where his father operated first a confectionery store and then a grocery. However, Weiner’s parents maintained close ties with a large extended family spread throughout the city. “On weekends and whenever the store was closed we would visit relatives, my grandmother, aunts, uncles, and they would come to us,” he says. Many of those relatives also operated groceries in gentile neighborhoods, he recalls. “My father and his relatives called themselves Weiner Bros and they had five stores between them. My grandmother and her daughters also ran grocery stores in non-Jewish neighborhoods.”

The presence of Jewish families in working-class gentile neighborhoods was motivated by purely economic factors, say those who grew up on the corners in the pre and immediate post-war eras. “The only reason Jews lived in a non-Jewish area was economic, to have a business there,” says Bernie Raynor, whose father operated first a confectionery store, then a grocery, and then a package goods store on Barclay Street in Waverly. Raynor’s father operated a business at that address from 1938 until his death in 1959, though Raynor himself left the neighborhood in 1949.

Like other corner merchants, his parents were first generation Americans who had immigrated to the U.S. with their own parents as young children. “My parents came here at age two or three and they spoke English. We never spoke Yiddish at home,” says Raynor. Until he was about seven years old, the family lived on Chester Street in East Baltimore. “We lived in a tenement,” he says, “multi-story, multi-family.” Even there, however, he had a mixed group of neighbors. “The people who lived downstairs were Polish Catholics. I picked up a lot of Polish words from them.”

His family moved to Pimlico—completely Jewish at that time—for a year, but when his father lost a job as a newspaper carrier in 1937, economic stress led to them to Waverly. “One way of making a living back then was the mom and pop store,” he explains. “There were no supermarkets and every corner had its dry goods store or confectionery, tailor or grocery.” Running a grocery in those days was hard work, he recalls. “We were open from six a.m. to midnight and we all worked in the store.”

A strong sense of Jewish identity without a strict adherence to Jewish practice is a common thread running through the reminiscences of Baltimore Jews raised on the corners. That may be due to the long hours worked by their parents, as well as the fact that most did not have a neighborhood synagogue. Morty Weiner says that though his parents did not regularly attend shul, they kept a kosher home and attended services on the High Holy Days. That seems to have been a common pattern. “We were not very observant though my mother and father kept kosher,” says Rhea Feikin. “I would run around the neighborhood eating bacon but my parents didn’t care.”

Bernie Raynor’s parents similarly observed the spirit, if not always the letter, of dietary laws. “My mother and father had certain things where they would turn their heads,” as when on Saturday afternoons when his mother would take him and his sisters downtown to the Hippodrome to see a show and afterwards for Chinese food. “That was not kosher,” he laughs.

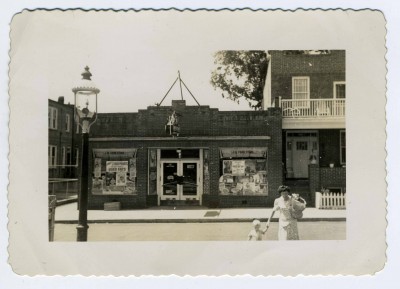

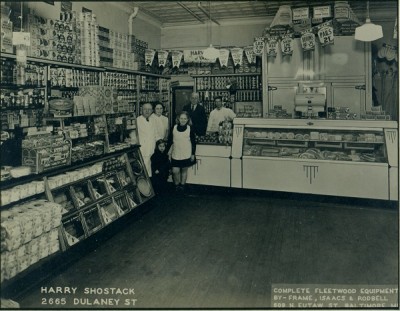

Debby Shostack Friedman’s parents—who owned a grocery store on Dulaney Street in Southwest Baltimore near Pigtown in the 1940s—kept kosher “though they would always complain about how expensive it was to get kosher meat,” she recalls. “They would say that they were going to stop but they never did.” Her family traveled to Lombard Street to stock up on kosher perishables, as did Raynor’s family. Like others profiled here, the Shostacks’ store “was closed only two days a year,” Friedman says. “On the first day of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. We would pack a suitcase and go to my grandmother’s house,” on Cottage Avenue in Park Heights.

Author Gilbert Sandler points out that unlike Jewish shopowners who lived in rural areas where they were often the only Jews for hundreds of miles around, “if you lived in the city you were a streetcar away from other Jewish people.” Jewish children living in gentile neighborhoods attended the Beth Tfiloh youth program and Jewish summer camps, visited family members in Northwest Baltimore and were drawn like moths to the historic epicenter of Jewish Baltimore to shop and to kibbitz. “They flocked to Lombard Street from all points of the compass,” says Sandler, “like it was a watering hole in the jungle—not for the pickles but to say this is who we are, to identify themselves as Jews.”

Unlike other predominantly gentile neighborhoods, Waverly, where Bernie Raynor lived, had a neighborhood synagogue. Ahavath Israel at 2342 Barclay Street operated a Hebrew school that drew boys from North Avenue, 33rd and Greenmount Avenue—where there were many Jewish shopowners—up to Towson. “We went every day but Friday—just boys, no girls,” says Raynor. “It cost fifty cents a week.”

Approximately forty boys from kindergarten through bar mitzvah age attended the school, he says, with the teacher working with two or three at a time and the others playing ping pong or step ball until called to work. Even so, “we had to go out of our way to find Jewish boys or girls to be friendly with,” he points out. “Just because you attended Hebrew school with a group of boys didn’t mean you would be friends with them.”

As children of busy shopkeepers, the corner kids were generally left to their own devices when they weren’t working themselves. “We were much more independent than kids today,” says Raynor. “At eight, nine years old, I went on the streetcar by myself.” Friedman recalls a similarly liberated childhood, running the streets of Southwest Baltimore with the neighborhood children. “I was outside with those kids all day long,” she says. “Even at seventeen,” when her parents closed the store and moved to a Jewish neighborhood, “I could have stayed.”

Her elder sister, Harriet Pollack, has more mixed memories of the community, where the smell of animals being butchered in nearby stockyards in summer would send the family fleeing to their car in search of fresh air. “They were not my kind of people,” Pollack says of her former neighbors. “I knew I wasn’t one of them.” The difference in the two sisters’ attitude may be due to the fact that Harriet, six years older than Debby, remembered living among other Jewish people, whereas her sister knew only Pigtown. Born on Lawrence Street in West Baltimore, where her parents operated a shoe store, Pollack says “I must’ve been six or seven when we moved because I went to kindergarten and first grade in that area. There was a street of Jewish shopowners, who all lived with their stores and were all friendly with each other. We lived between the chicken and egg store and the butcher.”

After the move to Dulaney Street, her contact with other Jewish people was limited, even though “about six blocks away down Wilkens Ave was a Jewish area,” she recalls. “I never really got friendly with the children there because they went to a different school.” Instead, she spent every weekend at her grandmother’s house on Cottage Avenue in Park Heights. “It was a long street with many girls my age,” she recalls, “and I had lots of friends there.”

Meanwhile, her sister Debby—a self-described “tomboy”—chose to remain in Southwest Baltimore on weekends. Though she attended Hebrew school and went to Jewish day camp for a couple of summers, her closest friendships were with the children who lived on the blocks near her parent’s store. “It was a rough neighborhood,” Friedman admits, but she was “more aggressive with the other kids” than her older sister, and so felt more comfortable taking part in their games and activities. “The children I played with were wonderful,” she says, even though “I wasn’t allowed to go into a couple of the homes because they were drinking houses.”

Like other Jewish children growing up among gentiles, the Shostack girls became junior cultural anthropologists at a young age—intrigued by the strange habits and lifestyles of their neighbors. “I’ll never forget the first time I saw crepe on a door when someone had passed away,” Pollack says. “In those days they laid people out at home. That was different. I never went in though, because I was scared to death.”

Then too, her bedroom window overlooked a bar and she was amazed to see the working men of the neighborhood “lining up for a pitcher of beer at 6 a.m. It was breakfast food for them.” Those men may have been queuing up for a drink after working the night shift, not drinking their breakfast, but that would have been a distinction lost on a child whose father was not a factory worker.

Bernie Raynor, who delivered beer for his father in Waverly, was similarly struck by the gregarious, alcohol-fueled socializing of his community. “They would call us at two in the afternoon and you’d go over with the beer and they’d be playing cards, smoking and drinking,” he recalls. Obviously, not all the neighbors fit this working-class stereotype but the fact that even today the Shostack sisters and Raynor recall without prompting memories of daytime drinking in their old neighborhoods indicates how odd this behavior must have seemed to them as children.

~END OF PART ONE~