Second Cousins, Card Parties, and Chickens in the Back Yard Part III

Article written by Deborah R. Weiner, former JMM research historian and family history coordinator. Originally published in Generations – Winter 2002: Jewish Family History. Information on how to purchase your own copy here. Many thanks to JMM collections manager Joanna Church for re-typing this article.

Article written by Deborah R. Weiner, former JMM research historian and family history coordinator. Originally published in Generations – Winter 2002: Jewish Family History. Information on how to purchase your own copy here. Many thanks to JMM collections manager Joanna Church for re-typing this article.

Part III: Social Visiting

Miss the beginning? Start here.

Through the years, economic imperatives and kinship ties combined with pressing communal needs to ensure that community and family life remained deeply intertwined. Not all extended families were close; geographic distance, the pressures of assimilation, the all-consuming drive for economic success, and family feuds were some of the forces that could cause small-town Jews to become isolated from one another. But a strong desire to maintain Jewish practice, identity, and community encouraged them to rely on each other in ways that gave a particular cast to Jewish family life, as immediate and extended families responded to the challenge of being Jewish in a very non-Jewish environment.

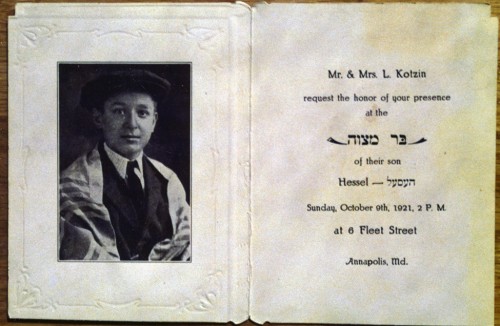

Lacking synagogues in the first half of the century, Jews on the Eastern Shore and in St. Mary’s County held communal activities in their homes, from gathering a minyan for services to holding weddings and bar mitzvahs. Life cycle events combined a homey, family-based feeling with the solemnity required to mark a community milestone. The 1913 St. Mary’s County wedding of Max Weiner and Sadie Schochet was held at the home of the bride’s cousins, Max and Lena Millison. Local Jewish families joined with gentile friends as well as a rabbi and relatives imported from Baltimore to witness a ceremony that “began in the parlor and was concluded under a canopy erected for the occasion under the porch,” reported a local newspaper. After the “strictly” Orthodox ceremony, “an elaborate and handsomely prepared supper … was served in true Hebrew fashion, which was enjoyed immensely by the 100 or more guests.” The preparations leading up to such home-centered extravaganza can only be imagined. Recalling his mid-1910s “five-day bar mitzvah” at his family’s home in Havre de Grace, Sidney Schreter marveled that “my mother did all the cooking. She must have cooked for weeks before!”[1]

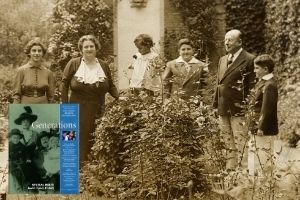

Historian Eric Goldstein notes that an “elaborate pattern of ‘social visiting’” among interrelated small-town Jews constituted “perhaps [their] single most important social activity,” allowing them to “escape, at least temporarily, from the rigors of living in isolation from Jewish society.” More formal communal events such as weddings and bar mitzvahs also took on a symbolic significance beyond their usual meaning. Goldstein suggests that small-town Jews “used elaborate wedding celebrations to underscore their ability to nurture Jewish family and social life.” Such major events demonstrated that “the community could stage a full-blown Jewish celebration, that it need not send its members to Baltimore to get married, and that Jewish continuity was possible in a small-town context.”[2]

Many of Maryland’s small-town Jewish congregations eventually built synagogues that became the focal point of communal activity. In 1920s and 1930s Cumberland, Elaine Jandorf recalled, “it was the center of their life, that little synagogue. And everybody was related, they were all friends, they played cards together …” For Miller and Heilig descendants on the lower Shore, major life cycle events occurred several times a year when Barry Spinak was a youngster. “It was a big family and we all went to everything,” he commented.[3]

Continue to Part IV: A Do-It-Yourself Attitude

[1] St. Mary’s Enterprise, 29 November 1913; Sidney Schreter, interview with Gertrude Nitzberg, Baltimore, 18 March 1977 (JMM OH 0051).

[2] Eric L. Goldstein, “Beyond Lombard Street: Jewish Life in Maryland’s Small Towns,” in We Call This Place Home (Baltimore: Jewish Museum of Maryland, 2002), 41, 48.

[3] Elaine Jandorf, interview with Jacqueline Donowitz, Baltimore, 15 November 2000 (OH 0392); Spinak 2001 interview.

1 reply on “Second Cousins, Card Parties, and Chickens in the Back Yard Part III”

I want to change to Jew and start attending the Synagogue from now on.

Shalom.