The American Delegate(s)* Part II

Written by Avi Y. Decter. Originally published in Generations 2007-2008: Maryland and Israel

Part II: The Congress Participants

Miss the beginning? Start here.

The first World Zionist Congress convened in Basel, Switzerland, on August 29, 1897. For three days the Congress participants listened to speeches and reports on the condition of world Jewry, debated issues, adopted a program “to establish a home for the Jewish people in Palestine,” and defined the fundamental structure of a new World Zionist Organization.[1]

During the course of the Congress, an official list of participants was published, naming 199 men and women. Two-thirds of these “participants” were there in their “private capacities,” mostly individuals with a strong interest in Zionism and the nationalist ideal. Sixty-nine of the participants were designated by asterisks (*) as “delegates” representing Zionist organizations or Jewish communities. (As in baseball, asterisks do matter.) Also on the official list were about a dozen journalists and several guests.[2]

Most of the participants came from Europe, as might be expected given its dense concentration of Jewish population at the time and the expectation Zionism would alleviate the burden of antisemitism, especially in Europe. Only four people were cited in the official Congress list of participants as coming from America. Davis Treitsch (1870 – 1935), listed as a participant from New York City, appears to have been a German national who resided in New York for several years while studying immigration issues. Treitsch, an advocate for Jewish settlement in Cyprus, the “gateway to greater Palestine,” paid his own way to Basel to lobby for his pet scheme.[3]

A second American participant was the redoubtable Rosa Sonneschein (1847 – 1932), editor of The American Jewess, who was present as a journalist. Sonneschein, who had advocated for a Jewish homeland in Palestine in the pages of her journal, came to Europe to cover two conferences: the Zionist Congress in Basel and, in October, the Woman’s Congress in Brussels.[4]

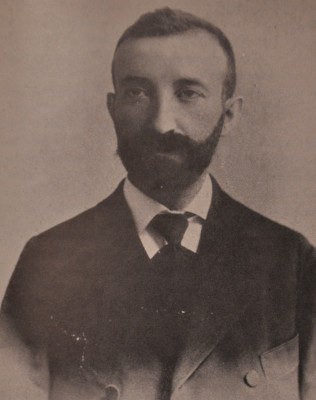

The other two Americans at the Congress were Rabbi Schaffer of Baltimore and Adam Rosenberg (1858 – 1928) of New York City, both of whom were marked as official delegates in the participant list of the Congress.[5] Adam Rosenberg’s journey to the Congress was complicated. Born in Baltimore, the son of an immigrant German rabbi, Rosenberg grew up in Germany, returned to the United States around 1886 as a young man, and became an attorney in New York. Although he is little remembered today, Rosenberg was among the leading American Zionists of his generation. In addition to being active in New York’s Hovevei Zion, in 1891 Rosenberg founded and presided over Shavei Zion [Returners to Zion], an organization composed of investors who sought to buy shares of land in Palestine for Jewish settlement, and, if all went well, to promote agriculture in the new Jewish colonies.[6]

On behalf of Shavei Zion, Adam Rosenberg traveled to Europe and Palestine in 1891. While in Europe he met with key Zionist leaders who had decided in September of that year to establish an “International Committee.” In January 1894, on a subsequent trip to Europe, Rosenberg participated in the first “World Congress of Hovevei Zion,” at which he proposed establishing a “Central Zion Federation” to offset the fragmentation and duplication of effort he had found among the Zionist organizations and to serve as the single coordinating body for world Zionism.[7] In the following years Rosenberg continued to agitate for a Central Committee of Hovevei Zion in the United States and also for a world center. In this regard Rosenberg was a forerunner of Theodor Herzl, and when Herzl succeeded in establishing the Zionist Congress and a World Zionist Organization, Rosenberg’s leadership role quickly eroded.[8]

When Herzl began organizing the first Zionist Congress, Adam Rosenberg was among the leading figures in American Zionist circles – and one of the few Zionist leaders who had direct experience of conditions in Palestine. On Rosenberg’s initial visit to Palestine in 1892, he struggled to secure title to land in the Golan and to initiate Jewish settlement and agricultural development. He returned to Palestine in late summer of 1895 and spent two years there trying to promote settlement in the Golan.[9] By the summer of 1897 Rosenberg was exhausted, sick, and ready to return to America. That spring, however, he received a personal invitation from Herzl (via Wilhelm Gross) to attend the Zionist Congress. Herzl – mistakenly – thought that Rosenberg was the “Director of the Hovevei Zion in America,” and this, when Rosenberg, leaving Palestine, decided to attend the Congress in Basel, he, together with Rabbi Schaffer, was listed as a delegate.[10]

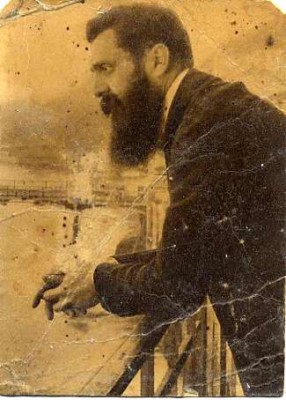

Rabbi Schaffer, on the other hand, was actually chosen by a Zionist organization as its official delegate. Abba Shabtei ben Chaim Aaron Schaffer was born in Latvia, the son of a rabbi. After attending various yeshivot he moved to Berlin, where he studied at Rabbi Azriel Hildesheimer’s Rabbinical Seminary and also the University of Berlin. In 1889 he completed a Ph.D. at the University of Leipzig, and the next year was granted rabbinical ordination. In 1893 Rabbi Schaffer came to the United States to take up the pulpit of Congregation Shearith Israel in Baltimore, where he served as rabbi until 1928.[11]

Within two years of his arrival in Baltimore, Rabbi Schaffer was elected president of the Baltimore Zion Association (1895) and, two years later, was sent to Basel as the Association’s representative. Rabbi Schaffer was not, however, the only candidate for this role. Wolf (Zev) Schur (1884 – 1910), editor and publisher of the Hebrew-language paper Ha-Pisgah, lobbied his friends in Baltimore to be named as a delegate, claiming that he would attend the Congress with a smaller travel subsidy. Schur’s efforts were unavailing and Rabbi Schaffer embarked for the Zionist Congress (followed by an extended trip to visit family and friends).[12]

So, in August 1897, Schaffer, Rosenberg, Treitsch, and Sonneschein arrived at the Zionist Congress in Basel. Rabbi Schaffer was the delegate of a Zionist organization; Rosenberg was also an official “delegate,” through Dr. Herzl’s misunderstanding; Treitsch came as a private individual; and Sonneschein was there to report on the Congress. Surviving records do not indicate whether Schaffer, Treitsch, or Sonneschein spoke during any of the plenary sessions. Adam Rosenberg, in contrast, spoke twice, reporting to the Congress on conditions in Palestine and on the state of American Jewry – though Rosa Sonneschein tartly declared that the altter speech represented “simply his own views. It is to be hoped that the Congress will not accept the impression of an individual as an official report.”[13]

In the event, both men and women participated in the Congress proceedings (though the ladies were denied the vote), and all of the make participants – regardless of their private or official status – were put on an equal footing.[14] So, in these circumstances, did it matter at all if one was a “delegate” and another simply a “participant,” or was this a distinction without a difference? To Herzl in particular and to the other Congress organizers as well, the distinction did matter. To understand why we must touch on their intentions and the meaning they attached to the first Zionist Congress.

Continue to Part III: A National Assembly

Notes:

[1] S.U. Nahon, ed., The Jubilee of the First Zionist Congress, 1897 – 1947 (Jerusalem: World Zionist Organization, 1947), 54.

[2] Haiyim Orlan, “The Participants in the First Zionist Congress, “ in Herzl Year Book VI (New York: Herzl Press, 1964-65), 133-152.

[3] Oskar K. Rabinowicz, “Treitsch, Davis,” in Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd ed. (Detroit: Thompson Gale, 2007), Vol. 10, 146. See also Oskar K. Rabinowicz, “Davis Treitsch’s Colonization Scheme in Cyprus,: in Herzl Year Book IV (New York: Herzl Press, 1961-62), 119 – 206. See also Feinstein, American Zionism, 104.

[4] Rosa Sonneschein, “Something about the Woman’s Congress in Brussels,” American Jewess, Vol. VI, no. 1 (October 1897).

[5] Praesence-Liste.

[6] Israel Klausner, “Adam Rosenberg,” in Herzl Year Book 1 (New York: Herzl Press, 1958), 323ff. and 277f.; Israel Klausner, “Rosenberg, Adam,” in Encyclopedia of Zionism and Israel (New YorkMcGraw-Hill, 1971), Vol. 2, 963.

[7] Klausner, “Adam Rosenberg,” 259-263. Also, Feinstein, American Zionism, 52f.

[8] Klausner, “Adam Rosenberg,” 277ff.

[9] Klausner, “Adam Rosenberg,” 267-237.

[10] Klausner, “Adam Rosenberg,” 274

[11] Arnold Blumberg, A History of Congregation Shearith Israel of Baltimore (Towson, MD: Towson State University, 1970), 4. Rabbi Schaffer continued as Rabbi Emeritus until his death in 1933.

[12] Jacob Kabakoff, “The Role of Wolf Schur as Hebraist and Zionist,” in Essays in American-Jewish History (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1958), 439 and 443f.

[13] Rosa Sonneschein, “The Zionist Congress,” in American Jewess, Vol. V, No. 7 (October 1897): 15.

[14] Orlan, Participants in the First Zionist Congress,” 135, note 8. Compare Rosa Sonneschein, “The Zionist Congress,” 20: “And strange to say, with this strong craving for liberty and equality, the Zionists began their proceedings by disfranchising women.”