A Single Suitcase

A blog post by Director of Collections and Exhibits Joanna Church. To read more posts by Joanna click HERE.

Last December, we reprinted an article from our journal, Generations (Winter 2002), telling the story of the Weil family and their arduous journey out of Germany in the early days of World War II. I’d like to add an illustration to that story, in the form of a plain leather suitcase:

In 1938, Theo and Hilde Weil lived in Freiburg, Germany. Their three young-adult daughters, Toni, Lisa, and Erna, had a clear sense of what was happening to Jews in their country, and urged their parents to begin the lengthy and expensive process of applying for travel papers to the United States. Kristallnacht – and the subsequent arrest and detainment of Theo, which left him bedridden for several weeks after his family rescued him – showed the senior Weils that it was indeed time to leave their home and try to start over in a new country. In addition to moving forward with their visa applications, the family packed up much of their furniture and belongings and shipped them ahead to New York, hoping they’d soon be able to go there themselves.

“The trouble in Germany was things didn’t happen suddenly. It was a little and a little and a little, and you can always take a little more.” – Toni Weil Mandel (JMM OH 246)

Shortly afterward, the three Weil sisters left Germany on their own, working and saving money for some time in England before they secured their US visas. After arriving in Boston in 1940, they learned that the crates of family furniture were being moved from New York to Baltimore; not knowing what else to do, the girls moved here as well, and managed to find work and shelter.

In the meantime, however, their parents in Freiburg were not faring well. Despite finally receiving clearance to come to the US, the Weils were not permitted to leave Germany. In October of 1940, the Nazis announced that all remaining Jews in Freiburg would be deported, with only an hour’s notice. The Weils were allowed one suitcase in which to pack their things.

While they were packing, Hilde wrote a quick letter to her daughters, which she later managed to shove out of the sealed train. The letter was found and mailed, by an unknown person, to the Weil sisters in Baltimore, who otherwise would have had little or no idea what had happened to their parents.

Hilde and Theo Weil, Hilde’s mother Lina Wachenheimer, several other relatives, and their Jewish neighbors were taken to France and imprisoned in Gurs. Once the girls discovered what had happened, they began working to secure the release of their parents and grandmother, gathering the money, affidavits, and travel papers necessary to prove that these people – forced to leave their home without identification – were the people they claimed to be, and were, thanks to their earlier visas, permitted to come to the US. Eventually their efforts succeeded, and in April 1941, the senior Weils arrived in Baltimore … still carrying their single suitcase. (Lina stayed in New York, with her daughter Sophie.) It is important to note that most internees at Gurs were not so fortunate.

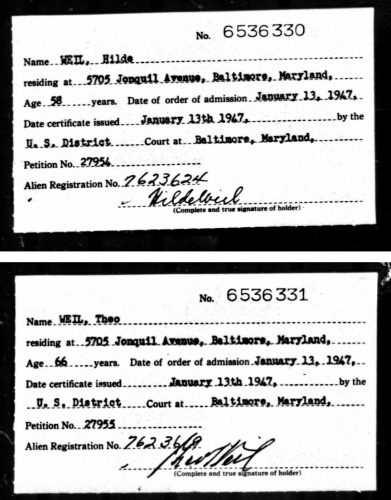

Theo and Hilde settled in Baltimore with their daughters but, weakened and depressed by their time in the internment camp, their lives were never the same. In an interview, Toni later remembered that her mother was “starved to death” when she got to Baltimore, and that the first shocks of America’s abundance were hard for Hilde to bear: “When we took her the first time to a food market, she asked us to take her out, she couldn’t see that food. She said, what she’d seen in a few seconds would feed that camp for years.” (Toni Weil Mandel, JMM OH 246) Thankfully, the Weils had a community of people who had endured similar experiences; they joined Chevra Ahavas Chesed, a charitable organization and burial society founded by European Jewish refugees in 1940. They were both naturalized as US citizens in 1947 and lived in Baltimore for the rest of their lives; Hilde died in 1961, at the age of 73, and Theo died in 1970.

Take some time today to put yourself in the shoes of Hilde and Theo Weil in October 1938. Though reluctant to give up their home and lives in Freiburg, they had shipped most of their large belongings off to a country to which they had no assurances they would be able to move. Their lives were in danger. Their daughters were on their own, across an ocean. They were given an hour to pack the remainder of their belongings into a single suitcase, knowing they were about to be sent off to face an uncertain fate. If this happened to you, how would you react? What would you pack? How would you get word to your children? These are questions that we at the JMM take seriously, as part of our educational mission, and I urge our readers to consider them seriously as well.

1 reply on “A Single Suitcase”

Nicely done, Joanna! My father’s oldest sister and her husband, having fled Berlin via the Netherlands, were in southern France in 1942, apparently trying to make it to Spain. Unfortunately they were seized by the Vichy authorities and shipped from there to the Drancy camp, from which their fate was sealed : Auschwitz! The rest of the family managed to avoid those beasts, changed course, and were lucky to make it the following year across the mountains to Switzerland. We have no firsthand record of the horrors they must have endured after having lost two of their own and in constant fear as they moved from place to place to outrun the Nazis. Jeff