An American in Palestine 6

Mendes I. Cohen Tours the Holy Land Part VI: The Legacy of Mendes Cohen

Written by Dr. Deb Weiner. Originally published in Generations 2007-2008: Maryland and Israel.

Cohen’s final days in Palestine were a bit subdued. For some time, he had been tracking the course of the Plague and adjusting his route accordingly. As he had explained at the start of his Middle East trip, “The mortality of the Cholera is not so great as that of the Plague: with the latter, one half or more, who take it, generally die, while in the former not more than one in four.” The dreaded disease broke out in Jerusalem toward the end of his second stay there and he decided to keep “a rigid quarantine” until his departure.[i]

He did venture out to a town near Mt. Tabor, “where is held every Monday a large fair. I arrived at it when at its height. I suppose there must have been 800 Arabs at it. They come from all parts, from miles around.” Observing the lively conversations at this public gathering place, he commented, “I dare say their politics is talked over in the same style as they are at Washington tho’ not allowed so publicly.”[ii]

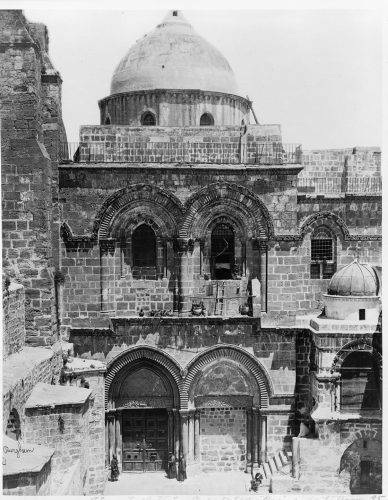

Cohen probably purchased some trinkets at this fair to add to the souvenirs he collected on his travels. His notes and letters describe a varied assortment of items acquired during the journey. “I have a bottle of water of the Jordan and one of the Dead Sea, with some other little etceteras picked up at Jerusalem,” he wrote in one letter. In another, “I am getting made a few Thephilin and Mazuzahs and perhaps may have a sapher made should I return this way from Egypt.” While some keepsakes had special meaning for him as a Jew, he also collected for others, including Christian acquaintances. During a second and more leisurely visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, he picked up “a fine long wax candle and a book of the service which I have in my mind to present to some of my friends whom I met at Paris and whom I am sure will appreciate its value from the circumstance of its having passed through the various stations within the church.”[iii]

But the items that Cohen gathered were far more than just the mementos of a tourist. Along the way he collected seriously and he collected well. The artifacts he purchased during his journey up the Nile River constitute the “first important American collection of Egyptian antiquities” and form the basis of the Johns Hopkins University Archaeological Collection, “one of the oldest and richest university collections of classical artifacts in the United States.”[iv] His notebook of detailed sketches and descriptions of the flora of Palestine somehow found its way onto a shelf in the Hebrew University, where it was later rediscovered and, according to Israeli botanists, appears to be the most complete record of 19th century flora of the land of Israel.[v] He also kept a study notebook featuring an alphabetical list of definitions and descriptions of the phenomena he came across. In entries such as “abraxas,” “crocodile,” “hand,” “kohl,” and “rings,” he carefully recorded the customs of the people he encountered as well as their natural surroundings.

Cohen’s letters and diary entries do not reveal him to be a particularly introspective person. It is interesting, then, that the study notebook begins with four long biblical quotes that, since he rarely quoted at length from the Bible in his journals, appear to have had special meaning for him. All are admonishments to the Israelites to not act like others, to remain a people apart. Three forbid the making of idols or graven images, “for I am the Lord your God” (Lev. 26.1). The fourth quote, from Leviticus 18.3, serves as a summation: “After the doings of the Land of Egypt wherein ye dwell, shall ye not do; and after the doings of the Land of Canaan, whither I bring you, shall ye not do; neither shall ye walk in their ordinances.”[vi]

Mendes I. Cohen returned to the United States in 1835 and though he had other occasion to travel abroad, remained thereafter a lifelong citizen of Baltimore. He served in the state legislature, became a director of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and was awarded the honorary title of Colonel because of his service at Fort McHenry. He took his place as a Jewish communal leader, serving as vice president of the Hebrew Benevolent Society for more than twenty years. In 1858 he presided over the meeting at which plans for the Hebrew Hospital of Baltimore were made. He also was a director of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum.[vii]

Upon his death in 1879 at age 83, newspaper obituaries recounted Cohen’s exploits both as Fort McHenry defender (he was the last survivor of his artillery company) and as world traveler. They emphasized as well Cohen’s religious commitments, noting his communal leadership and his penchant for private worship. Concluded the Baltimore Sun, “He was always a firm upholder of the faith of his fathers.”[viii]

The obituaries also assessed Cohen’s place in Baltimore society and did a good job of capturing his personality. “Col. Cohen was one of the oldest and most highly respected citizens of Baltimore,” stated the Evening Bulletin. He “frequently entertained his friends by describing scenes and incidents of his travels.” Although he was blind the last three years of his life, “he was almost daily on the streets, attended by a servant, and his tall and commanding figure could frequently be seen on North Charles and Baltimore streets, near the scenes of his early activity.” A man of action to the end.

~The End~

[i] Travel notes; unidentified newspaper article dated Smyrna, Nov 6, 1831 (see note 7); letter to Judith Cohen, October 2.

[ii] Letter to Judith Cohen, October 2.

[iii] Letter to brothers, March 28, 1832; letters to Judith Cohen, March 19 and 24.

If his first visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre made him feel claustrophobic, his second made him uncomfortable for other reasons. He arrived during a ceremony that featured priests parading with ritual objects, while pilgrims drew near to kiss the objects. The Turks, he wrote, “are always in attendance to preserve order . . . this they accomplish by using the whip-sticks which they used most liberally to the legs, heads, shoulders and backs of the pilgrims whose sole object” was to reach the priests, “who encouraged the people to approach at the expense of a good thrashing which they [don’t] mind receiving.” He concluded, “I remained about an hour witnessing such a scene—a disgrace to their religion.”

[iv] His nephew Mendes Cohen donated the collection to JHU after his uncle’s death. See neareast.jhu.edu/archaeo/Renovating%20the%20Archaeological%20Collection.pps; usepigraphy.brown.edu/epigraphic_holdings.html.

[v] Conversation with Israeli botanist Ofer Cohen, July 2008, Baltimore.

[vi] Study notebook, “1829-1833: Journeys of M.I. Cohen” Folder, Box 4.

[vii] “A Prominent Hebrew Dead,” Evening Bulletin, May 7, 1879; “The Late Mendes I. Cohen—Interesting Sketch of his Life—Reminiscences, &c.,” Baltimore Sun, May 8, 1879; two unidentified newspaper obituaries, “Mendes I. Cohen” Vertical File, Jewish Museum of Maryland.

[viii] Ibid.