An American in Palestine

Mendes I. Cohen Tours the Holy Land Part I: World Traveler

Written by Dr. Deb Weiner. Originally published in Generations 2007-2008: Maryland and Israel.

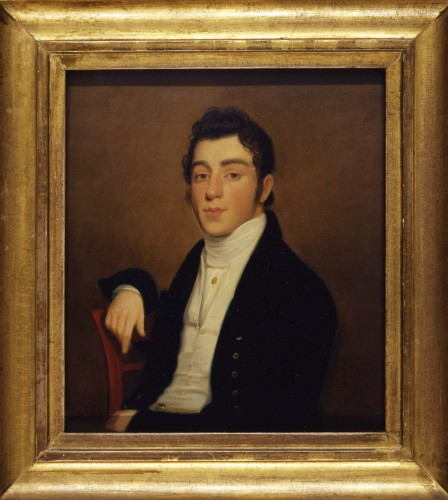

Ca. 1835-1840. Oil on cardboard, Artist unknown. Museum Department, Maryland Historical Society.

“Very few of the Jews in Jerusalem have shoes,” Mendes I. Cohen remarked in an 1832 letter to his mother. This tidbit is just one of the fascinating observations made by Cohen, 36-year-old son of a prominent Baltimore family, during his grand tour of Europe and the Middle East.

An intrepid traveler, proud American Jewish citizen, and lifelong Baltimorean, Cohen was one of the first Americans to explore the Holy Land. The letters he wrote back home to his mother and brothers provide a remarkable depiction of the early 19th century Middle East and an equally remarkable portrait of an American abroad.[i]

Cohen was well suited to the role of world traveler: brash and confident, he possessed an adventurous spirit and the financial means to go wherever his fancy took him. Whether visiting with English aristocrats or bedding down in Gaza in a “trough used to feed cattle,” he seemed unfazed by any circumstance. This was fortunate, because the array of challenges he confronted during his journey would have daunted even travelers of his own era. To the modern-day reader accustomed to guided tours, cruise ships, and credit cards, his exploits seem almost laughably difficult, an Indiana Jones-type series of ordeals. There were shipwrecks and sandstorms, war zones to travel through and the Plague to avoid. Fortunately he cut a physically imposing figure, which probably helped him in some difficult situations. According to his 1834 passport, he stood “six feet two and a half inches,” with “hazel eyes, dark hair, fair skin and common features.”[ii]

Tellingly, perhaps Cohen’s most uncomfortable moment came not when facing down a Bedouin sheik in the Sinai desert, or when people around him started dropping dead of cholera in Turkey—but in the Ashkenazi synagogue in Jerusalem, when he was called up to the bema “and forgot to say the Blessing.” After temporarily throwing his hosts into “apparent confusion,” he caught his error, said the blessing, and “all things went on right” after that.[iii]

The incident captures the essence of Mendes I. Cohen’s identity: he was American enough to forget the blessing, and Jewish enough to be deeply embarrassed by his faux pas. His strongly American and strongly Jewish proclivities both stemmed from his upbringing. Mendes was born in Richmond in 1796 to Israel Cohen, a Prussian immigrant, and his wife Judith, who came from England. His uncle Jacob I. Cohen, a Revolutionary War veteran, had co-owned Richmond’s largest Jewish business, which had employed Daniel Boone as a surveyor along the Ohio River. Mendes came to Baltimore with his widowed mother and six siblings in 1808. At age eighteen he was a defender of Fort McHenry against the British as a member of a local militia that included his brother Philip and friend Samuel Etting. Since the families of militiamen were responsible for feeding them, the boys received daily shipments of kosher food by cart during their stay at the fort (Samuel’s father, Solomon, had trained as a schochet). Although thoroughly assimilated into Baltimore society, the Etting and Cohen clans remained traditional Jews who kept kosher, held regular services, and fought for Jewish civic equality. The children received a thorough Jewish education.[iv]

After his stint at Fort McHenry, Mendes joined the family’s prominent banking and lottery firm, J. I. Cohen Jr. & Brothers, and for a time managed the firm’s New York branch. But as the fifth of six brothers, and unmarried at that, he had the freedom to do pretty much what he wanted with his life. And what he wanted, during his thirties, was to see the world.

Continue to Part II: The American Abroad

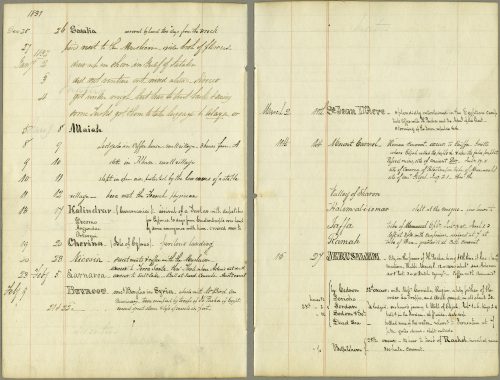

[i] Mendes I. Cohen’s letters and travel journals are part of the extensive Cohen Collection in the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore. The collection, MS 251, covers several generations of the family. His correspondence can be found in MS 251.3, Boxes 1 to 4. All letters cited in this article are from Box 2. The travel journal cited in this article is from Box 4, Folder “1829-1833: Journeys of M.I. Cohen.” The travel notes are from Box 2, Folder “1832 August 25-Sept 5.”

Mendes I. Cohen helped to found the Maryland Historical Society in 1844 and his nephew and namesake, civil engineer Mendes Cohen, was a longtime president of the Society.

[ii] Travel journal, September 16-18, 1832. The passport is in the Cohen Family Papers, American Jewish Historical Society, New York. The quoted description is from Ann Lynn Lipton’s “Anywhere, So Long As It Be Free: A Study of the Cohen Family of Richmond and Baltimore, 1773-1826” (MA thesis, College of William and Mary in Virginia, 1973), 36.

[iii] Letter to Judith Cohen, March 19, 1832.

[iv] “A Prominent Hebrew Dead,” Evening Bulletin, May 7, 1879; Aaron Baroway, “The Cohens of Maryland,” Maryland Historical Magazine (December 1923): 357-376; Albert J. Silverman, “They Ate Kosher at Fort McHenry,” Generations (December 1979): 2-9. For years, family patriarchs Solomon Etting and Jacob I. Cohen fought for the “Jew Bill,” which finally passed in 1826, changing Maryland law so that a Christian oath was no longer required to hold public office (Silverman, 7-8).

The Ettings and Cohens, having arrived in Baltimore early on, did not mix socially with the Bavarian Jewish immigrants who began to come in large numbers in the 1820s. But their Jewish identity was never in question. According to historian Moses Aberbach, the two families “preferred to maintain a private minyan” and they also had their own burial ground. They did join with fellow Jews in founding communal organizations such as the Hebrew Benevolent Society. “Cohen Family Settled in 1700s as Pioneers of Baltimore Jewry,” Baltimore Jewish Times, June 28, 1974.