Intern Weekly Response: DC Field Trip

Every week we’re asking our summer interns to share some thoughts and responses to various experiences and readings. This week we asked them to share about their recent field trip experience to the National Mall in Washington, DC. To read more posts from JMM interns, past and present, click here.

Turning Up the Volume on Indigenous Voices

~Intern Marisa

I’ve already written a little bit about our trip to DC in my blog post last week in which I discuss the Dragons in Art tour we took at the National Gallery of Art and the value of an interdisciplinary approach to programming.

Today though, I’d like to talk about what I saw at the National Museum of Natural History that I thought was really well done: how the museum gave a platform for indigenous voices. I saw this in two of their exhibits: Narwhals: Revealing an Arctic Legend and Objects of Wonder.

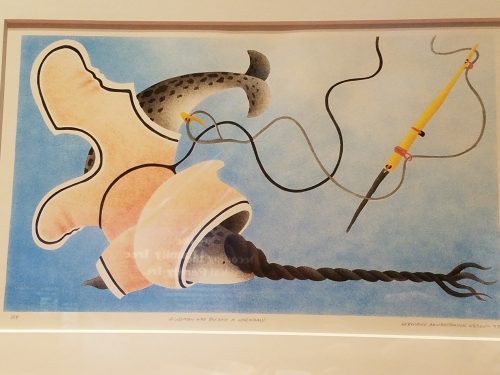

In the Narwhals exhibit, the National Museum of Natural History did a couple of different things to help highlight Inuit voices. First, they took an interdisciplinary approach to the exhibit, and displayed Inuit art and described legends that depict the cultural importance of the Narwhal.

Second, they explored the fascinating relationship between Inuit cultural knowledge and science, and how it is Inuit cultural knowledge that informs science, rather than the other way around. For instance, it has been culturally known, through experiences and stories passed down in the Inuit communities, that the narwhal’s tooth [which looks like a horn] can actually bend. The scientific community then put this to the test and confirmed this piece of cultural knowledge. The museum made sure time and time again in that exhibit to validate and display how Inuit cultural knowledge has helped science learn more about narwhals. Third, and most importantly, is that the museum worked directly with the Inuit communities in the creation of the exhibit. They had interviews and videos, art and stories, some of which was done for the express purpose of this exhibit; this allows the Inuit communities to shape their own narrative and share it with a larger audience who may not have heard their voices otherwise.

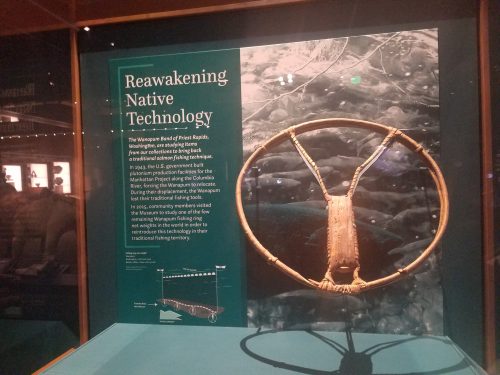

So, the Narwhals exhibit is a fantastic example of how to work with indigenous communities whose culture and technology are still intact and preserved, but how can the museum help communities that have lost that, for any number of reasons? In the exhibit, Objects of Wonder, the museum shows us one of the coolest collaborations. I should say first that the Objects of Wonder is a sort of exhibit of smaller exhibits, with an overarching goal of teaching visitors about the museum’s vast collection and how those items ended up at the museum. One of these small exhibits within the exhibit was on the fishing ring net weights of the Wanapum Band of Priest Rapids.

The community had lost this technology due to the creation of a United States government plutonium facility that “forc[ed] the Wanapum to relocate.” In 2015, members of this community traveled to the museum to study one of the only remaining examples of this technology with the goal of reverse engineering it and bringing this traditional practice back to their community. The collaboration between the Wanapum and the museum, which was discussed thoroughly in the display, not only highlights the plight of forced relocation of Native American populations, but also how cultural institutions can work with these communities to preserve and support their culture.

With these two exhibits, the Natural History Museum has given an opportunity for indigenous people to share their stories and have their voices heard and is setting the bar for how to do this in a respectful and engaging way.

IPOP and the Power of Interdisciplinary Exhibits

~Intern Cara

As someone coming from a humanities background, natural history and science museums have typically felt inaccessible to me. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History ‘s exhibit, Narwhal: Revealing an Arctic Legend, changed that for me. I feel like this exhibit has flipped the script on what a natural history exhibit can be and achieve. This exhibit could have very easily just focused on the anatomy and behavior of narwhals but instead took a more engaging interdisciplinary approach. The exhibit touches on all aspects of Narwhals from their relation to their environment, climate change, the role of narwhals in native cultures, narwhals in pop culture to the history and mythology of narwhals and other horned creatures.

I think this interdisciplinary approach is particularly powerful way of engaging visitors. In my museum studies courses we’ve discussed the Smithsonian’s IPOP model of visitor engagement. The model “identifies four key dimensions of experience – Ideas (conceptual, abstract thinking), People (emotional connections), Objects (visual language and aesthetics), and Physical experiences (somatic sensations). The model maintains that individuals are drawn to these four dimensions to different degrees.” Just as visitors are drawn to certain dimensions of experience (personally I find myself more drawn to objects and physical experiences), people are drawn towards certain disciplines based on their interests. Interdisciplinary exhibits like the Smithsonian’s narwhal exhibit successfully keep visitors engaged by combatting the monotony of single discipline exhibits and allowing visitors to follow their interests.

Do we see all the artifacts a museum has?

~Intern Alexia

Many museums have a permanent exhibit, meaning that every time you go visit it you are going to see the same artifacts or paintings. Sometimes these exhibits are slightly modified by changing a small quantity of the items. But, those that exhibit composes the entire collection the museum has? The answer to this question is often no. Big collections for many museums are a problem because of storage, conservation, and deciding what to showcase to the public. Museums acquire artifacts for their collections from donations, loans, and by buying them. Because of the large collection the museum may have, many of these artifacts the viewer never gets to see them.

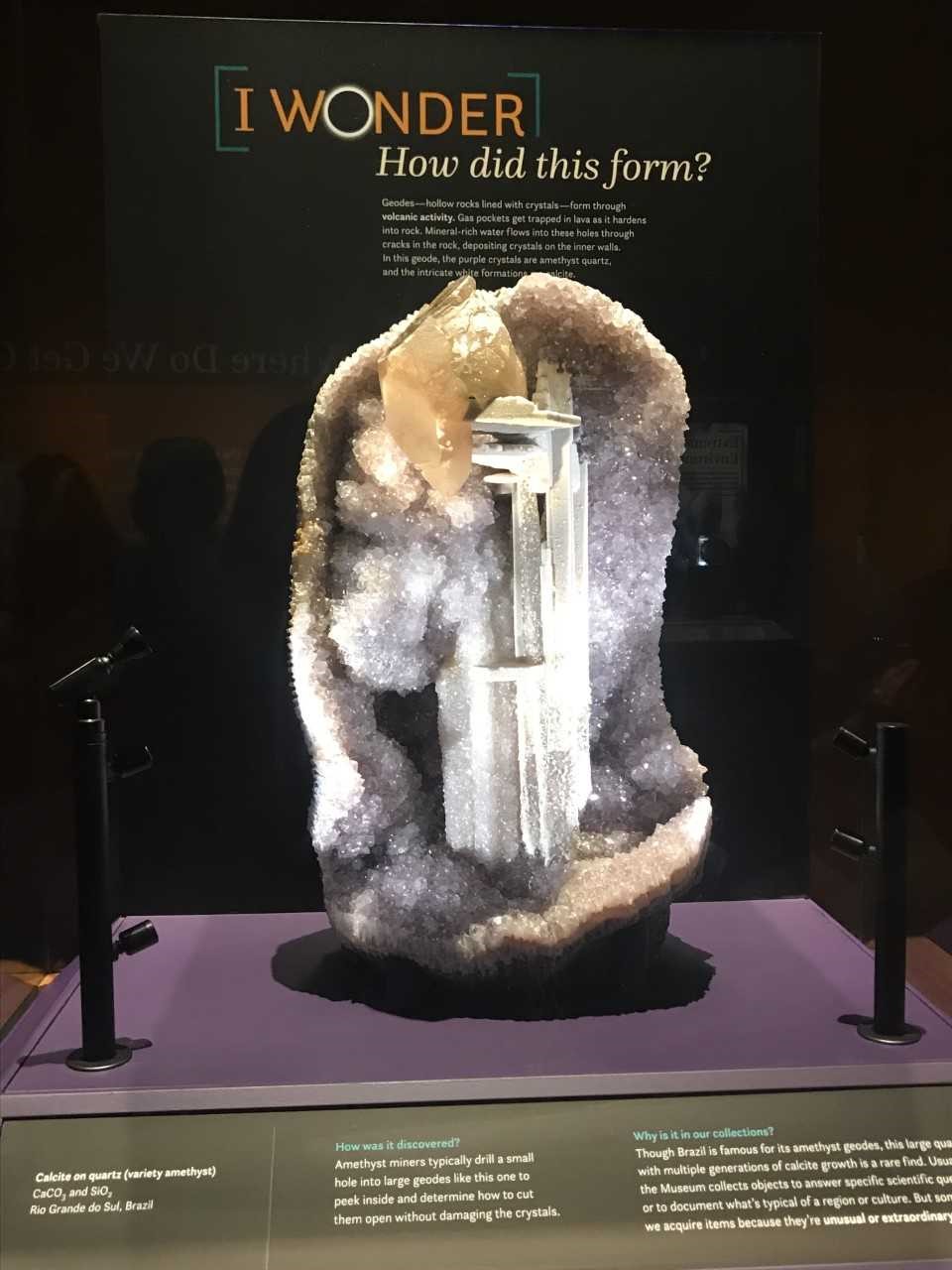

The topic of large collections and everything they entitle came to my mind while visiting the exhibit of Objects of Wonder in The National Museum of Natural History. This exhibit, which is located on the second floor of the museum encompasses a wide range of artifacts from different subjects such as migration, paleontology, and geology. Some artifacts from the exhibit include mammoth meat, butterflies, ceramics, fossils, and a Japanese samurai armor. But Objects of Wonders does more than just showcasing part of the large collection the Smithsonian has, it gives the audience a perspective they often do not get a chance to see.

When most people go to an exhibit they do not think how the artifacts that are shown got to the museum, why the curator chose them, or how do researchers or scientists use and study those artifacts. Objects of Wonder breaks that barrier between the museum and the visitor. Through the exhibit the visitor can read comments from the curator regarding how specific items joined museum’s collection. The visitor can also see how researchers use the different collections for their investigations.

The idea of creating an exhibit that encompasses a large range of topics to give the audience an overall idea of the collection a museum has is brilliant. By also having the curators notes throughout the exhibit the visitor has an inside of how they make an exhibit and their train of thought. The Natural History Museum was successful in creating an exhibit that flows well and tells the story of artifacts that do not necessarily have things in common.

Light and Sound: Immersion at the Smithsonian

~Intern Ash

When an interactive activity lights up, it draws us in. When we walk into a room with a different soundscape, the mood of the room changes. When light is shone on a specific area, it grabs our attention and sharpens our focus.

Light and sound are important aspects to consider when designing an immersive environment for visitors. After visiting the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History on an intern field trip a couple of weeks ago, I was captivated with the sound and light design in its exhibits. So, I wanted to talk about a few of the ways they used light and sound to immerse their visitors in their exhibits and environments.

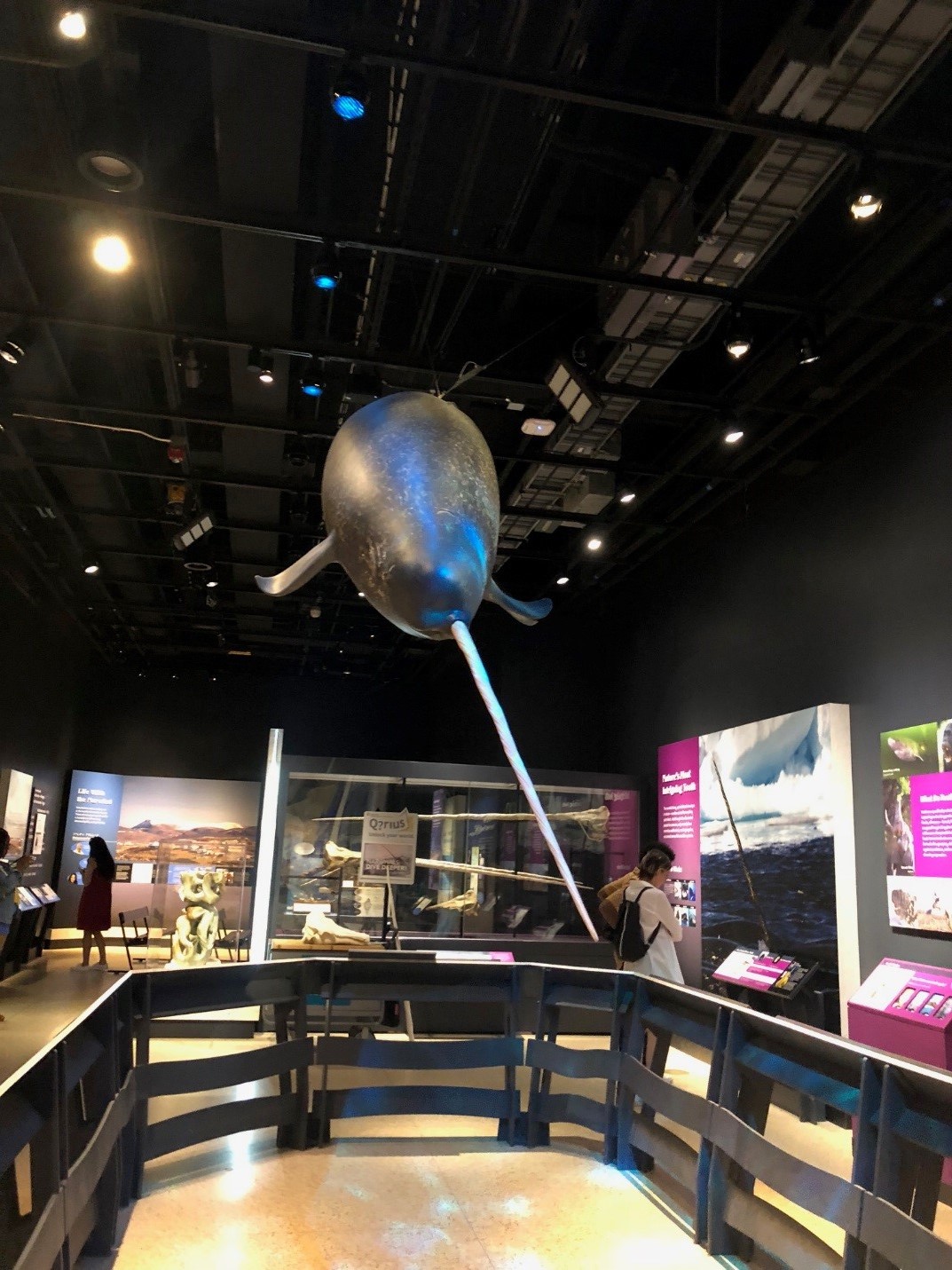

First, we headed to the Narwhal: Revealing An Arctic Legend exhibit. When we walked into this exhibit, seemingly abstract sounds filled the room. The best way to describe the soundscape was that it was like an interpretation of a mystical winter—slow creaking and shimmering notes, some haunting and deep, and others high-pitched and chattering. I was immediately enthralled with the sounds and was curious as to what they were. A panel in the exhibit described that they were “above-water sounds of Arctic birds and wind, and below-water sounds of narwhals vocalizing and ice moving and creaking.” The magical nature of these sounds fit well with the “mythical” legends that surround the Narwhal.

Along with the sound design, the lighting was sparse and kept to an ice and deep-water theme. Most of the lighting was a light, frosty blue, especially near the entrance. Around a hanging replica of a narwhal in the middle of the exhibit, there was shimmering blue light projected on the floor, mimicking how light shines through water. The walls and ceiling were painted black, absorbing the extra light and making the whole environment feel deep and mysterious, as if we were underwater. Overall, the sound and lighting design created the feeling of winter and the underwater deep as we walked throughout this exhibit.

Other than the Narwhal exhibit, there were a few other moments that I enjoyed throughout the museum because of their use of light and sound. In the David H. Koch Hall of Human Origins, there was a “cave” environment that had recreations of early human cave paintings. The lighting was dim and warm in this area, making the cave feel as if it was naturally and sparsely lit up. Low and haunting tones filled the space, and with the reading of a panel, I found out that the sounds were from playing a whistle artifact that was on display. This area and its haunting “music” created a sense of going back in time. It made me feel connected to early humans (my ancestors, of sorts) and their symbols.

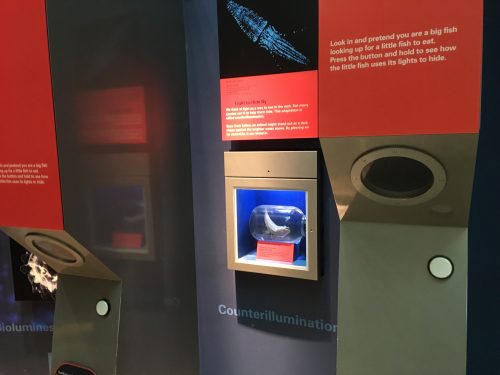

There were a lot of other areas of the museum where I enjoyed the lighting and sounds—a section on iridescent blues in the Objects of Wonder exhibit, an interactive about how fish use counterillumination to hide… But, seeing as how the museum has so many nooks and crannies, I don’t have the time to talk about them all. Overall, though, I can say that the parts of the museum that stuck with me the most were where these lights and sounds were used just right to transport me into a different world or time. In this way, the Smithsonian uses light and sound to its fullest. It combines them in the most captivating ways, forming enchanting environments and immersive spaces for visitors to explore.